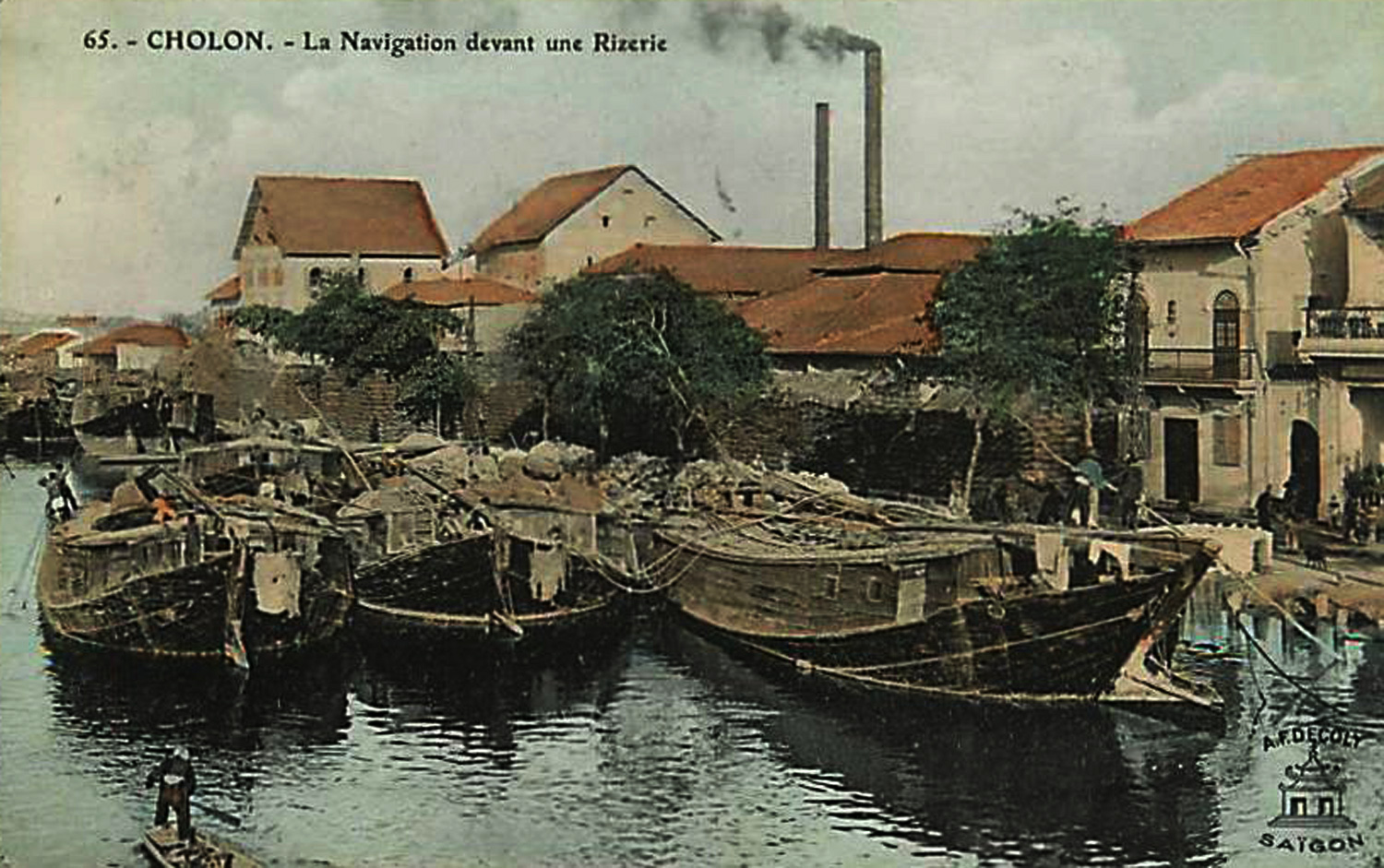

A rice de-husking and blanching factory in Chợ Lớn

A fascinating overview of the economy of Saigon and the south in 1907 from Eugène Jung’s book l’Avenir économique de nos colonies 1: Indo-Chine, Afrique occidentale, Congo, Madagascar (The Economic Future of our Colonies1: Indochina, West Africa, Congo, Madagascar”), Paris, 1908

Cochinchina

Cochinchina has an area of 59,800 square kilometres, much of which is composed of alluvial soil from the Mekong, Donnai and Saigon rivers.

It’s a colony known almost exclusively for its rice culture; but with the opening of new railway lines, there is hope that the higher land to the east will be exploited for a range of other products.

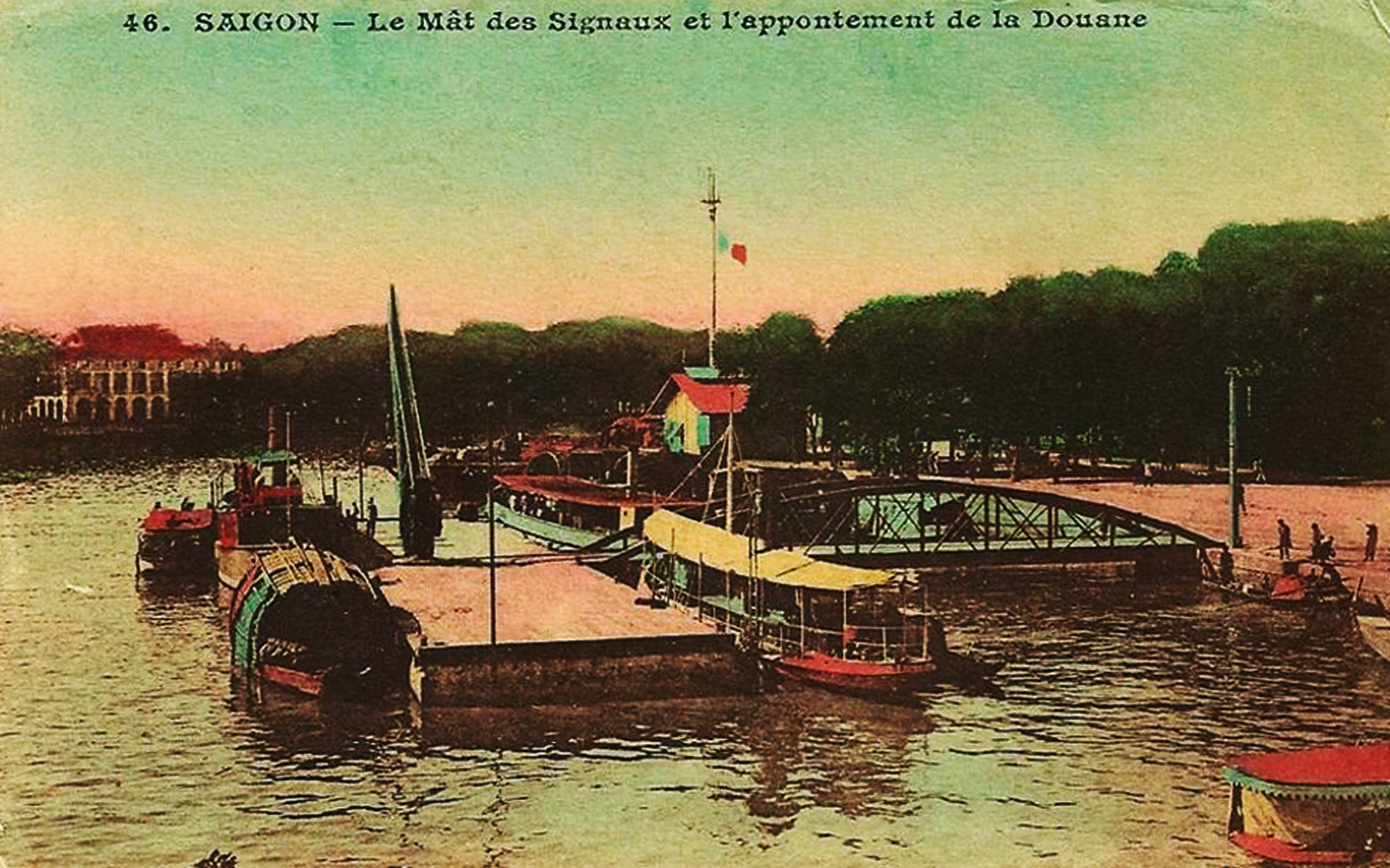

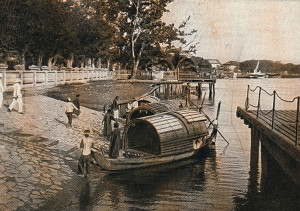

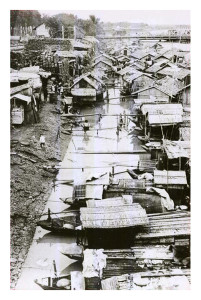

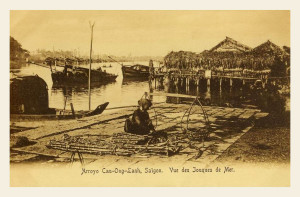

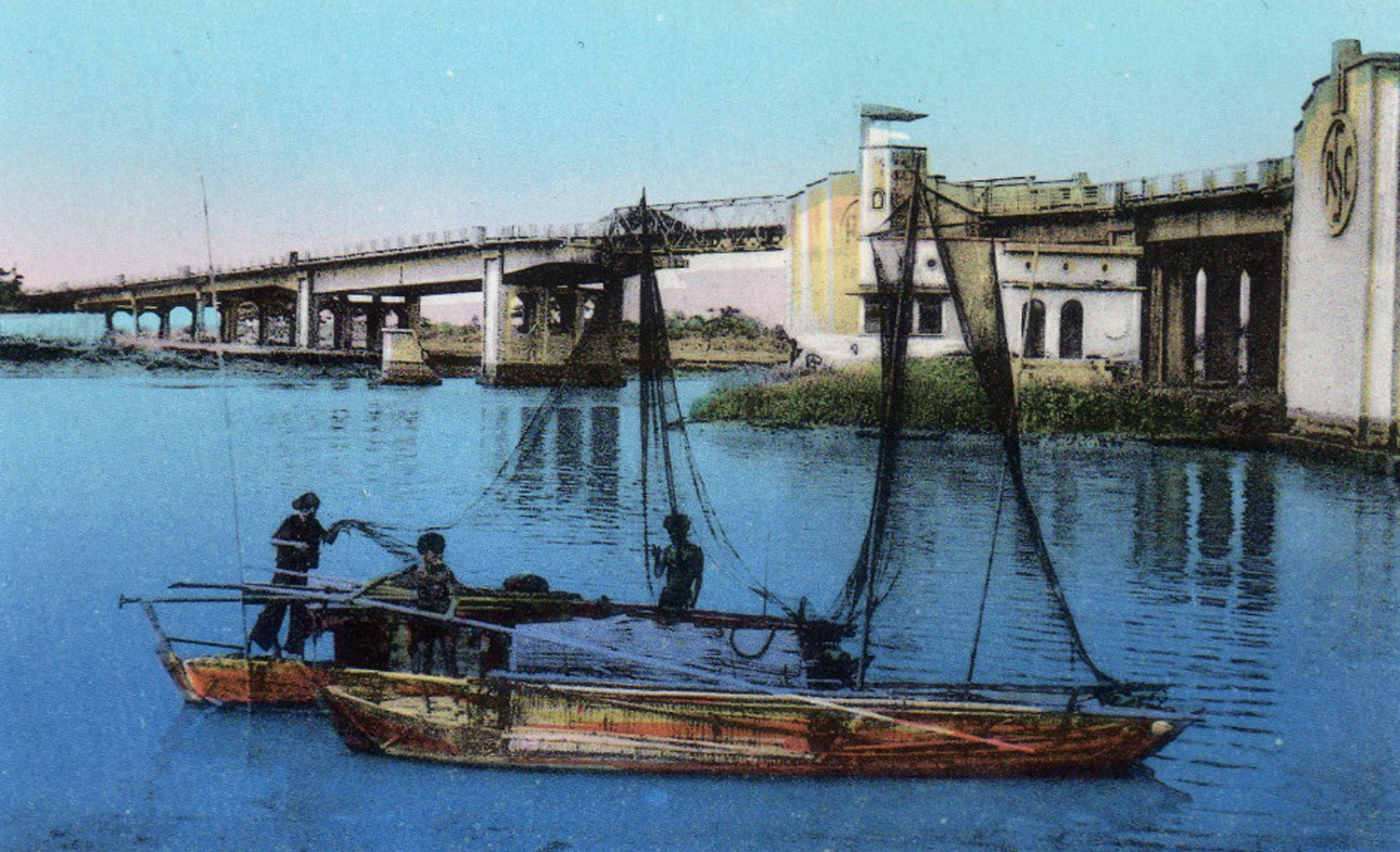

Merchant ships on the arroyo-Chinois

Apart from its major rivers, Cochinchina is crossed by a multitude of other creeks and canals, which permit land irrigation and the movement of boats and junks bringing the crops of the Delta to Saigon. It is extremely rich and it was the first of our colonial possessions not only to cover all of its own expenses but also to make a contribution to the Metropolis. It has been a powerful supporter of the neighbouring territories which form our Indo-Chinese Union.

It’s inhabited by 5,192 French (other than troops) 190 foreigners, 498 mixed-race people and 2,837,787 indigenous people.

It’s almost exclusively a colony of exploitation, home to many important businesses which thrive here and carry out significant transactions.

In 1906, average imports amounted to 143,007,154 francs and exports to 116,612,847 francs. In 1907 it is expected that this figure will be significantly exceeded; but this year is exceptional. Up to 20 September 1907, 1,023,649 tons of rice had already been exported, generating 178 million francs. The tonnage will increase further, perhaps to 1,400,000.

However, only 1,200,000 hectares are currently under cultivation in Cochinchina; if one exploits the remaining two million hectares which remain available and are suitable for rice cultivation, the wealth of Cochinchina will undoubtedly increase in remarkable proportions.

Official infrastructure

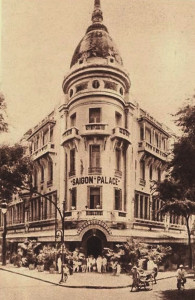

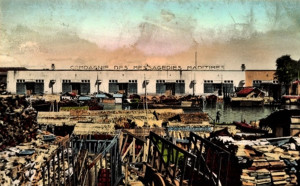

The Messageries fluviales wharf in Saigon

Cochinchina is served by many ships of all nationalities and by several French companies,

The interior is criss-crossed by steamships of the Compagnie des Messageries fluviales de Cochinchine (Cochinchina River Courriers Company). Founded by J Reiff, it was set up as a limited company on 22 May 1881. Its head office is at 43 rue Taitbout in Paris, and its capital is 2 million francs, in shares of 100 francs, costing 320-340 francs. Saigon is its main place of business, with a sub-directorate in Phnom-Penh (Cambodia). Its fleet consists of 12 steel steamships weighing from 300 to 800 tons, 14 river steamships from 40 to 200 tons and eight steel launches. It travels to 123,000 different places in Cochinchina and Cambodia, serving many communities. It receives a 669,562 franc subvention for its domestic services and 48,438 francs for the provision of its Cap-Saint-Jacques service.

Chinese steamships of the Yen-Seng company also provide services on four routes.

Finally, Saigon is the headquarters of the Compagnie française de Cabotage des mers de Chine (French China Sea Navigation Company).

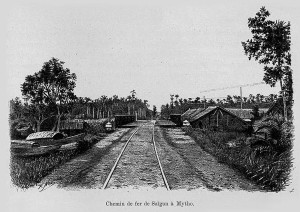

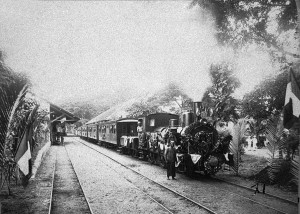

For a long time, Cochinchina has had just two small railway lines, from Saigon to My-Tho on the Mekong (71km) and from Saigon to Cholon (5km). These belong to the Société générale du Chemin de fer de Saïgon à My-Tho and the Société générale des Tramways à vapeur de Cochinchine respectively.

The former is a limited company, founded on 15 November 1881 for a term of 99 years, with capital of 2,378,500 francs in shares of 500 francs reimbursable at 600 francs, and 8,936 bonds of 500 francs at 3%. There are plans for the Saigon to My-Tho line to be extended in future to Tan-An and Can-Tho (95km).

A Saïgon-My Thô line train at Mỹ Tho station – Maison Asie Pacific (MAP)

The Compagnie française de Tramways (Indo-Chine) currently has a network of 29km: Saigon to Cholon via the route basse (low road) tramway; Saigon to Go-Vap; and Saigon to Hoc-Mon, which is capable of extension. A limited company set up with a duration of 50 years, its registered office is at 28, rue Saint-Lazare in Paris. It has capital of 1 million francs, fully-paid shares of 500 francs and 2,300 bonds of 500 francs at 4½%, issued at 475 francs. Transportation of passengers, increasing every year, guarantees the company a very prosperous future.

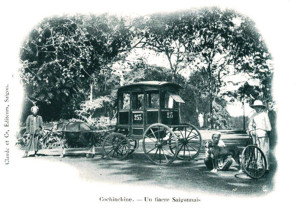

The automobile firm Ippolito et Cie, founded in 1900, offers regular services between Saigon and Tay-Ninh (106km) on the Cambodian border, as well as to Bien-Hoa, Ba-Ria and Cap Saint-Jacques.

Finally, the new railway line from Saigon to Khanh-Hoa (Annam), belonging to the Indo-Chinese [government] rail network, is currently operational as far as Tan-Linh, 120kms from Saigon.

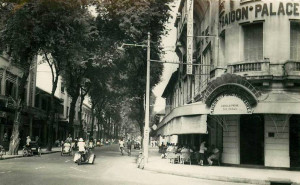

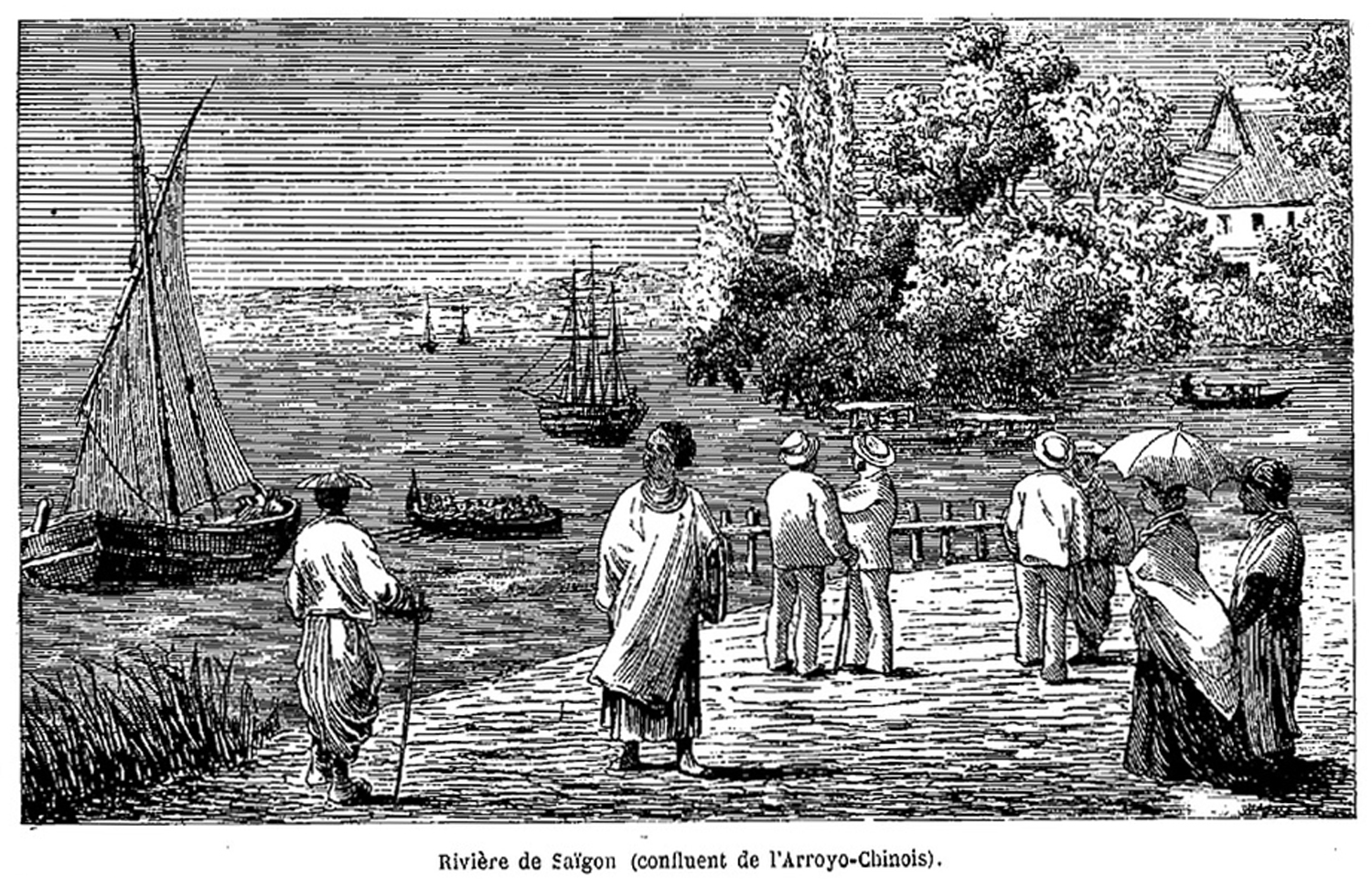

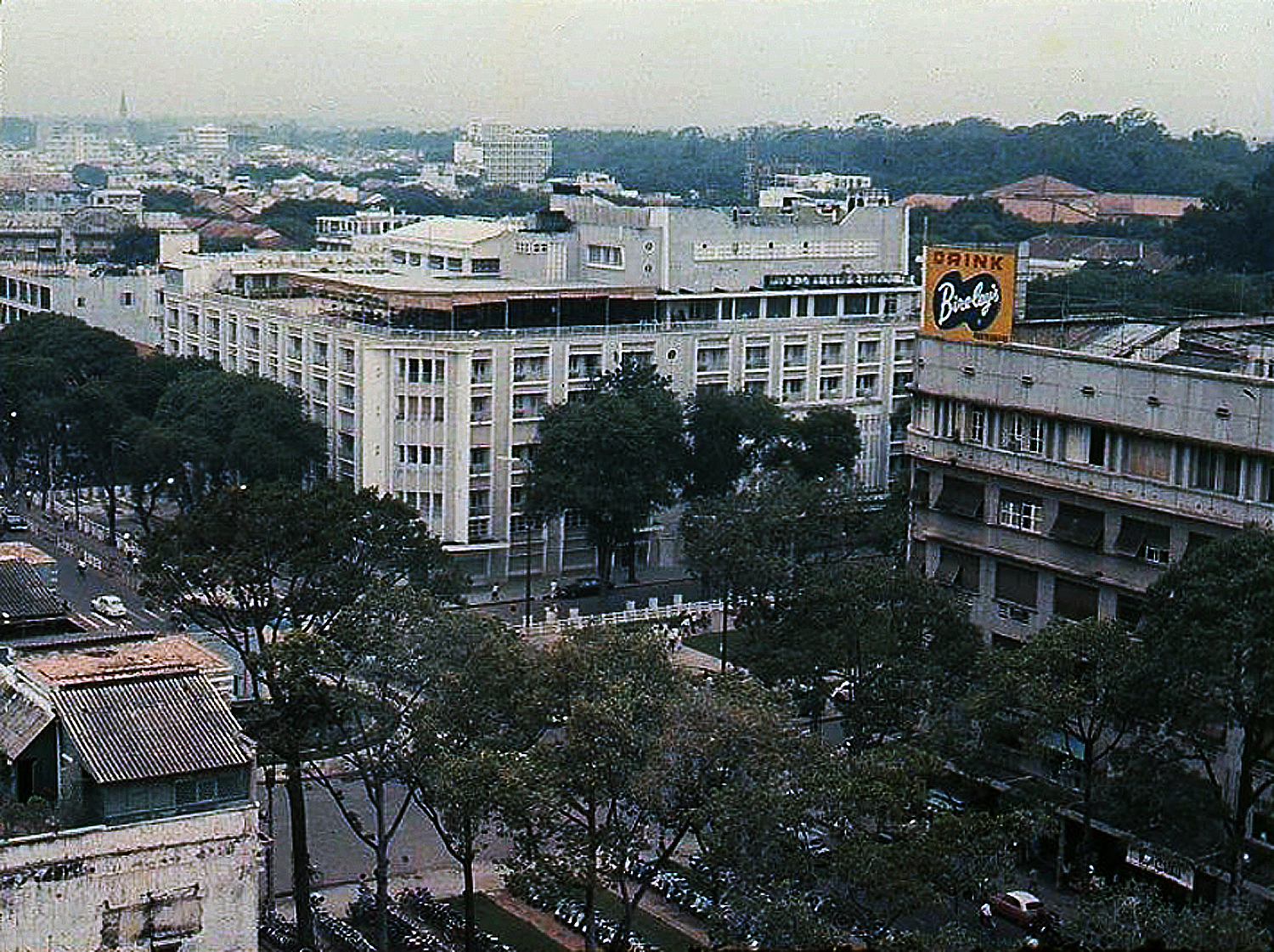

All these transportation routes leave from Saigon, which is a major city (54,000 inhabitants, including 14,000 Chinese) and a port of the first order. This port has an area of 24,000m². A new port costing several million francs is currently under construction, with depots and 1,100m of quays, but the nature of the subsoil has caused some unfortunate construction problems. In fact, we were warned about this by several old Cochinchina hands, but we did not think it necessary to pay them any attention. When completed, it will have cost 10,394,100 francs. In 1907, the general government spent 220,000 piastres on this project.

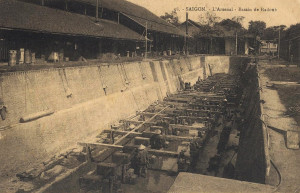

Saigon has the peculiarity of being situated 70km from the sea (at Cap Saint-Jacques) and still being accessible by its river to ships of the largest tonnage. It has a naval port with an arsenal and a 160m dry dock, where both warships and other vessels may be repaired.

Saigon – the new quays and docks

In 1906, 526 steamships (including 216 French and 169 English) entered the port carrying 130,752,846 francs of merchandise, while 456 (including 171 French) left carrying 116,039,273 francs of merchandise.

Other ports, including Hong-Chong (Gulf of Siam), Ca-Mau, Rach-Gia and Ha-Tien, can receive only boats of low draught, such as junks.

Exports from Saigon consists of rice, salted fish, cotton, pepper, cardamom, gambodge (tree resin), indigo, animal horns and copra; imports include flour, wines, liqueurs, fabrics, oils, soaps and machines.

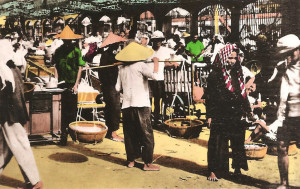

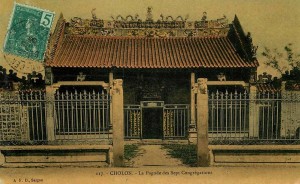

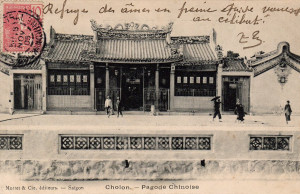

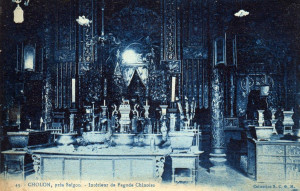

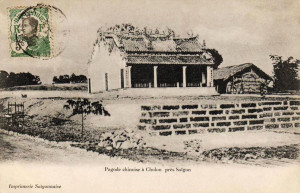

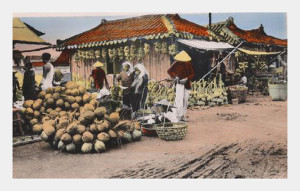

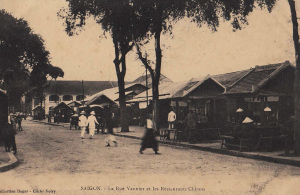

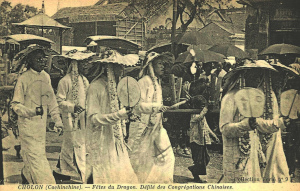

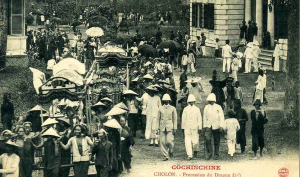

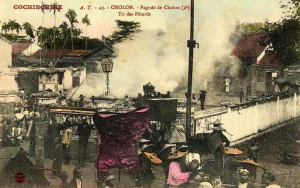

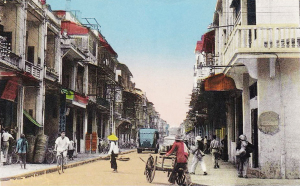

Among the inland cities that make up the economic infrastructure of the colony, it is worth mentioning the great Chinese city of Cholon, located 5km from Saigon, with 138,000 inhabitants, of which 41,891 are Chinese. It has quays of 4,520m in length and every year in its factories, 4 or 5 million piculs of rice are placed in sacks for delivery to Saigon or export abroad. Thousands of junks and boats ply its canals. It is also an industrial city of the first order.

My-Tho, situated on one of the arms of the Mekong, is a hub for many steamship services which go to Cambodia, roam the arroyos of Cochinchina or travel along the coast.

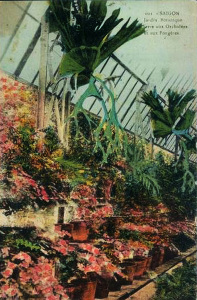

Saigon has a practical school for Asian mechanics, a vocational school where students learn how to manufacture machinery and furniture, a Directorate of Land Mapping and Topography, a Directorate of Agriculture, a Botanical and Zoological Garden, an Institute of Scientific Research, a Pasteur Institute, an Indochinese Studies Society which publishes studies on agricultural trials and has its own museum, a Forestry Service, a Syndicate of Planters, a Chamber of Commerce and a Chamber of Agriculture.

Domestic products

Rice paddies in Cochinchina

Rice is the main product of Cochinchina, which gives rise to two crops each year. One should cite in particular the rice of Vinh-Long province, greatly sought after in Europe for distillation. The other main domestic products are pepper, cotton, ramie (Boehmeria nivea), corn, indigo, sugar cane, mulberry, silk, coffee, areca nut, betel, tobacco, coconut, copra, peanuts, jute, wood of all species, cardamom, wax, honey, joss sticks, fish and salt.

As we said at the beginning, Cochinchina includes high lands on the borders of Annam and Cambodia, which explains the diversity of production in this country, although other sectors are currently paid less attention than rice and pepper production.

Pepper is grown especially in the province of Ha-Tien, on the island of Phu-Quoc (which also contains the most valuable timber) and to a lesse extent in the provinces of Ba-Ria. Bien-Hoa and Chau-Doc. The Chinese devote themselves with ardour to the cultivation of this commodity and Indo-China is now its fourth largest exporter.

Tobacco is a major crop in some areas, including Hoc-Mon, where day by day the indigenous people open up more land to cultivation.

Our tax on tobacco came as a surprise to the Annamites, who were suddenly required to obtain a permit for carrying any more than 20 kilos of tobacco. The limit has since been reduced further, first to 10 kilos and then to just 1 kilo. In order to obtain a permit, they are forced to travel 17km to the Customs and Excise office in Cholon, and only after this can they return home to pick up their small loads. In some areas, these vexations have resulted in the complete abandonment of tobacco production and an exodus of residents. It would perhaps have been preferable to develop the lands that produced the tobacco first.

A pepper plantation in Phú Quốc

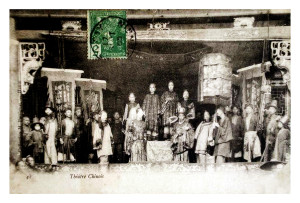

Some Annamite and Chinese industries are quite sizeable. Largest of all are the seven major Chinese rice de-husking and blanching factories in Cholon. These are expensive facilities, built with the latest steam-powered machinery, and they operate with perfect efficiency.

In Cholon one may still find the famous Cai-Mai pottery. This is now produced by the Société Tung-Hoa et Cie, which manufactures glazed terracotta vases, garden ornaments and ceramic building materials.

Manufacturers of glass and leather, dyeing works, sculpture workshops, silk and cotton weavers, pewter manufacturers, timber mills, brick kilns and junk construction and repair yards may also be found here.

Outside Cholon, one must mention the tortoiseshell crafts of Ha-Tien; the granite of Gia-Dinh and Bien-Hoa; the silks of Chau-Doc; the woven cottons and silks of Long-Xuyen; the sampots of Chau-Doc; the metalwork of Bien-Hoa; and the pottery and kaolin deposits of Thu-Dau-Mot.

European companies

European agricultural concessions are quite numerous in Cochinchina. In total there are about a hundred; but on average they are quite small.

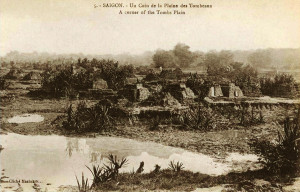

While the larger and more important ones amongst them are thriving, others await the contribution of outside capital, because the work they do in developing new rice fields can be particularly costly, for example in the famous Plain of Reeds.

Among the most prosperous ones, we must mention the rice paddies of Monsieur Paris, lawyer, member of the Colonial Council and President of the Chamber of Agriculture. After many years of toil and expense, his company arrived at a happy outcome.

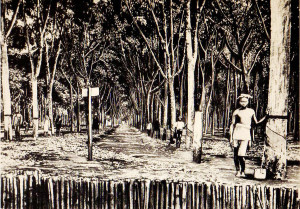

A rubber plantation northeast of Saigon

Of particular note is the Plantation Suzannah, located at km 67 on the Saigon to Khanh-Hoa railway line. It is situated 175km above sea level and includes 2,600 acres of exceptionally rich volcanic soil which ranges from 25m to 40m deep. A joint stock company with a capital of 150,000 piastres, it was established in 1907 by the founders of a research company sponsored by Monsieur Louis Caseau. It took the company two years of testing before they could begin to cultivate rubber. Today, this is its main crop, with 30,000 plants grown in 1907 and 100,000 in 1908. To cover its expenses, the Plantation Suzannah also grows mulberry trees, cassava, castor, tobacco and peanuts. All of its agricultural tools are mechanical.

In the province of Ba-Ria, Messrs Arcillon and Bertrand grow coffee and pepper. In the province of Gia-Dinh, several European companies grow rice, fruit trees, coffee and rubber and breed livestock. In Hong-Chong, the successors of the late Monsieur Paul Blanchy, former president of the Colonial Council, are known for their excellent pepper plants. And in Than-Hoa, next to the Mekong, the Société Michel Vilaz et Cie owns a large number of rice fields.

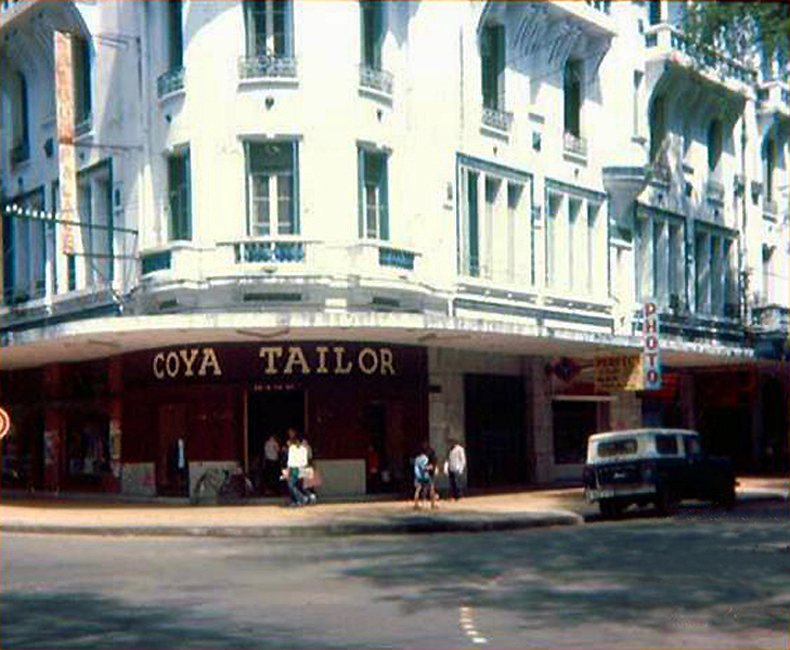

Merchant houses may be found in large numbers in Saigon, engaged in both import and export activity.

The proximity of Cambodia and Laos permits the import of products of all kinds, including fabrics, trinkets, hardware and a range of local specialities, which are brought for storage in Saigon and, along with rice and pepper, become the focus of much commercial activity.

We must not forget that many transactions are in the hands of the Chinese, whose merchant houses have considerable capital and largely monopolise the trade with neighbouring countries.

Chợ Lớn – the departure of a junk

Saigon imports goods from Hong-Kong (8,920,739 francs), Singapore (10,463,076 francs), Japan, Siam and China (23,671,410 francs), the Philippines, Java, the British East Indies, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies.

It also exports goods to the same localities: Hong-Kong (21,256,898 francs), Japan (7,492,878), Singapore (6,087,206 francs), the Philippines (19,757,394 francs), Siam and Java (3,941,776 francs), China (13,186,000 francs), etc, etc.

International trade in the other ports of Rach-Gia (imports of 409,771 francs, exports of 319.387, mainly with Singapore, Bangkok and China), Ha-Tien, Ca-Mau and Hong-Chong is under the control of Chinese merchants.

Overall, however, Europeans play a fairly important part, controlling imports from France and other French colonies (59,545,074 francs), England (709,500 francs) and America (1,464,205 francs); and exports to France and other French colonies (28,710,614 francs), England (400,000 francs), Germany (180,000 francs) and the Netherlands (350,000 francs).

European merchant houses in Saigon include the Maison Denis-Frères of Bordeaux; Dumarest et fils of Marseille; Paris, Mangon et Denandre of Paris; the Société Française d’Exportation of Paris; the Maison Speidel et Cie of Paris; and Weil Wormser et successeurs, representing the mill owners of Rouen. In general, these houses are involved in the import and export of all major products, as well as consignment and chartering.

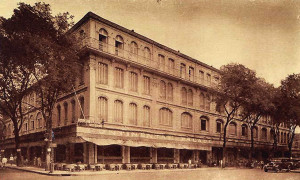

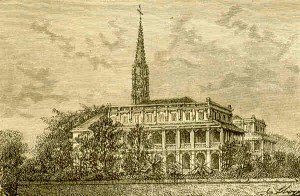

The Messageries maritimes headquarters

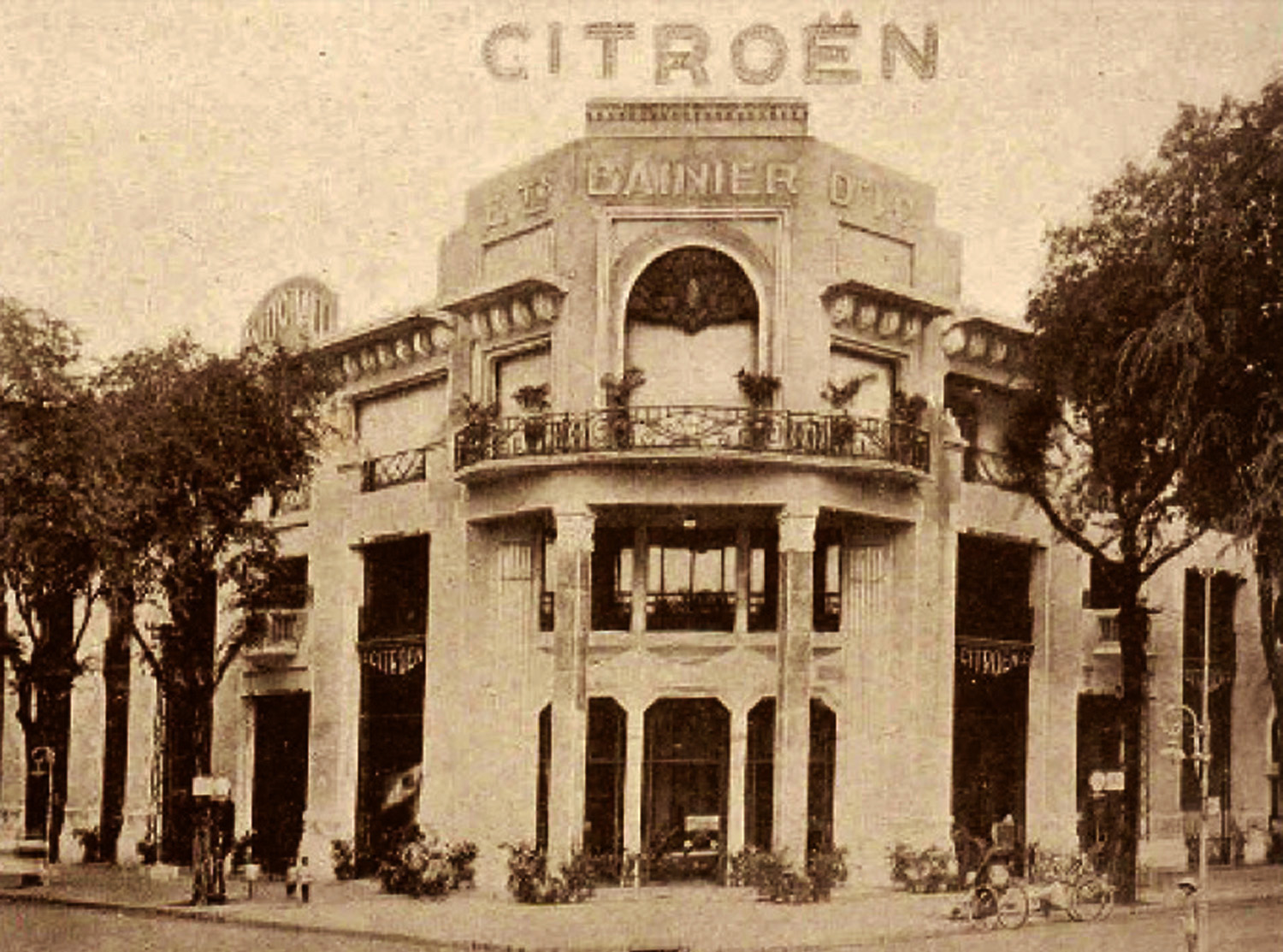

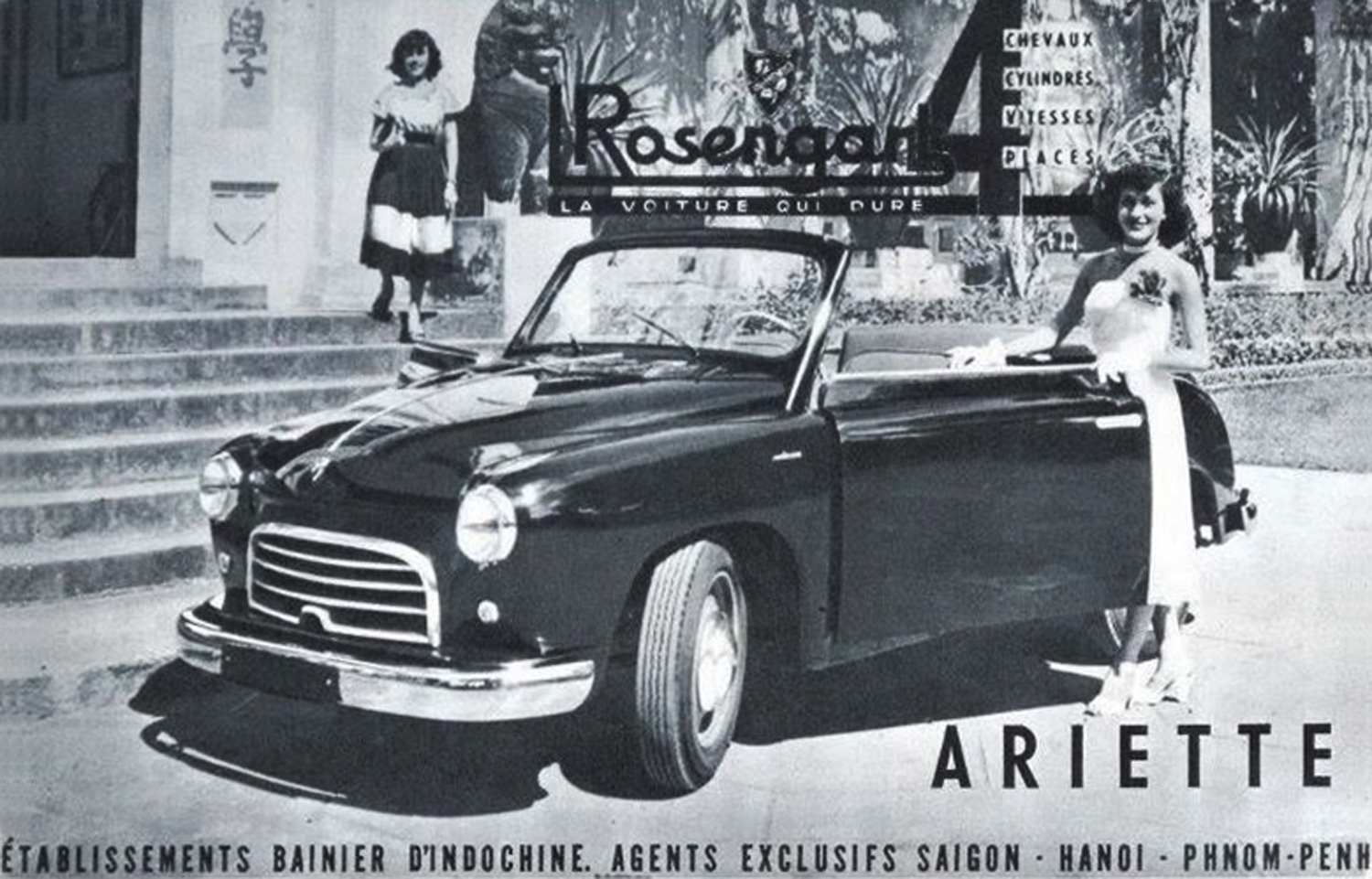

Apart from these companies, we may also find all kinds of interesting European enterprises: innkeepers, gunsmiths, insurance companies, automobile dealers and jewelers, as well as shipowners like the Maison Allatini et Cie.

Among the best-known houses are Omnium Français (head office in Dijon), the Société Bordelaise Indo-Chinoise (head office in Bordeaux) and the Compagnie Coloniale d’Exportation.

The banks of Cochinchina include the Banque de l’Indo-Chine, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China (of which Messrs Speidel et Cie are the agents), the Hong-Kong and Shanghaï Bank, and the new Banque de la Cochinchine.

Industry is brilliantly represented in Cochinchina.

Firstly, the workshops of the Compagnie des Messageries Fluviales employ more than 300 artisans who build ships both for the company and for the local administration. These workshops are equipped to carry out larger repairs and also to assist the Naval Arsenal as required.

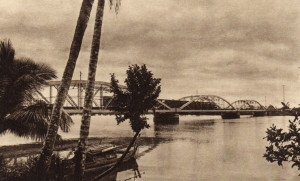

A large number of entrepreneurs is involved in major works projects. The Société de construction de Levallois-Perret (headquartered in Paris) builds bridges, port facilities and reservoirs; the Maison Graf, Jacque et Cie (rue Martel, Paris) has construction workshops in Khanh-Hoï, near Saïgon; and the Société française Industrielle d’Extrême-Orient (headquartered at 11 avenue de l’Opéra, Paris) builds railway equipment and major works in iron. Not to mention MM. Hermenier, entrepreneurs, Braisot Ducellier, etc.

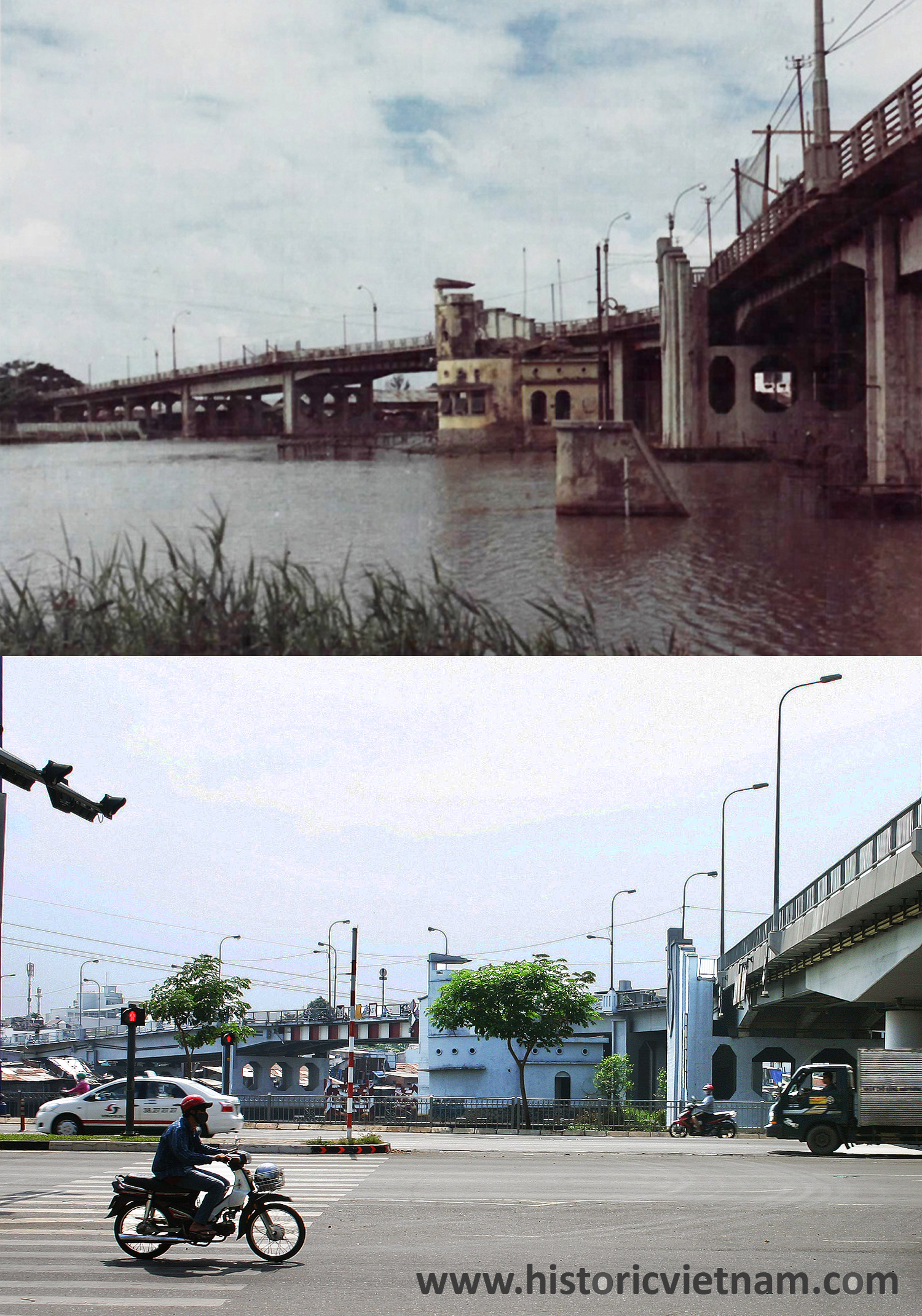

The Bình Lợi bridge, built in 1902 by the Société de construction de Levallois-Perret

Amongst the other important French industries are the ice factory of Monsieur Larue, whose plant includes two machines with respective capacity of 1,000 and 500 kilos; the distillery of the Société française des Distilleries de l’Indo-Chine, based in Cholon; the distillery of Messrs Mazet, also in Cholon; the Société pour l’exploitation des Alcools indigènes en Cochinchine et au Cambodge, with capital of 100,000 piastres, headquartered in Saigon; the Rizeries de l’Union, in Cholon; and the Rizeries de l’Orient, also in Cholon, with French, German and Chinese shareholders.

We must not forget the printing and lithographic works of Monsieur Claude, whose skilled workers publish books in French and in Chinese characters; and the coachbuilders of Monsieur J. Trigant.

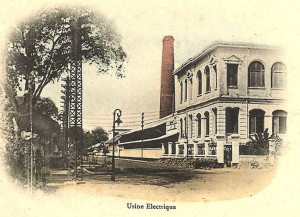

The Société d’Electricité de Saïgon is a limited company with capital of 700,000 francs, with shares of 500 francs, distributing an interest of 5%. The company, whose registered office is at 20 rue Mogador in Paris, operates an electric power station in Saigon and supplies and distributes electricity throughout the city.

The Société anonyme des Eaux et Electricité de l’Indo-Chine, with its registered office at 58 rue de Londres in Paris, was founded on 2 April 1900 with the aim of purchasing and exploiting all factories, concessions and contracts for water and electricity services already installed or to be installed in Saigon, Cholon and Phnom Penh. Under its concession agreement, the company secured guaranteed receipts of 162,000 francs for Saigon, 280,000 francs for Cholon and 363,000 francs for Phnom Penh. The Company’s capital is 2,500,000 francs, in fully paid shares of 500 francs and 6,000 bonds of 500 francs at 4½% paid, issued at 467.50 francs by the Banque Industrielle et Coloniale.

Saigon’s first electric power station, opened in 1896

Finally, we should mention the canning of pineapple, mangosteen and other fruits of the country by Monsieur J Abos in Saigon; the wooden furniture and sculpture workshops of Monsieur Bonnet in Saigon; the soap company of Monsieur Hugand in Saigon; the brick factory of Monsieur Mulot in Vinh-Long; the cotton factory of Messrs Émile Nam Hee and Ly Dang in Cholon; and the quarries of Messrs Loesch-Frères in the province of Bien-Hoa, which are equipped with every modern facility.

The economic future

The potential future of agriculture in Cochinchina is bright. In the famous Plain of Reeds, for example, huge tracts of land are now barren and waiting for development capital. With constant irrigation, we can guarantee two superb crops each year, bringing significant returns. Do not forget, however, that these results are not immediate: for the first two years, we must prepare by removing the salt deposited on land, building dykes, digging irrigation canals, all considerable work in a country with a depressing climate. It is therefore necessary to have access to large amounts of capital.

In the province of Ha-Tien and on the island of Phu-Quoc, pepper can be planted over large areas; but we must remember that duty exemption or reduced duty in France is limited to a certain quantity, and that the remainder is subject to heavy taxation in line with world market prices.

The An Lộc Plantation

On higher ground there is potential to create rich plantations, like that of Suzannah. However, success is contingent on several years of research and hard work and many would-be planters have failed.

The exploitation of forests and their products will also be increasingly possible with the opening of the new railway lines.

Several years ago, the Director of Agriculture of Cochinchina told us: “In our colony, according to the regions, one can grow grain products, Java peanuts (from which combustible oil can be manufactured), cotton, sugar cane, jute, indigo, cocoa, mulberry, coconut, copra, Liberian coffee and pepper. However, in order to succeed here, you must set up a limited or other company, so that a director returning on leave to France does not leave the future of the enterprise in the hands of a single employee. And of course, a company is always more influential in its dealings with the government.”

The observation of the Director of Department of Agriculture was and is still accurate; but what that officer could not say is that it is essential to rethink the working conditions demanded by the growers’ unions and to tackle the issues of working conditions and the competence of the courts in matters of labour.

A move in this direction was made in 1906 by a group of the settlers who had suffered as a result of the strongly incompetent laws, decrees, circulars on the matter issued by the Ministry of Colonies, all of which were influenced by the lobbying of organisations such as Défense des Indigènes (Defence of Local People) who are made up largely of those who have never set foot in a colony and have no interest in doing so.

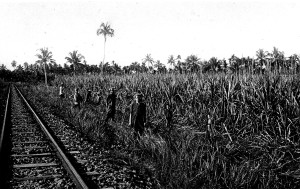

Sugar canes next to the tramway line in Thủ Dầu Một

What we say is all the more true since Monsieur Outrey, Inspector of Civil Service of Western Cochinchina, sent a letter to the Lieutenant Governor on the establishment of a Colonisation Office to safeguard the interests of European settlers in relation to those of the natives.

It requests that the administration supports the Europeans in their disputes with indigenous employees who attempt to evade their obligations. It also recommends, in addition, the gradual substitution of the indigenous workforce with new agricultural machinery.

Among the industries which we still have to create in Cochinchina, one must cite a distillery for perfumed essences from either cultivated or natural plants; a factory for producing rush mats; a factory for producing sacks in which to ship seeds and grain; and a cotton manufacturing plant (although since it is essential to ensure a good supply of the raw material, it is best for such a plant to be set up on plantations owned by the company that wants to start the factory).

On the subject of trade, let us finish with some comments by Monsieur Schneegans, President of the Chamber of Commerce of Saigon, addressed to Dupleix Committee:

“Cochinchina has many French and foreign import-export houses. He who would like to set up a new company must have significant capital to compete with the old established merchant houses, and even then, he is likely to encounter at the beginning almost insurmountable difficulties.”

“The retail trade is almost entirely in the hands of a few Chinese and French traders who cater more than sufficiently for the needs of the current European population.”

A Saigon dockland scene

To this we must add that the foreign merchant houses of Saigon are generally large commissionnaires which buy from and sell to wealthy Chinese merchants. Their business is thriving – more than one of them exports between 200,000 and 300,000 tons of rice annually.

Finally, in Saigon, the foreign merchant houses have no need of the administration; they act outside of it, which is not the case in other parts of Indo-China. They also work with Annamite auxiliaries who have direct interests in the business, while elsewhere in Indo-China the local people seek only administrative posts.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.