The Palace of the Government, built from 1868 to 1873

In August 1887, Léon Caubert, a member of an official French delegation to China, made an overnight stop in Saigon to attend a grand ball hosted by the Governor General of Indochina. This translated excerpt from his 1891 book Souvenirs chinois (“Chinese Memories”) describes his very brief stay in the Cochinchina capital.

On 12 and 13 August 1887, we were lucky to cross the Gulf of Siam without heavy seas. Just a few months later, the unfortunate Japanese battleship Unebi was lost here, body and soul.

The Cap St-Jacques lighthouse

The heat had now become much more tolerable, and on the evening of 13 August, when at about 7pm we saw the lighthouse at Cap St-Jacques [Vũng Tàu], we were almost ready to accuse those geographers who describe Cochinchina as a hot country of exaggeration.

Following a brief report from the Cap St-Jacques semaphore office, which shares with an English telegraph company a hut on a wooded and tiger-infested outcrop, we saw a small steam boat arriving alongside the Natal. It was a launch belonging to a senior official from Saigon, who greeted the Deputy Special Envoy and welcomed him on behalf of Governor-General Filippini (20 June 1886-22 October 1887, died in office).

The Natal had to stop completely and was moored off the coast of Cap St-Jacques to await the high tide. The main thing I remember from that night was the violent discussion which ensued among my companions about the special breed of dog which inhabited the island of Phú Quốc. It concerned whether or not the hair of these animals grew in reverse, that is to say, whether their hair was not planted in the direction of their heads, instead of in the direction of the tail! This important question raised waves of bile and provoked such fury that it took nothing less than all-powerful intervention to restore calm!

Fishermen on the beach of Coconut Bay, Cap St-Jacques

The peak overlooking the lighthouse at Cap St-Jacques is separated from the mainland by a depression whose edges form a cove called the Baie des Cocotiers (Coconut Bay). This is the favourite seaside resort of Saigon, and one of our river pilots, M Arduzer, ran a little hotel there. If one stays at this resort, the sound of tigers may be heard all night, and of course, these animals won’t be afraid to pay you a nocturnal visit! But never fear, because at the Cap, one of the main occupations of the post of Annamese riflemen is to guard against these striped creatures.

Finally, at just the right time in the middle of the night, we began our journey up river towards Saigon. On the way, we passed two small gunboats descending the river with reinforcements for our troops, who had been sent to suppress an insurrection on the borders of Annam. Aboard one of these gunboats was a Phu (a type of native prefect) who, judging by the reputation he has earned carrying out various repressions, did not have a tender heart.

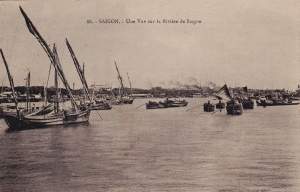

A view of the Saigon river

The next day we were awoken by a cannon shot, the only salute we received during our entire journey, signalling that we had arrived in Saigon.

Turning my head to the window without leaving my bed, I looked out at the banks of the river. It was very flat alongside the water, with mangroves and some bamboo. Nothing particularly exotic, except for some small Cochinchina oxen and some rather cranky wild buffalo.

I made my way quickly up onto the deck. The scene awaiting us was much more interesting than that which one sees on arrival in France, with large clumps of trees and tall buildings, mills and rice warehouses. We went ashore, walking slowly but agreeably; even for those people who had not suffered seasickness on the journey, it was a great physical rest not having to fight against the constant movement of the ship.

A steamer similar to ours, but smaller, was moored nearby. It belonged to the Tonkin and Annam authorities. As we walked a few hundred metres further, past the quai des Messageries, we made out two smart Landaus with four horses, a Daumont and a Victoria; the presence of these carriage crews indicated to us that the Governor General himself had come to meet the head of our mission.

The Maison Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes (1882)

Then indeed we saw M Filippini himself, along with his aide and his secretaries. After the usual exchange of pleasantries, we boarded our carriages, which took us at a trot to the Palace of the Government.

We crossed a magnificent single-arch iron bridge [the Maison Eiffel’s pont des Messageries maritimes], which was built over the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek] at the time when M Le Myre de Villers was Governor. We travelled along the quai du Commerce [Tôn Đức Thắng street], rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi street] and into the place de la Cathédrale, then took the wide boulevard Norodom [Lê Duẩn street] to the Palace. As we passed through the front gate, the Annamite sharpshooters on duty there presented arms in salute.

In all, our first impression was very favourable. In fact, it would have been excellent, had it not been for the heavy and humid atmosphere. But it’s precisely because of this difficult climate that we must admire all the more the enormous efforts which have been made and the results which have been obtained here.

Cathedral square at the top end of rue Catinat

Let’s not forget that our city is less than 30 years old; in another 30 years, if the improvements continue, if wise and timely administrative measures are taken, Saigon will be a great and beautiful city which will form a whole with its suburb of Chợ Lớn and may be home to more than one million people.

As in Singapore, the Chinese issue is very important here in Saigon, especially since most of the Chinese who have settled here in recent years are Cantonese, that is to say active and industrious traders. Certainly, we cannot afford to hand the reins of commerce to that population, as they would eventually reign as masters in our country; but we must hold them in respect and always treat them with fairness and scrupulous integrity. This is the safest way to ensure that these hard-working communities are harnessed to our ideas, and to make them, if not love, then at least appreciate, our domination.

Like all official buildings, the Palace of the Government is an imposing building, with a central pavilion, two wings and side pavilions. The central pavilion extends quite far back and forms the front of the great hall, which measures around 15m W x 50m L x 9-10m H. The other salons – the dining room, the atrium, the vestibules and the private apartments – are in keeping with the grandness of the building, but the number and dimensions of rooms is actually smaller than one first imagines, because on each floor of the Palace, the rooms are surrounded by a 4m wide verandah. The interior decor is modern, but not too heavy and quite tasteful.

A cormer of the Jardin de ville in Saigon

Lawns extend all around the palace and merge partially with those of the largest municipal park in Saigon, which bears the modest name Jardin de la ville (City Park) – although this does not prevent it from being a very nice place to walk, rich in high trees and intersected by wide avenues. We must not confuse the Jardin de la ville with the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, which is located at the other end of the city and is also well designed, well maintained and stocked with many interesting wild animals.

They were very busy at the Palace, making preparations for the ball to be held that evening in honour of the Governor. Gardeners pottered around bearing plants to adorn the rooms, stairs and verandahs; upholsterers removed covers from the furniture and nailed up bunting and strings of flags.

M Filippini had invited us to join him for dinner before the ball. Some of our party decided to return to the Natal first, in order to take an afternoon nap, but I preferred to make the most of my visit by taking a trip to Chơ Lớn on the steam tramway which operates a half-hourly service between Saigon and its Chinese suburb. The price of the trip was 12 cents per person (approximately 45 centimes, the piastre is thus worth 3.80 Francs).

French Indochina piastre de commerce coins, 1885

The Paris Mint manufactures, especially for French Indochina, silver coins in denominations of 1 piastre, 40 cents, 20 cents and 10 cents, and bronze coins in denominations of 1 and 2 cents. The effigy on these coins is that of the Great Seal of France [featuring Liberty personified as a seated Juno wearing a crown with seven arches], holding in his right hand a fasces, but with a relatively simple background.

It took 35 minutes to make the tram journey across a barren plain from Saigon to Chợ Lớn. The pace was fast enough, and I was told that in the evenings, many Saïgonnais take the tram in order to enjoy the cool breeze sitting next to the open carriage windows.

The price of horse-drawn carriages in Saigon is very moderate indeed: 30 cents for a single journey, 40 cents for an hour, 2 piastres for a day; they can also take you to Chợ Lớn, but on this day there was no question of making the journey by horse-drawn carriage, because nearly all of them had already been hired for the Governor General’s ball.

A Sài Gòn-Chợ Lớn ‘High Road’ tramway service arriving in Chợ Lớn

The city of Chợ Lớn has more than 80,000 inhabitants, most of them Chinese. It is clean, with wide and well surfaced streets and sidewalks where Annamite and Chinese shops mingle fraternally. They are open 24 hours a day and their counters, which contain no displays of goods, open directly onto the street; products for sale are stacked behind in semicircular rows.

Here we can see many weavers and manufacturers of cabinets made from camphor wood. Merchants also sell fabrics and items of hardware from all over the world, including England, Germany and America as well France.

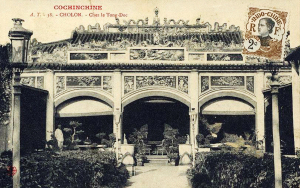

In Chợ Lớn, I was taken to visit the residence of the native prefect, the Phu of Cholon [“Tổng Đốc” Đỗ Hữu Phương, see Dinner with the “Tong Doc”] a well known personage in Cochinchina who is entirely familiar with our customs.

The family temple and “antiques museum” of the “Tổng Đốc” Đỗ Hữu Phương’s residence in Chợ Lớn

The interior of his residence is furnished partly in European and partly in Annamite style; his indigenous furniture, made from precious wood inlaid with mother of pearl, is very beautiful. I was told that some pieces had been sent to France and placed on display in our 1878 Exposition.

During my return journey to Saigon, I was struck by the colossal and imposing dimensions of the new Palais de justice (Central law court), which resembled a Greek temple.

The administrative services of the colony are centralised under the Direction of the Interior, which occupies several well-constructed buildings on rue Catinat, all of them perfectly adapted to the climate.

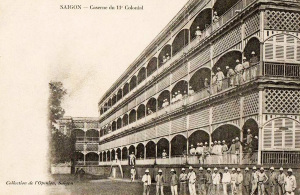

The Marine Infantry Barracks, located in the Citadel (though it is now only a citadel by name), are also very well ventilated; the walls of the barracks are open, allowing fresh air to circulate freely throughout their extent.

Part of the Marine Infantry Barracks in the former Citadel compound

Like most residences, all of Saigon’s public buildings have only one or two storeys, always surrounded by verandahs.

In recent years, a Château d’eau (water tower) with steam pumping apparatus was built to guarantee residents a plentiful supply of fresh water.

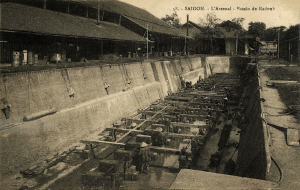

However two things are still lacking in Saigon – the first is adequate lighting and the second is a dry dock.

In 1887, Saigon was still lit by oil lamps, since attempts to install gas lighting had proved unsuccessful and the technology then available made it impossible to provide electric lighting. It seems that dynamos suffer almost as much as men from the humidity which prevails almost constantly here in Cochinchina, inducing oxidisation with surprising speed. However, it must be said that, although the city is still lit by oil, the quantity of Saigon’s street lights makes up for their quality.

As for the dry dock, this kind of installation is still rare everywhere, even in Europe. You may think, therefore, that it is even more rare in East Asia and Australasia. However, ships of more than 100m in length may already be refitted at dry dock facilities in Sydney, Australia, and at Kowloon docks in Hong Kong.

The dry dock which was eventually built in the Saigon Naval Arsenal

At the present time, our authorities in New Caledonia are lobbying to build a dry dock facility in Nouméa for the French fleet in the Pacific.

Here in Saigon, in 1881, instead of a dry dock, we installed a floating dock made from iron. However, this installation was short-lived: inaugurated during the course of August, it sank on 1 September 1881!

Yet, with an expenditure of about one million (not including machinery, pumps and sluices, of course), using modern methods of construction (the Monier reinforced concrete system, for example), we could very easily construct a large and perfectly waterproof basin. Surely it would be much more useful to build it here in Cochinchina, rather than in New Caledonia!

I had intended to head straight back to the Natal to get ready for the ball, but I suddenly remembered the recommendation made to me by a fellow traveller to change my French money to piastres during my visit in Cochinchina.

The original Banque de l’Indochine building on quai Belqique (now Võ Văn Kiệt)

Arriving in Saigon, travellers coming from Europe and continuing to China will certainly benefit by changing gold or European banknotes for piastres; but it’s important to demand Mexican piastres [the Indochina piastre was initially equivalent to the Mexican peso]. This is because the Mexican piastre is always worth less in Cochinchina than in the Chinese ports, and the difference in rate increases gradually as one moves northward. So, by changing French money for Mexican piastres in Saigon, you will get a better return later. An exception must be made, however, for Japan, where the piastre exchange rate is usually very low.

At 7.15pm we were sitting on the first floor verandah of the Palace of the Government. The street lights illuminating Norodom Boulevard stretched into the distance in four long lines and their perspective was very reminiscent of the Champs Élysées.

The dinner, served in French style, was as good as one could expect in Cochinchina, where fresh vegetables, in particular, still leave much be desired.

Another early view of the Palace of the Government

Since the advent of the civil governors, the tone of the Palace has declined significantly, but one cannot blame this decline of representation on the officials who have succeeded to this high office. Both Army and Navy officers benefit from a wide range of facilities and can subsist easily on a salary of 100,000 Francs, but such facilities are completely lacking for the civil servant, who costs us twice as much. From this point of view, many regret the replacement of admiral governors by civilian governors.

As we returned to the verandah for coffee, the guests began to arrive for the ball, the thousand lanterns of their carriages descending at full trot along boulevard de Norodom. It was just like the Place de la Concorde on summer nights, when carriage crews bring day trippers back from the Bois de Boulogne.

All the verandahs and all the rooms of the palace were illuminated. Through the bay windows of the atrium, we saw the great hall sparkling in understated detail, as bright as the grand ballroom of the Foreign Office in London, to which it also approximates in dimensions.

Guests attending a ball at the Palace of the Government

The official procession advanced into the great hall, and on the entrance of the Governor, the marine infantry band, located on a platform near the door, struck up the opening bars of the Marseillaise.

All around we saw many military uniforms and a plethora of pretty female costumes, and by the time the ball was in full swing, some 700 or 800 people were milling around the various salons of the palace.

Among them we saw the Phu of Chợ Lớn, very correctly dressed in a long black coat with an almost imperceptible red rosette, and wearing his badge of office, a white silk sash embroidered with gold. He was accompanied by his wife, Madame Prefect of Chợ Lớn, and his daughters; these ladies were surrounded by Europeans and natives who commented enthusiastically on the richness of their national costumes.

Gaming tables had been set up in several salons, and the card game Écarté was all the rage, with guests pitting piastres against Bank of Indochina notes in a frenzied dance.

The Palais de justice

Under the verandahs roamed groups of Annamite scholars and indigenous performers; they stopped occasionally to roll cigarettes at tables loaded with mountains of tobacco and piles of cigars, or to sample the food from the well-stocked buffet tables.

It was past 2am when we finally returned to the Natal in a carriage which a councillor had kindly placed at our disposal.

On the way back, the deep blue of the night sky was of unparalleled transparency; the moonlight reflected off the dusty roads and illuminated the colonnades of the Palais de Justice so vividly that the building appeared to be made of marble – a true Parthenon, which contrasted sharply with the surrounding clutter of dilapidated huts and pagodas with fantastic roofs.

As we approached the quayside, we heard the familiar drone of the mosquitoes, and so we went without lights into our cabins, so as not to attract those nasty insects. With this precaution, they left us almost alone.

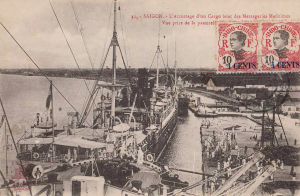

Unloading cargo from a ship at the quai des Messageries maritimes

A few hours later we were awoken by the last unloading of luggage from the Natal.

As I ascended onto the deck, the first person I met was our friend de Clamart, who was leaving us to go to Hà Nội.

“Did you find a good hotel last night?” I asked him. “Yes,” he replied, “They advised me that I should choose ‘the Hôtel Laval for sleeping, the Hôtel de l’Univers (Ollivier) for eating.’ But I must leave you now, because I have to go and make sure they transfer my furniture carefully.”

Just at that moment, a huge crate was hoisted precariously into the air by crane. “That crate contains my wardrobe,” said my companion, “I must go down to the quayside to receive it!”

De Clamart had hardly completed that sentence, when the crate became detached from the crane and fell heavily onto the deck of the ship with a terrible crash of breaking glass and splintering wood. It was painful to see the desperation of its owner, who had turned around just in time to witness this disaster. “I had a premonition that this might happen,” he muttered with a sorry air. “Bah!” replied one phlegmatic witness, “There’s no need to complain – the company will pay! Console yourself!” And indeed, this comment seemed to comfort my stricken friend.

Shortly before high tide, the Natal raised anchor and began its journey back down the Saigon River.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.