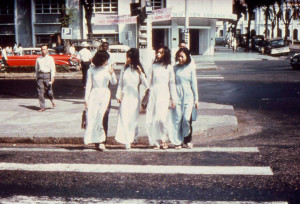

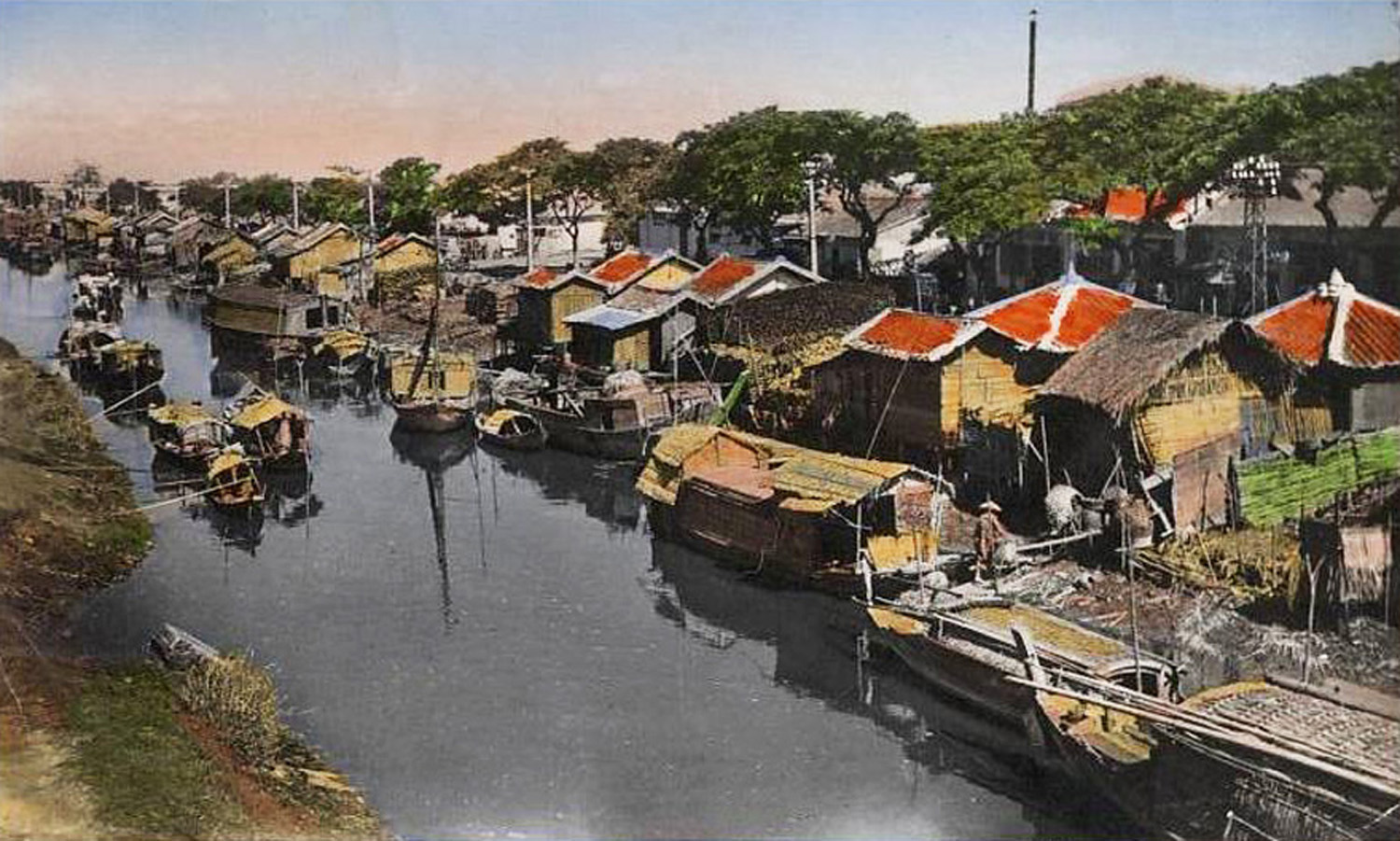

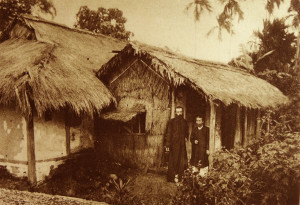

Planté, Cochinchine: Vers Cholon, le matin (undated)

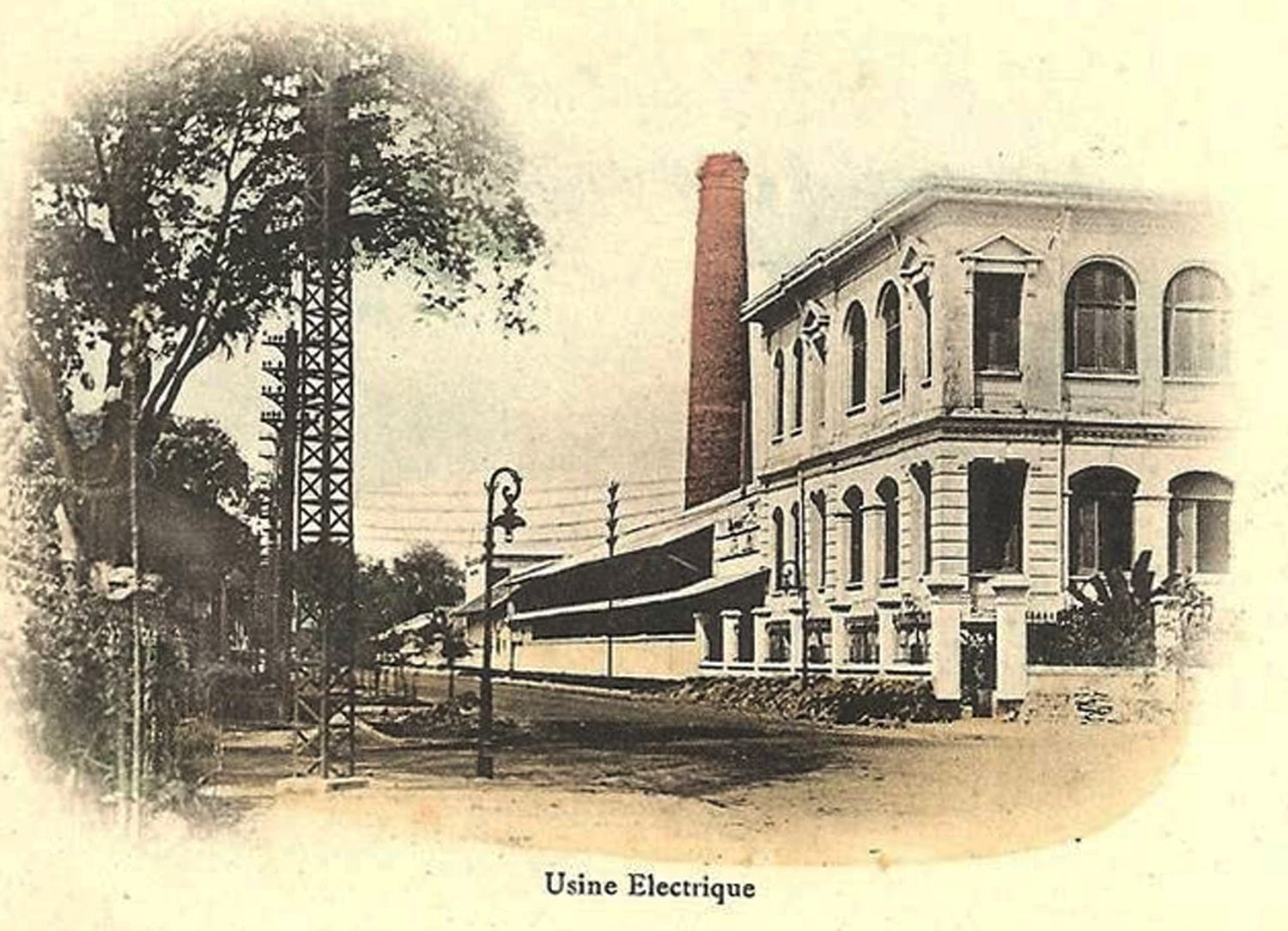

Published in 1889 by the Colonies Administration of the French Naval Ministry, Les colonies françaises: notices illustrées by Louis Henrique contains detailed information on early colonial Saigon. This excerpt describes the historical background to the establishment of French Cochinchina.

CONQUEST BY ANNAM. Lower Cochinchina was once part of the Khmer kingdom known as Cambodia; it was annexed in 1658 by Annam, and its ancient history is so intertwined with that of the Annamite kingdom, that only from 1859, the epoque in which it fell into our possession, did it have its own particular history. Nevertheless, it is useful to say a few words about the policy followed by the court of Hue to establish its domination over these provinces.

It is interesting that, from the 17th century, Annam proceeded just as France would do two centuries later: the work of conquest was begun at the river mouths, and continued with the annexation of the tributaries of the Mekong.

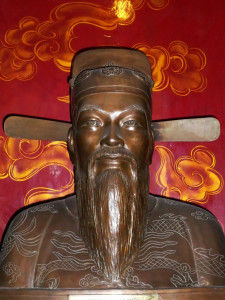

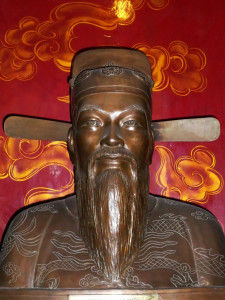

Nguyễn dynasty mandarin Trịnh Hoài Đức (1765-1825)

The mandarin Trinh-Hoai-Duc, writing in 1830, has left us the story of this conquest. Having little confidence in the submission of the Chinese colony and obedience of the Cambodian population, the Annamite government formed an administration recruited entirely from among the literati of Hue; then it ordered that vagrants and other vagabonds be picked up and transported to the new provinces.

Arable lands were carefully surveyed and registered, and properties were assigned to each settler; it was stated, moreover, that the Chinese would be fully assimilated with the Annamites.

This first wave of colonisation spread only through the three eastern provinces; it was only in 1720 that the Annamites seized the other three.

In 1800, new efforts were made to complete the colonisation, which had been halted by the revolt of the Tay-Son, the struggle for the establishment of the Nguyen dynasty, the uprisings in Cambodia and the war with Siam. The results that we have seen, and the resistance that we have had to overcome, are the best praise we can give the organising genius of the Annamite sovereign, Gia-Long.

In order to bring order to a population recruited from the slums and mixed with hostile elements, the following measures were decided: each settler was entitled to take as much land as he could cultivate; the mandarins then declared him the owner of the land which he fertilised; tax was proportionate to the products harvested and could be paid either in cash or in kind, at the choice of the settler; the Annamite Code [Vietnamese law] was applied in all its parts; and the calendar and the measures of the Chinese were also imposed. These institutions have so penetrated the usages of the people that they still exist today, alongside ours (see volumes on Annam and Tonkin).

A late 19th century French missionary’s residence near Huế

EARLY RELATIONS WITH FRANCE. If the conquest of Cochinchina by French arms dates back only 30 years, a great deal of time has passed since our missionaries first sought to bring European civilisation to these lands. According to M Louvet, the first French missionary to visit the Mekong Delta was Father Georges de La Mothe of the Order of St Dominic; he arrived in these regions in 1585, accompanied by Father Fonseca, a Portuguese national. They were very well received by the king of Cambodia, then ruler of the whole of Cochinchina; however, unfortunately for them, he conducted them to his capital. Soon after, the Siamese invaded the country. Father Fonseca was murdered in the church where he was celebrating mass; Father La Mothe, more happily, was able to flee aboard a Spanish ship, but he was covered with wounds and died before reaching Malacca.

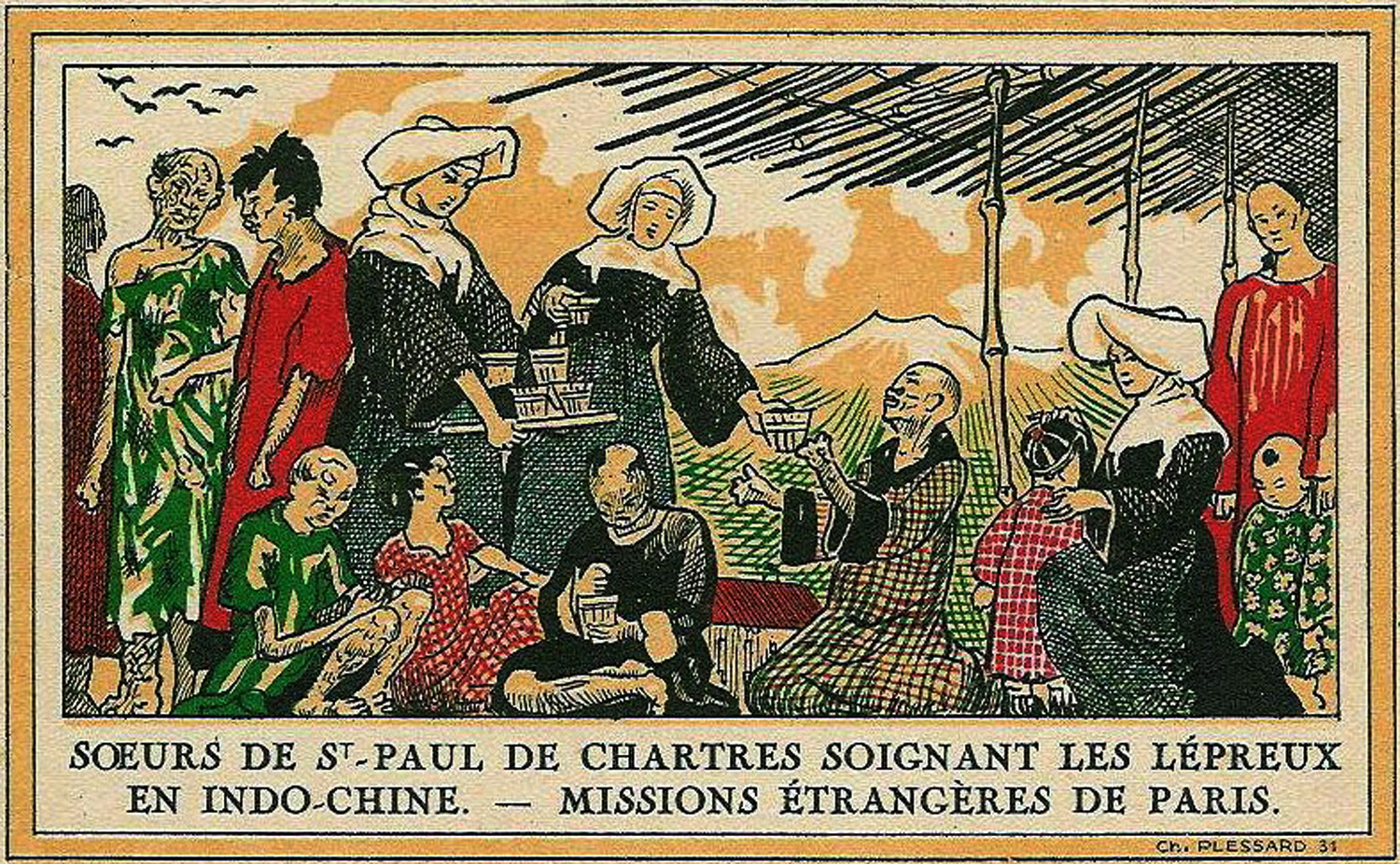

Later, the missionaries had to struggle, not only against the persecution of pagans, but also against the jealousy of other missionaries, including the Portuguese, who, all too often forgetting the principles of Christian charity, staked everything to promote the political and commercial interests of their nation. It was this hostility which led to the creation of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, the history of which is both curious and interesting in all respects.

However, the efforts of the Portuguese were at first crowned with great success; in Lower Cochinchina, in Cambodia and throughout Annam, as in the islands of Malaya, Christianity was known only as the “religion of the Portuguese.” If this state of affairs has now changed, it is due to the energy and perseverance of a French prelate who holds a special place in the history of both Annam in general and French Cochinchina in particular.

Portrait of Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau de Béhaine (1741-1798) in France, 1787, by Maupérin (Paris Foreign Missions Society)

THE BISHOP OF ADRAN. Pigneau de Béhaine (for this is the name of the man that we must keep in our memory) was born in 1741 near Laon, into a rich family, influential, distinguished by its alliances. Although he could have aspired to the great offices of state, he had but one desire, one ambition – to impart the word of Christ and spread the Christian faith in the most remote regions of the Far East. Barely 24 years old, he arrived at Cam-Cao, now Ha-Tien, which then belonged to the kingdom of Siam. His mission was troubled by war and persecution; the Catholics of Ha-Tien had to take refuge in Pondicherry. As a reward for his apostolic zeal, he was consecrated in Madras as the Bishop of Adran, a title which he carried for a quarter of a century.

Returning to Cam-Cao at a time when the whole of Indo-China was ravaged by bloody wars, he went to establish his residence at the place where today the city of Saigon is located.

At this time, Nguyen-Anh, who later became emperor of Annam under the name Gia-Long, was still struggling with alternate successes and setbacks. Pigneau de Béhaine had occasion to render important services to this prince, who was very popular in Cochinchina and had the good fortune to avoid the pursuits of his enemies, at the moment when his star seemed to have abandoned him. As a result, Nguyen-Anh conceived a friendship for the prelate which was as profound as it was durable.

One day of trouble, he requested the bishop to go and ask for the help of France, entrusting him with the care of his son in order that he could take him to the court of King Louis XVI. Pigneau de Béhaine left Indo-China with a heavy heart, as the most serious events were taking place here. He believed, however, that it would be enough to go to Pondicherry, where the young prince could complete his education. After waiting in vain for several years for a response to the request he had made to Versailles, the valiant bishop decided to make the trip to France to plead in person the cause of the heroic monarch, with the help of whom French influence in Indo-China could be established in a sustainable manner.

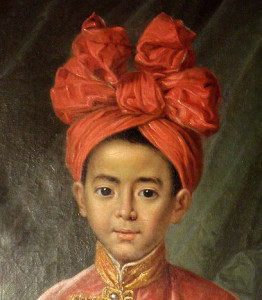

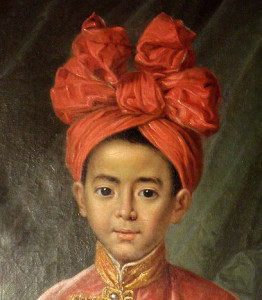

Portrait of crown prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh in France, 1787, by Maupérin (Paris Foreign Missions Society)

It was only in 1787 that the Bishop of Adran arrived in Paris. The events of the revolution were already getting under way, and at first it seemed that no-one would pay any attention to what was happening in the Far East. But Prince Canh-Dzue was pretty boy; he spoke French with a great deal of charm, and it was with special grace that he wore his national costume, which, along with his hairstyle, resembled that of our women.

The ladies of the court went crazy about him; according to the custom of that time, they adopted a new fashion in honour of the hero of the day, and for a while we lived with nothing but hairstyles à la Chinoise.

THE TREATY OF 1787. Louis XVI could not remain indifferent to the pleas of this attractive young man of royal race, who gave him the assurances of absolute devotion. On 28 November 1787, at Versailles, de Vergenneset de Montmorin signed a treaty of alliance, offensive and defensive, in which “a squadron of 20 French warships, five European regiments and two regiments of colonial troops” would be placed under the command of the king of Cochinchina. Moreover King Louis XVI pledged “to provide, in a few months, the sum of one million dollars (sic) with 500,000 in cash, the rest in saltpetre, cannons, muskets and other military arms.”

For his part, the king of Cochinchina was committed, among other things, “to assign, in perpetuity, the harbour and the territory of Han-Lan (bay of Tourane and peninsula), and the islands adjacent to Fai-Fo [Hội An], in the south, and to Haï-Wen, in the north.” All religious views were declared free.

As in the previous expedition of the Count de Maudave to Madagascar (see the notice on Madagascar), the French government entrusted the governor of French India with responsibility for meeting the commitments it had made, and once again, these commitments were not met. The Bishop of Adran invoked the formal orders of the king, but the Governor, Count de Conway, opposed the demands.

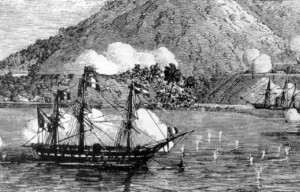

Rigault de Genouilly’s flagship the Ville de Paris in 1853 (engraving by Lebreton)

Unable to get anything from the governor, the bishop spoke directly to the settlers in Pondicherry, making them understand that it was in their interests to extend French influence in Indo-China and appealing to their patriotism so that the signature of the king of France was not ignored.

Pigneau was energetic and persevering, and his word was finally heard. In 1790, he arrived in Saigon with two ships loaded with weapons and ammunition, crewed by a team of active and dedicated officers, who proceeded to reorganise the Annamite army and fleet, and to fortify Hue, Saigon, My-Tho and several other places.

These officers were:

● J B Chaigneau, known to the Annamites under the names Nguyen-Van-Tang and Chu-Tau-Long (Commander Long); he commanded the Dragon volant.

● De Forçant, who was called Nguyen-Van-Chan and Chu-Tau-Phung (Commander Phung); he commanded the Aigle. He died in 1809.

● Philippe Vannier or Le-Van-Lang; he successively commanded the ships Bong-Thua and Dong-Nai, and then the Phénix.

These officers were successively joined by several other intrepid companions:

● Jean-Marie Dayot, head of a naval division of two Annamite ships, the Dong-Nai and the Prince de Cochinchine.

● Victor Ollivier (Ong-Tin), engineer officer in charge of the organisation of infantry, artillery and fortifications. He died on 22 March 1799 in Malacca, where he had been sent by Gia-Long for health reasons.

King Gia Long (reigned 1802-1820), born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh

● Théodore Le Brun, fortifications engineer.

● Lauront Barizy, lieutenant-colonel.

● Julien Girard de l’Isle-Sellé, captain.

● J M Despiaux, physician to King Gia-Long.

● Louis Guillon, lieutenant.

● Jean Guilloux, lieutenant.

(from Pétrus Ký, Histoire Annamite)

The events which occurred in France at that time completely diverted attention away from Cochinchina, where Gia-Long definitively established his power. Indisputably displacing the Le dynasty, he became actively engaged in public works, changes in legislation and the administrative organisation of Annam; His work can be compared to that of the greatest European monarchs.

For the remainder of the bishop of Adran’s life, Gia-Long lavished on him evidence of a lively and sincere friendship. When the bishop died on 9 October 1798, the king sent a beautiful coffin and rich silk fabrics in which to wrap the body. For two whole months, the coffin remained exposed for public veneration in the episcopal residence, which was located not far from the spot where the gunpowder magazine now stands.

The king himself presided at the funeral ceremony, which took place amidst great pomp on 16 December 1798.

The coffin, wrapped in beautiful silk fabric, was placed on a stretcher carried by 80 men and covered with a canopy embroidered with gold. The guard of honour was provided by the entire king’s guard, comprising more than 12,000 men. Overall, the procession included 40,000 people and 120 elephants armed for war and decorated with lavish ornaments. When they arrived at the place which the bishop had chosen for his burial, the king himself delivered the funeral oration.

The Mausoleum of Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran in Saigon (demolished in 1983)

A magnificent mausoleum was erected to his memory, entrusted to a royal guard of 30 men which was to be maintained in perpetuity.

The tomb of the bishop of Adran still exists today, and since we took possession of this land, it has been declared a historic monument.

VIOLATION OF THE PROVISIONS OF THE TREATY. During his reign, Gia-Long had been the protector and friend of Europeans. However, he was alarmed by the progress of the English in India, and before he died in 1820, he recommended actions against the Europeans to his son and successor Minh-Mang.

These actions were followed only too well. In 1824, the French, old friends of Gia-Long, were expelled. In the following year, Minh-Mang refused to receive the captain of the Bougainville. Then in 1847, during the reign of Thieu-Tri, the frigate Gloire captained by Lapierre, and the corvette Victorieuse under the command of Rigault de Genouilly, destroyed five Annamite ships in the Bay of Tourane, which had intended to attack them.

During the reign of Tu-Duc, persecution against the missionaries was intensified. In 1851, the French missionaries Schœffler and Bonnard were massacred on the king’s orders. In 1852, France lodged a formal complaint, but this was ignored, and in response, the corvette Catinat destroyed one of the forts of Tourane.

In 1857, following the arrest and execution of the Spanish bishop Diaz in Tonkin, France and Spain came to an agreement to obtain redress for the violence committed against their nationals and against the Christians of Annam, which at that time were estimated to number over 600,000.

Admiral Pierre-Louis-Charles Rigault de Genouilly (1807-1873)

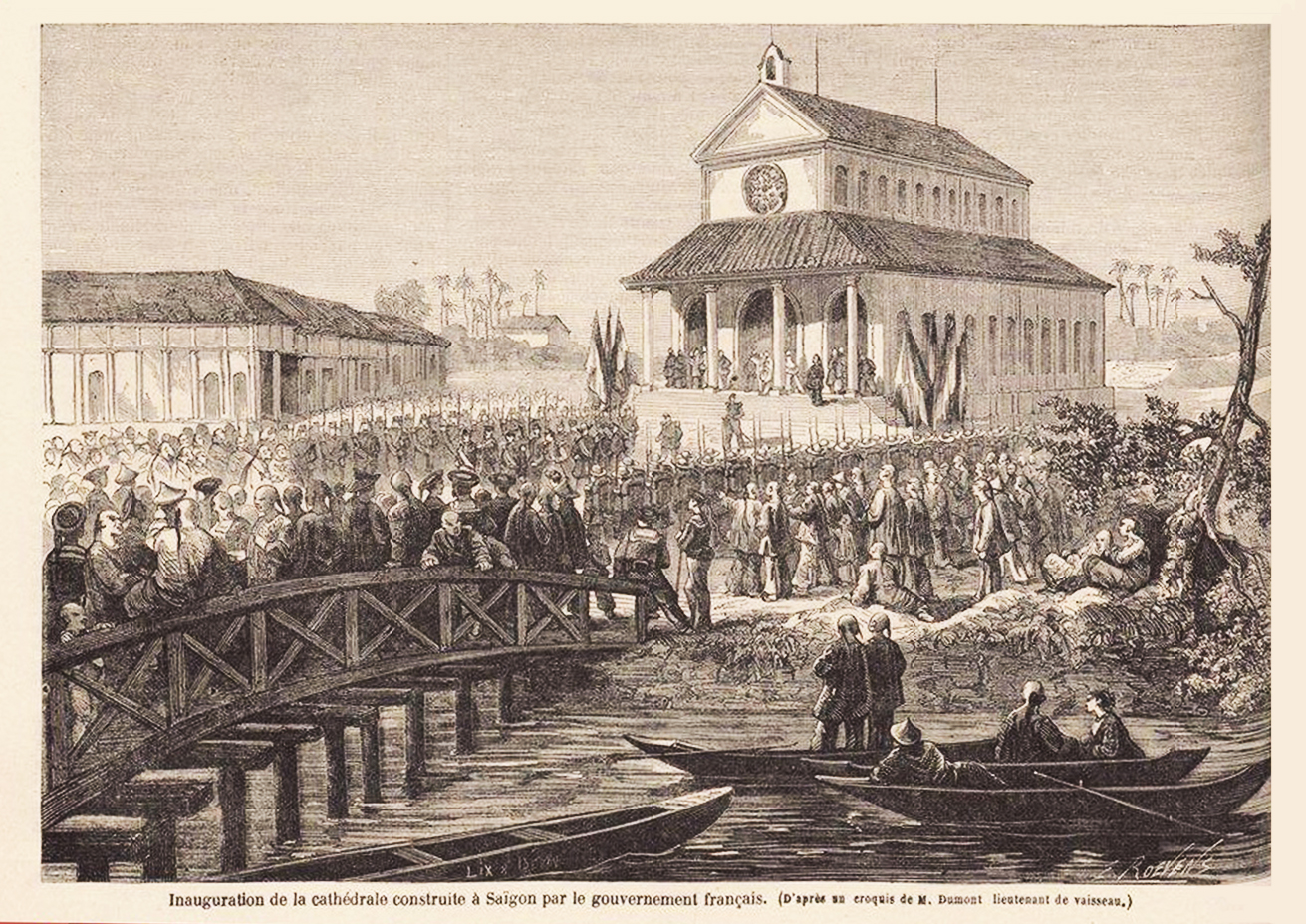

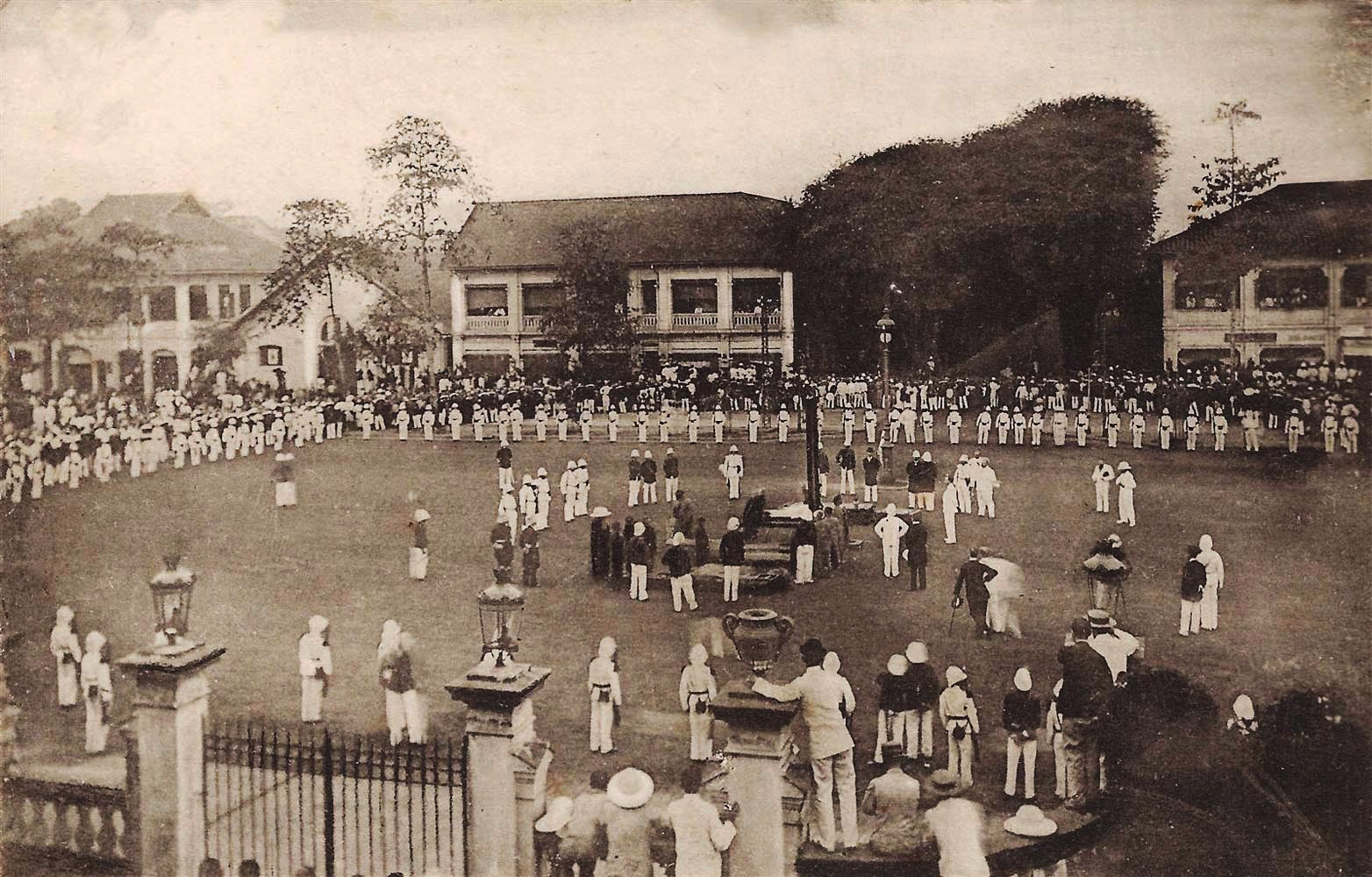

EXPEDITION OF 1858. On 31 August 1858, a Franco-Spanish expedition commanded by Admiral Rigault de Genouilly and the Spanish Colonel Langerote arrived in Tourane [Đà Nẵng], took the forts and settled on the peninsula which forms the boundary to the harbour entrance. They held it despite Annamite efforts to chase them away.

The bishop of Annam, Monsignor Pellerin, urged the admiral to march on Hue, but our ships could not enter the river because of the obstructions placed there by the Annamites, and the disease which was then wreaking havoc amongst the expeditionary force. For these reasons, the admiral decided to strike a blow elsewhere.

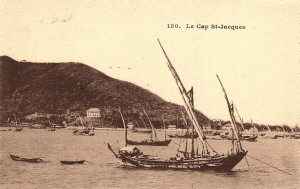

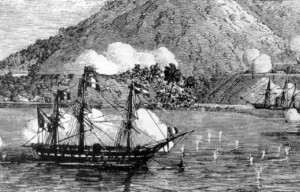

On 2 February 1859, leaving the captain of the Toyon in Tourane, Rigault de Genouilly left this port at the head of a naval division and headed for Saigon. On the morning of 10 February, the two forts which defended the inner anchorage of Cap Saint-Jacques [Vũng Tàu] were destroyed. On 11 February, the squadron sailed up the Dong-Nai river, setting Can-Gio Fort on fire.

From 11-15 February, they disabled and subsequently destroyed the forts of Ong-Gia, Cha-La, Tay-Ray and Tang-Ki. On the evening of 15 February, they arrived in Saigon.

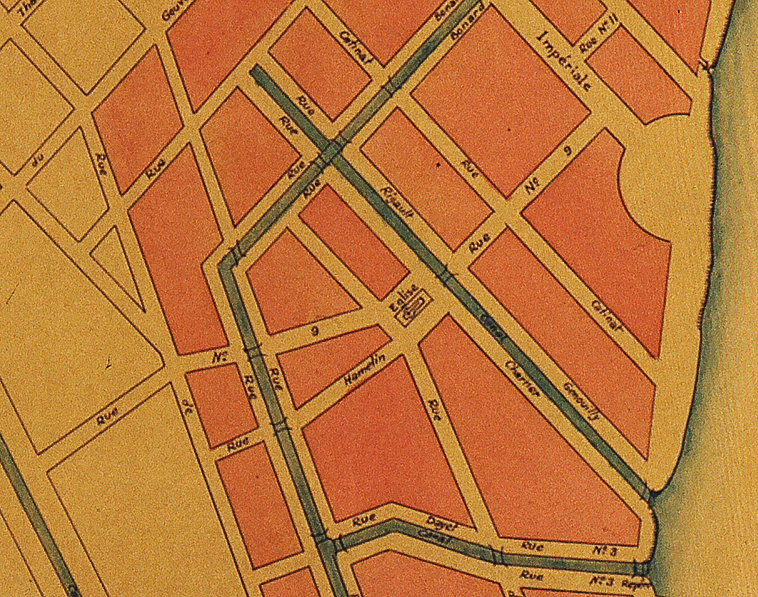

CAPTURE OF SAIGON. Saigon was defended in the south by two forts built in the European style and in the north by a large citadel. Hardly had our squadron come into sight when the guns of the two southern forts opened fire. One fort was immediately silenced; the other, much better armed, could not be attacked until the following day. The one on the right bank was dismantled, while the one on the left bank (the Fort du Sud) was occupied to serve as a support installation for our transport and convoy ships.

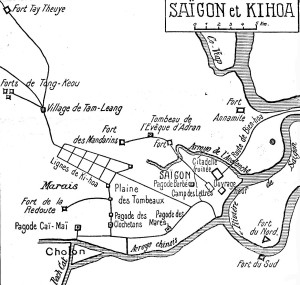

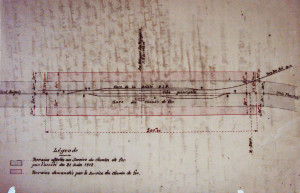

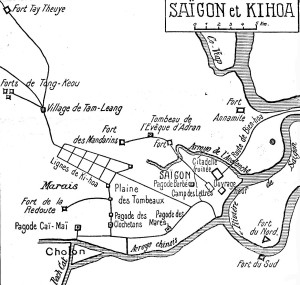

A Saigon port map of 1863, showing the location of the Citadel

All that remained was the Citadel, a square shaped structure situated 800m from the forts. Its walls, which had a combined length of 478m, were surrounded by a wide and deep moat. Four large bastions defended the corners, and in the centre of each of the four walls was a gate which opened onto a stone bridge. The citadel was surrounded on all sides by woods, gardens and houses. At 1700 hours, following a reconnaissance made by commander Jauréguiberry, the squadron commenced its bombardment. At first, the occupants of the Citadel responded vigorously, but their fire soon slowed as a result of the accuracy of our shooting. The assault columns landed and took up positions in the surrounding houses. The fire of our sharpshooters was successful; struck from all directions, the enemy abandoned its guns. Our troops, headed by marine infantry sergeant Henri de Pallières, rushed to the assault.

Capturing Saigon made us masters of considerable materiel: 200 guns of iron or bronze; a corvette; eight war junks still under construction; 20,000 swords, spears, rifles and pistols; 85,000kg of gunpowder; huge quantities of cartridges, rockets, projectiles, pig lead, and other military equipment; enough rice to feed 7,000-8,000 men for a year; and a box containing 130,000 francs.

CONQUEST OF THE PROVINCES. In April and May 1859, Admiral Rigault de Genouilly continued his offensive operations. Returning to Tourane, he defeated the Annamites, and, on 7-8 May, he took the entrenched camp of Kien-San, which commanded the road to Hue.

However, the war in Italy, and later the China expedition, obliged us momentarily to abandon the conquest of Lower Cochinchina. On 1 November 1859, Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, recalled to France at his own request, was replaced by Admiral Page.

French ships in Tourane harbour, 1858

Our low numbers forced us to evacuate Tourane on 23 March 1860, so that we could concentrate on Saigon.

The court of Hue announced our evacuation of Tourane as a brilliant victory. The king issued a proclamation announcing to his people that he had driven out the barbarians. “They are gone,” he said, “these terrible, greedy creatures who have no inspiration other than doing evil, no purpose other than making filthy lucre. They have disappeared, these pirates who feed on human flesh and make clothes from the skin of the poor unfortunates they have eaten! Put to flight by our soldiers, they are shamefully saved from our retribution!”

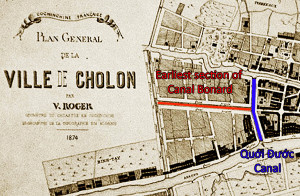

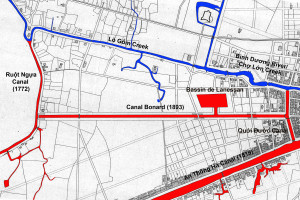

Soon after this, Admiral Page was sent to China, leaving in Saigon a garrison of 800 men, including 200 Spaniards and a small fleet of two corvettes and four smaller sailing ships. The command was given to Captain d’Ariès, with the Spanish Colonel Palanca Guttierez as his deputy. During this period, Commander d’Ariès consolidated his control over Saigon and Cholon, connecting the two cities with a series of rural fortifications, each protected by 30 rifles and 80 howitzers.

Meanwhile, the enemy was not idle. Taking advantage of our numerical weakness, the Annamites built the defensive lines of Ky-Hoa, 4 kilometres north of Saigon. In this way, they dominated the roads to Cambodia, My-Tho, Hue and the upper reaches of the Dong-Nai river. They blocked our little garrison to the point where it remained for almost six months without news from outside. The Annamites even launched a direct attack on our garrison on the night of 3-4 July. They were driven back and did not dare to attack us again, but they repeatedly approached our positions.

A map of the Battle of Ky-Hoa, 1861

The end of the China campaign allowed us to resume the hostilities with vigour. On 6 February 1861, Admiral Charner arrived with a naval division and an expeditionary force of 3,000 to 4,000 men, including 230 Spaniards and an indigenous company formed in Tourane, composed of Christians who had embraced our cause.

The first objective of admiral Charner was the removal of the lines of Ky-Hoa, an operation that he undertook with great success on 25 February. The Annamites took flight; they had lost over 1,000 men, killed or wounded. Our losses were also severe; 225 of our men had been put out of action, including 12 killed. Among these were Commanders Foucault and Rodellec-Duporzic, Ensign Berger, and Midshipmen Noël and Frostin. Lieutenant-Colonel Testard of the Marine Infantry was hit in the head and shoulder. Ensign Johaneau-Lareynière and the Spaniards Jean Lavizeruz and Barnabé Fovella died as a result of their injuries.

When Lareynière fell, several friends came to offer him help. His response was heroic, worthy of that of Walhubert at Austerlitz: “Go back to your station,” he said to one of them, “and write to my family telling them that I died bravely.” In Sparta or Rome, these words would have been carved on a monument. France, oblivious of his glories, continues to ignore these words of its unknown hero.

The destruction of the lines of Ky-Hoa was followed by the conquest of Tong-Keou, Hoc-Mon, Brach-Tra and Trang-Bang. Meanwhile, Admiral Page ascended the Dong-Nai river, destroyed the forts and landing stages, and dispersed 15,000 men who were defending its course. Saigon was delivered, and the province of Gia-Dinh conquered. “The expeditionary army, in the space of a fortnight, had fought five battles, undertaken 12 reconnaissances, and marched under a brazen sky, despite the deadly climate and the fact that biscuit rations and water were often spoiled and our soldiers were kept awake every night by the poisonous bites of mosquitoes and fire ants.” (L Pallu)

Admiral Louis-Adolphe Bonard (1805-1867)

Taking the arroyo de la Poste, which leads from My-Tho into Cambodia, cost the life of Captain Bourdais. After the enemy had withdrawn, Admiral Page’s fleet arrived at My-Tho on 12 April. The rainy season started and our troops were sent to their quarters.

On 29 November, Admiral Charner left for France, leaving the command to Admiral Bonard. In the following month, the latter seized Bien-Hoa and Baria. With the northern regions of our new possession now quiet, Admiral Bonard turned southward against Vinh-Long, a fortress located on the Mekong. It was taken on 23 March by Lieutenant Colonel Reboul, supported by the fleet.

Despite their small numbers, our forces had to keep possession of a very large tract of country. Many isolated posts were attacked frequently by the rebels, whose audacity was great. On 6 April 1862, insurgents from Tan-Long launched a surprise attack on Saigon, between the arroyo and the fort of Cai Mai. Around 50 huts were burned, a French position compromised, and for a moment we feared for our artillery stores.

The river of Hue, which bore rice to the capital of Annam, was blocked; Emperor Tu Duc, who was fighting a revolt in Tonkin, sued for peace, and a treaty was signed on 5 June 1862 in Saigon. This treaty, concluded between France and Spain on the one hand and Annam on the other, contained the following major provisions:

(i) The subjects of the two nations of France and Spain may practice Christian worship in the kingdom of Annam, and the subjects of this realm, without distinction, who wish to embrace the Christian religion, may also do so freely and without coercion; but those who do not have the desire to become Christians will not be forced to do so.

King Tự Đức (reigned 1847-1883)

(ii) The three complete provinces of Bien-Hoa, Gia-Dinh (Saigon) and Dinh-Tuong (My Tho) and the island of Poulo-Condore are ceded fully and in all sovereignty to France; in addition, French traders may trade freely and move their ships wherever they wish in the great river of Cambodia and in the arms of that river; it will be the same for the French warships sent to carry out surveillance in the same river and its tributaries.

(iii) The king of Annam shall pay as compensation, within a period of 10 years, the sum of four million dollars (the kingdom of Annam having no dollars, the latter was represented by 72 hundredths of a tael).

In addition, the Vinh-Long citadel was to be “rendered to the king of Annam as soon as he had ended the rebellion that exists, by his orders, in the provinces of Gia-Dinh and Dinh-Tuong.”

After this act had been signed, Tu-Duc sought to escape its terms by every manner: the persecution against Christians continued by devious means in Cochinchina; access to ports remained banned, and, by covert means, the subjects of provinces ceded to France were pushed into rebellion against us. By December 1863, an uprising led by the mandarin Quan-Dinh had become very widespread; but with reinforcements requested from Manila and our China Seas naval division, Admiral Bonard managed to suppress it. That done, the treaty of 5 June 1862 was ratified on 14 April 1863 in Hue.

It was at this juncture that Spanish troops left the colony, where they had remained with us for five years, showing great bravery and proving themselves to be worthy heirs of their country’s military glory. The descendants of Rocroi and Saragosse, this time fighting for the same cause, had learned to respect each other.

Nguyễn dynasty mandarin Phan Thanh Giản (1796-1867)

Annam had not yet abandoned hope that we could be persuaded to give up our conquest. For this purpose, an embassy headed by Phan-Than-Gian was sent to Paris. Embarking on 16 July for France, the king’s plenipotentiary envoy requested the return of the three eastern provinces in exchange for financial compensation.

At this time, opinions in France were divided on the question of whether or not to keep our new colony. Public opinion, already excited by the case of Mexico, was increasingly concerned about the dangers of distant expeditions. Opponents of the Cochinchina project had sufficient influence to push for a new treaty to be signed, turning the occupation into a mere protectorate, and leaving us just a few places – Saigon, My Tho, Thu-Dau-Mot and Cholon – connected by military roads.

Fortunately, several competent characters – the Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, Minister of Marine, M Duruy, Minister of Public Education, Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, Senator Baron Brenier, and, in opposition, Thiers and Lambrecht – moved to save our nascent colony. A counter-order was sent and we kept Cochinchina.

Having failed in its attempt to obtain the surrender of the three conquered provinces, the court of Hue did everything possible to make our occupation difficult and costly. It hoped that, tired of the constant sacrifices, we would eventually give up and leave the country. The mandarins of the three western provinces, which remained under the rule of Tu-Duc, continually excited partial revolts on the left bank of the Mekong, and in Cambodia, which became our protectorate by the Treaty of 11 August 1863. Before 1867, our efforts to repress these revolts were ineffective, because the rebels dispersed by our troops immediately took refuge in the lands which were still ruled by Tu-Duc, the real instigator of all these troubles.

Eventually, the intrigues of the Annamite monarch were punished. The sedition he excited in Cambodia and the insurrection he fomented in the north of our possessions were repressed vigorously by Colonel Reboul, Lieutenant Colonel Marchaisse (killed during the uprising), Captain Savin de Larclauze, and Commanders Alleyron, Brière de l’Isle and Domange.

Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière (1807-1876)

Admiral de la Grandière, Governor of Cochinchina, had frequently expressed concern that our colony lacked natural borders, and that the western provinces, which remained Annamite, were serious trouble spots. The most recent events proved that he was right, and as a result, the admiral was allowed to bring these provinces into our possession. An expedition was organised in the greatest secrecy, and from 20-24 June 1867, our troops occupied Vinh-Long, Sa-Dec, Chau-Doc and Ha-Tien, without encountering any resistance.

Phan-Than-Gian, the former envoy of Tu Duc in Paris who was the governor of these provinces, ordered the mandarins to submit, in order to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. Then, refusing the generous offers of Admiral de la Grandière, he poisoned himself, thus becoming a noble victim of the political cunning of the king that he was powerless to avert.

INSURRECTIONS. After the conquest of the three western provinces, the first insurrection which we had to overcome was that of the Plain of Reeds, fomented by an able leader named Tien-Bo. Entrenched in a position he believed to be impregnable, he was flushed out by a column of 400 men, composed largely of native sharpshooters. This failure did not discourage a Cambodian named Por-Kom-Bo, who escaped from Saigon where he had been interned and raised the standard of revolt in Tay-Ninh province.

He believed that all Cambodia would answer his call to protest against the subordinate position accepted by King Norodom; but no one moved, and it only took a little sortie by our Tay-Ninh garrison to put the insurgents to rout. Por-Kom-Bo took refuge in the mountains, where he found new strength among savage tribes and briefly captured the Cambodian ruler, who was only released by troops sent by the governor of Cochinchina.

The Annamite mandarins could not bring themselves to accept the fait accompli. The sons of Phan-Than-Gian, disregarding the wise advice given to them by their father on his death-bed, placed themselves at the head of an insurrectional movement centred on the city of Chau-Doc.

Vietnamese riflemen undergoing training in Saigon

On 30 November 1867, young soldiers of the Marine Infantry commanded by Sergeant Monnier, occupied a small bamboo blockhouse in My-Tho. Suddenly, 1,000 Annamites rushed upon them with loud cries.

The small garrison just had enough time to close the doors, and answered with heavy fire, which put the attackers to flight. However, they returned during the night and set fire to the blockhouse, rendering the position untenable; Sergeant Monnier formed his men into a small squad and rushed at the attackers with fixed bayonets, inflicting many casualties on their enemies.

On the night of 16 June 1868, the rebels attacked the post of Rach-Gia. Entering through a gate which was still under construction, they massacred our sleeping soldiers. The head of the post and a few of his men just had time to seize their arms and they fought like lions, but eventually succumbed to the enemy’s superior numbers. Just one of our soldiers escaped, and thanks to his directions, we were able to launch strong and swift reprisals.

Since that time, there have been only local insurgencies, occurring almost every year at around harvest time, and suppressed easily by our indigenous militias. Overall, Cochinchina has accepted our domination with good grace. Here we have not had to deal with revolts for independence like those of Algeria, which have been made even more formidable by explosions of religious fanaticism. The Buddhist does not, like the Muslim, live in horror of the Christian; neither does he give him offensive nicknames like giaour (dog), a word which the Arabs use so often.

Commander Ernest Doudart de Lagrée (1823-1868)

While we were struggling to consolidate our domination, we did not lose sight of our great economic and scientific interests. An expedition led by Commander Doudart de Lagrée, assisted by Lieutenants Francis Garnier and Delaporte, was charged with exploring the upper Mekong. The mission penetrated as far as Yunnan, where Lagrée died, exhausted by fatigue. Francis Garnier then took command and brought the mission back to Saigon, after a journey of nearly 10,000km, including 6,000km on water. They had the good fortune to observe the total eclipse of 18 August 1868, in a previously inaccessible and unknown region.

The war of 1870 [the Franco-Prussian War] was announced on 6 August to the governor, Admiral de Cornulier-Lucinière. Three days earlier, a German who had arrived on an English steamer warned the Prussian Consul, and several German ships withdrew hastily from Saigon. The admiral immediately fortified the entrance of the Soirap and armed the Juno in order to protect the approaches to Saigon against incursions by enemy ships. He also raised the alarm about a possible attack from the court of Hue and declared martial law in the colony.

The Third Republic was proclaimed in Saigon on 21 October 1870. Following our reverses, the court of Hue, always kept fully informed of our embarrassments, thought this the right moment to make new proposals for the redemption of the ceded provinces. However, they took no action and our colony followed its normal development.

It was Admiral de la Grandière who had the honour of consolidating our conquest in such a powerful way that subsequent insurgencies were, so to speak, no more than insignificant clashes.

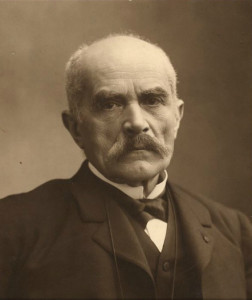

Charles Le Myre de Vilers (1833-1918), photo by ANOM

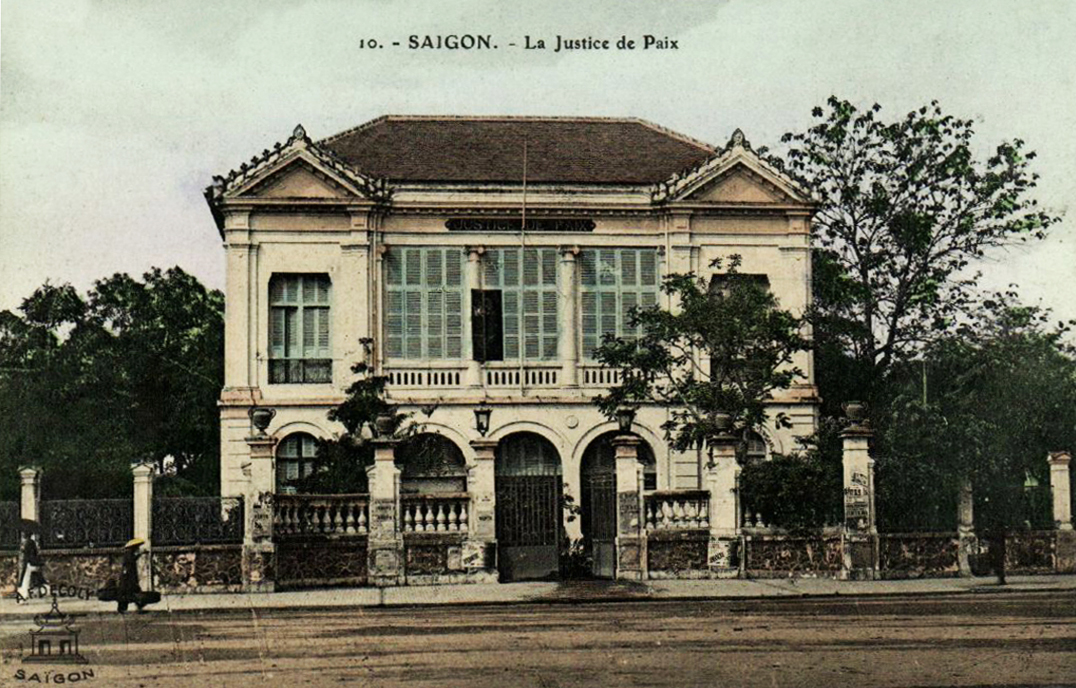

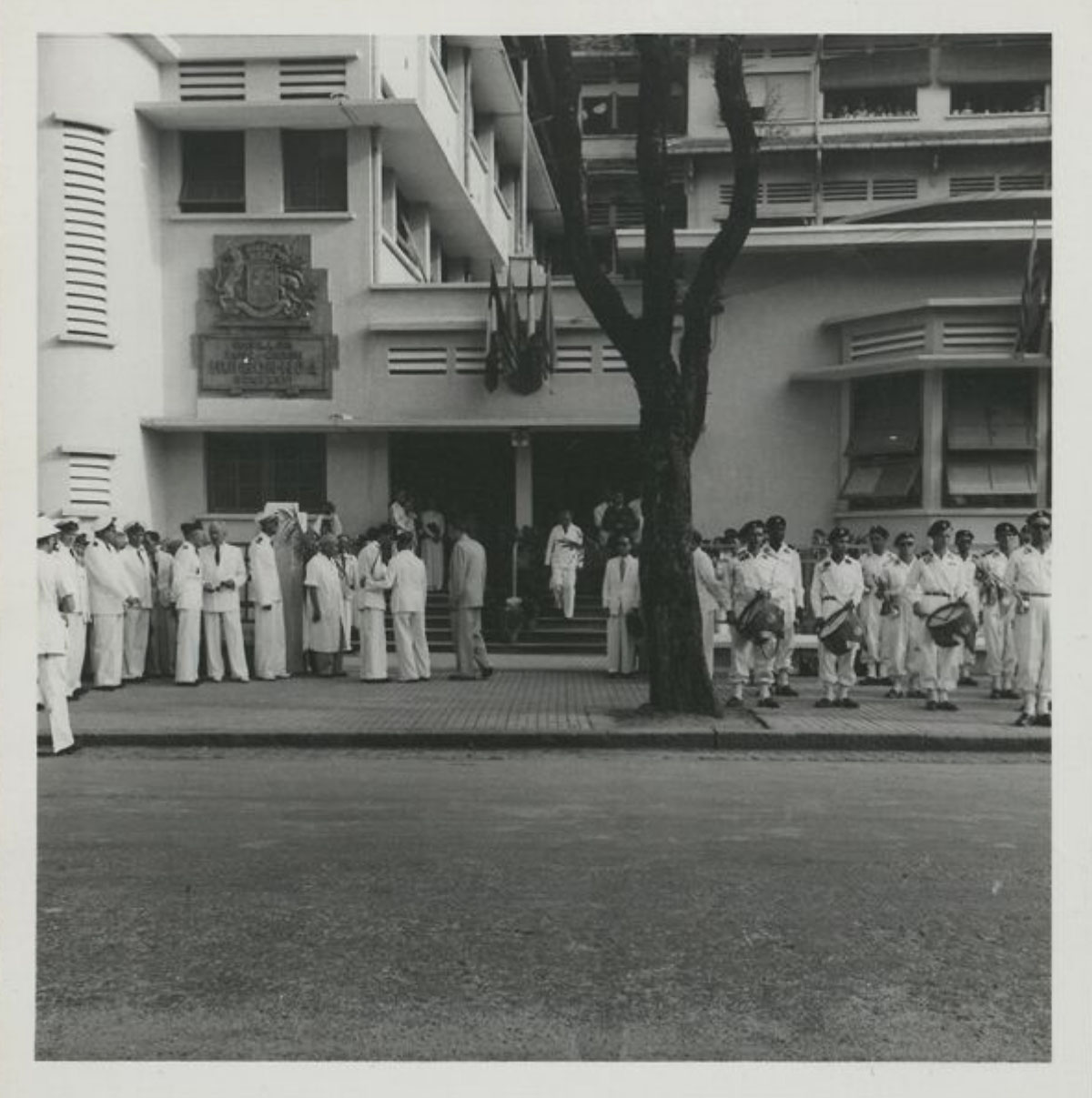

CIVIL REGIME. The arrival of Governor Charles Le Myre de Vilers on 7 July 1879 marked a new era in Cochinchina, the era of civilian rule. It was under Le Myre de Vilers’ government that the first Deputy of Cochinchina, Saigon Mayor Jules Blancsubé, was elected. Charles Thomson succeeded Le Myre de Vilers.

On 17 June 1884, during the governorship of Charles Thomson, the Convention of Phnom Penh was concluded between the French government and King Norodom. This treaty placed the protectorate of Cambodia under more direct and effective French administrative supervision. The protectorate was controlled by a Resident General, under the control of the Governor of Cochinchina. More recently, a decree replaced the Resident General of Cambodia by a Resident Superior.

After a long interim under General Bégin, Charles Thomson was replaced in 1886 by Ange-Michel Filippini. Sadly, M Filippini died in Saigon in November 1887, in the exercise of his functions.

UNION OF INDOCHINA. The decrees of October 1887 established the Indo-Chinese Union, which brought the colony of Cochinchina and the protectorates of Cambodia, Tonkin and Annam together under the authority of a single official: the Governor General of Indo-China.

In November 1887, Ernest Constans, returning from his ambassadorship in China, during which he had negotiated a new treaty of commerce with the court of Peking, accepted the post of Governor General of Indo-China on a temporary basis. After visiting not only Cochinchina and Cambodia, but also Annam and Tonkin, M Constans returned to France. He was replaced as Governor General by Étienne Richaud, who was already Resident General of Annam and Tonkin. In May 1889, M Richaud in turn was replaced as Governor General by Jules Piquet, Governor of French India.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.