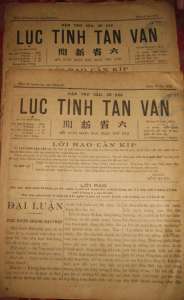

George Dürrwell spent nearly three decades working for the Cochinchina legal service. His 1911 memoirs, Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910 (My Dear Cochinchina, 30 years of impressions and memories, February 1881-1910) afford us a fascinating picture of life in early 20th century Saigon and Chợ Lớn. This is part 2 of a three-part excerpt from the book.

To read part 1 of this serialisation, click here.

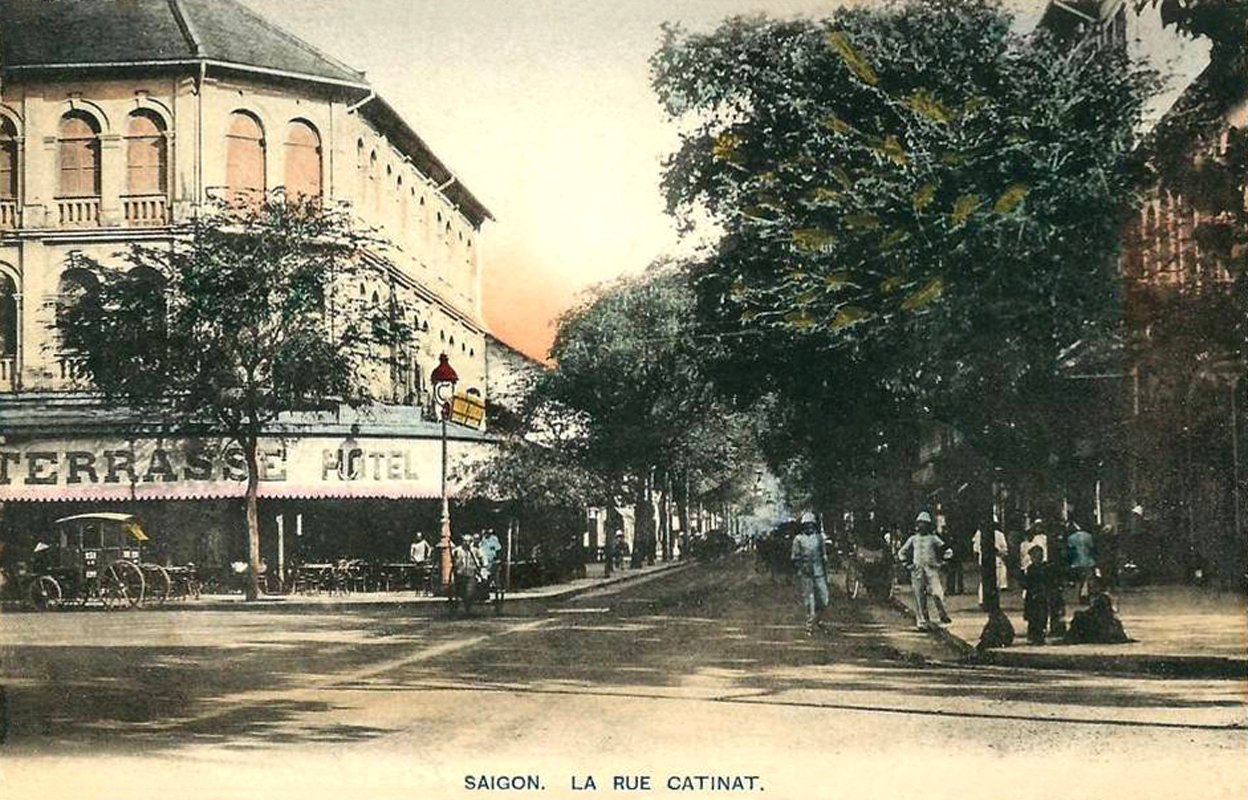

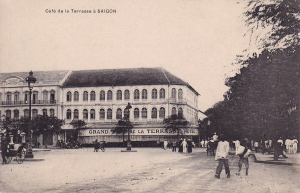

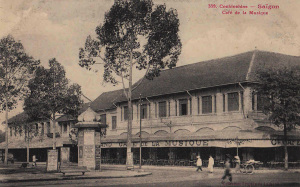

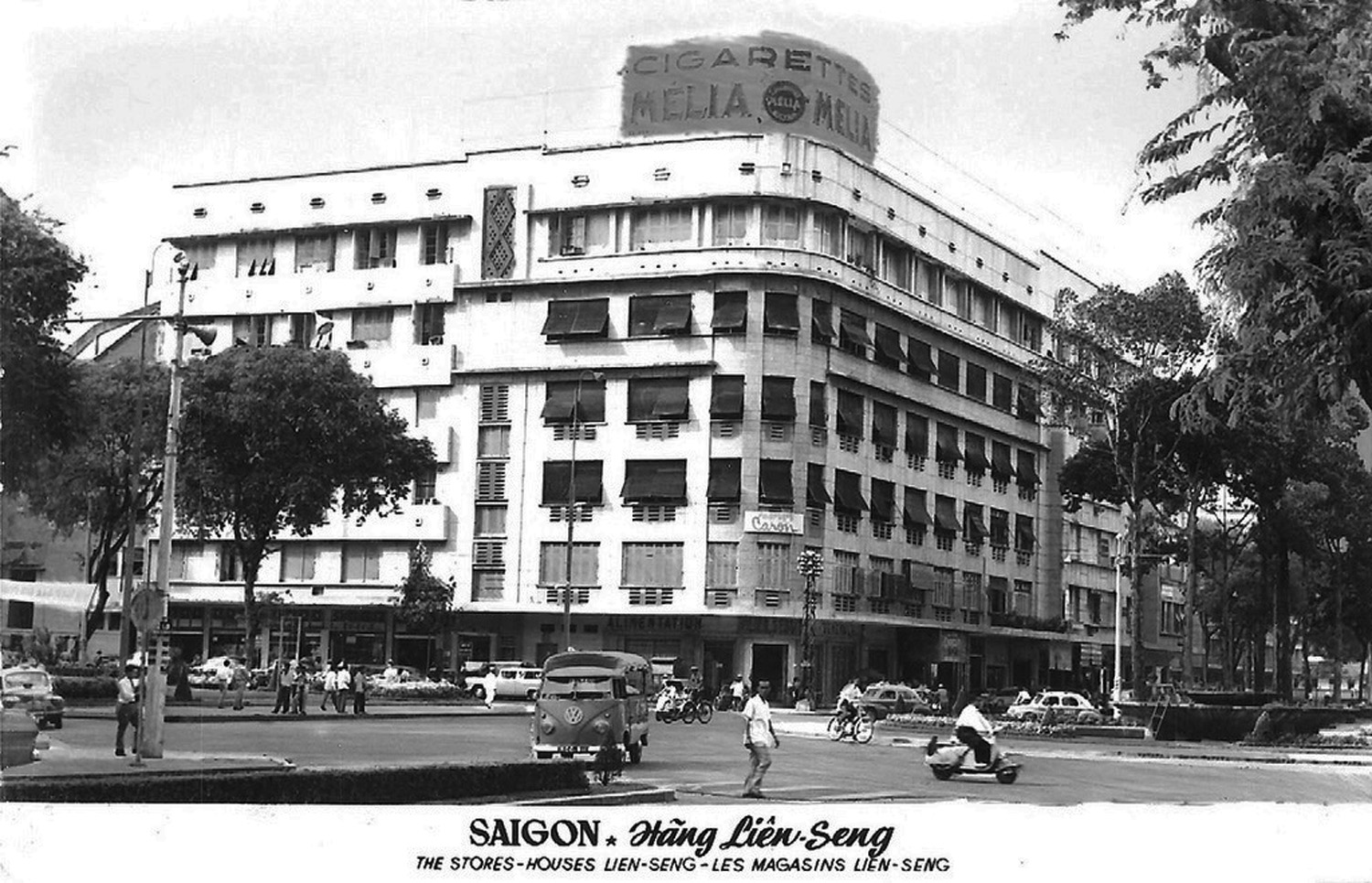

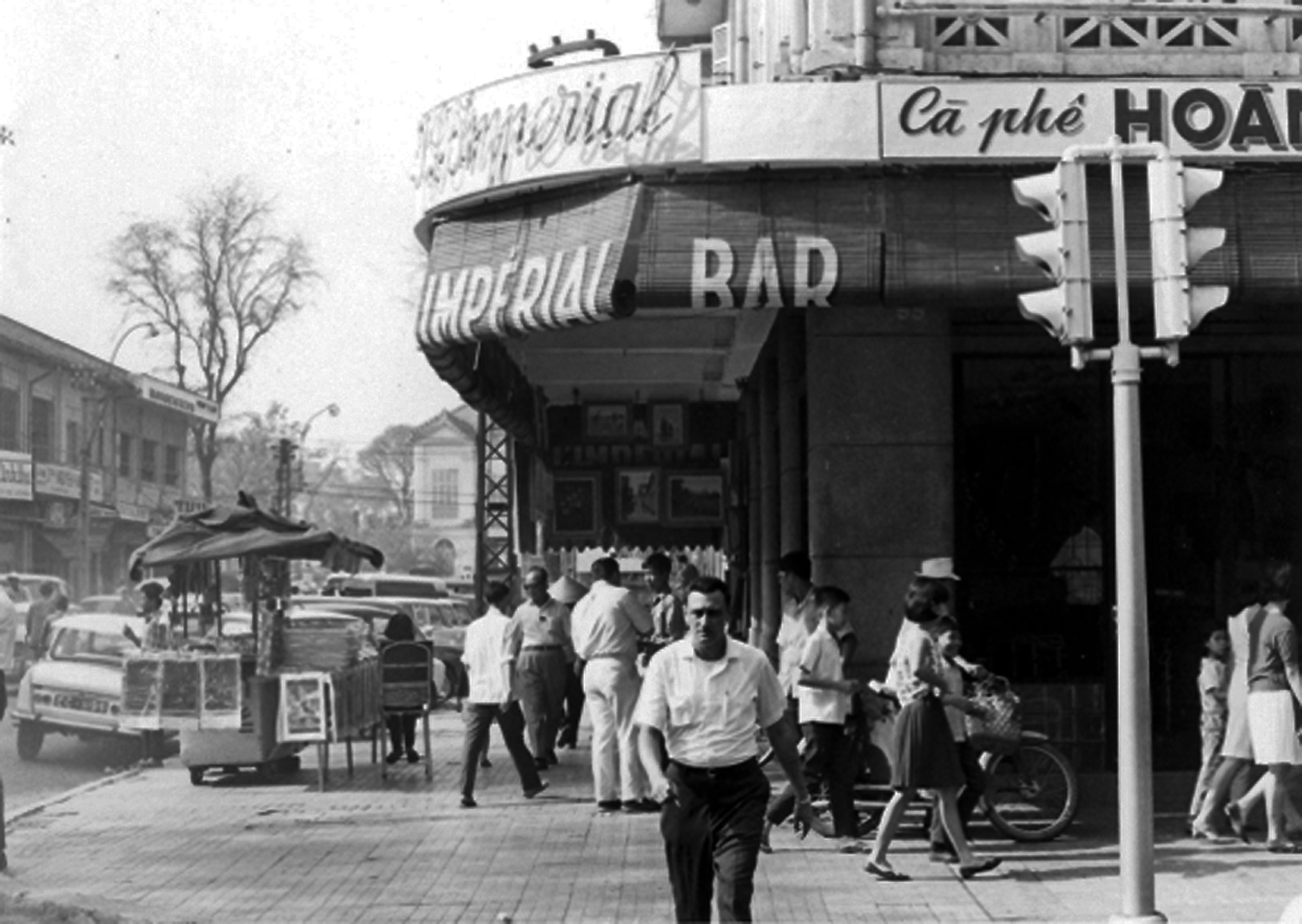

The terrace of the Grand Hôtel De La Rotonde

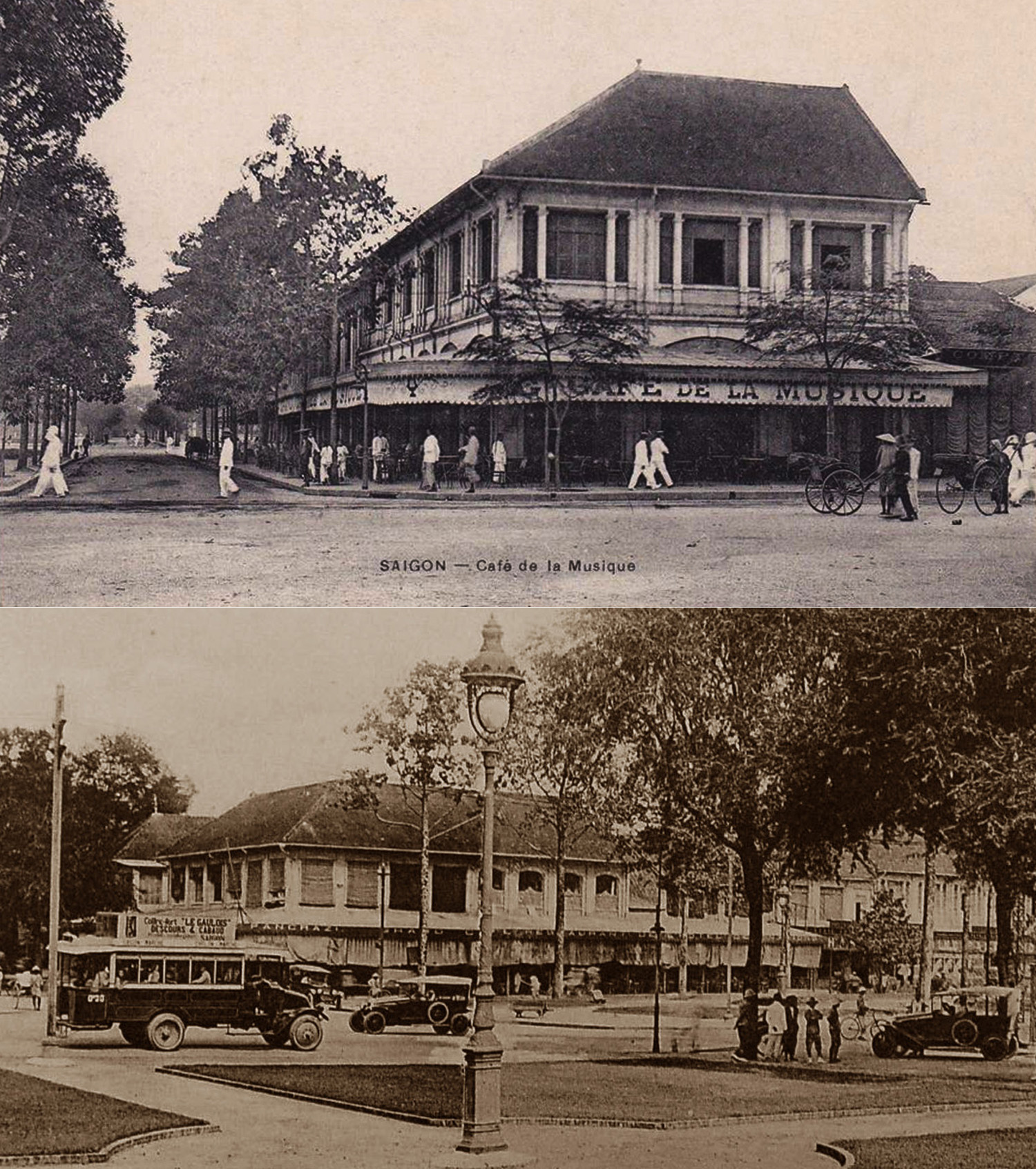

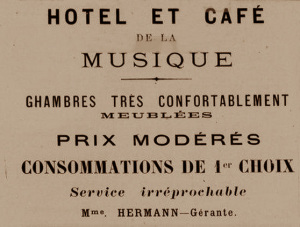

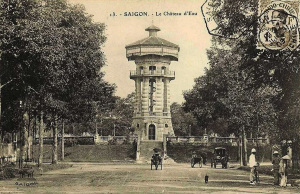

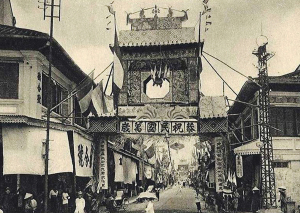

It’s 6pm. The cafés fill with customers and groups begin to form around small tables. Gossipers’ tongues wag while the concert orchestras throw their discordant notes to the wind. The squares and the streets become increasingly animated and noisy, with pedestrians and carriages, automobiles and pousses-pousses crossing this way and that: all of Saigon is outdoors!

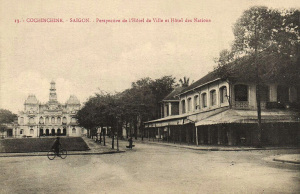

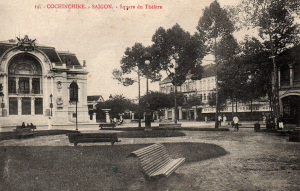

The focus of this exuberant scene is the Municipal Theatre, which presents a very stately air with its vast monumental staircase and high-arched open portico framing artistically sculpted allegorical figures. Flooded at this time of the evening by the last rays of a bright sun, its white façade is tinted a pale purple of infinite sweetness. Then suddenly, the curtain of night falls, almost without transition. Saigon is lit up, but the lighting is very poor, despite the pretty penny spent from the municipal budget on the profusion of electric lamps. This is truly “light hidden under a bushel.” Only the place du Théâtre forms a bright spot amidst the darkness.

The Saigon Municipal Theatre, inaugurated in 1900

From October to April, when the theatre season is in full swing, the entertainment of the evening extends long into the night. The Theatre and the adjacent hotels and cafés overflow onto the streets, transporting the intense nightlife of the French boulevard some four thousand leagues from the great city of Paris to this remote little corner of Asia, where the French soul has already become so deeply rooted.

By midnight, “the day is over,” as the song says. The Theatre closes its doors and turns off its lights, and with them are extinguished the lights of the square and surrounding streets. On the terrace of the Grand Hôtel Continental, there remain just a few groups of late diners, several incorrigible gamblers playing bridge or poker, and here and there a few clowns who have stayed up to contemplate the moon. Good luck to them all – and to all a good night.

The arrival of the theatre company is the big social event of the year in Saigon. Well in advance, it becomes the major subject of conversation and it is also advertised in the windows of our chic bookshops, along with portraits of the performers who are so impatiently expected: the ladies, of course, take the place of honour. Some of the city’s so-called arbiters of elegance are snobbish enough to travel to Singapore in order to be the first to contemplate the stars that will come to us from France: Ave maris stella!

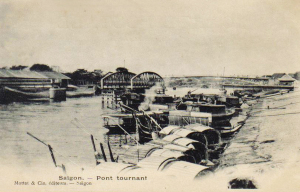

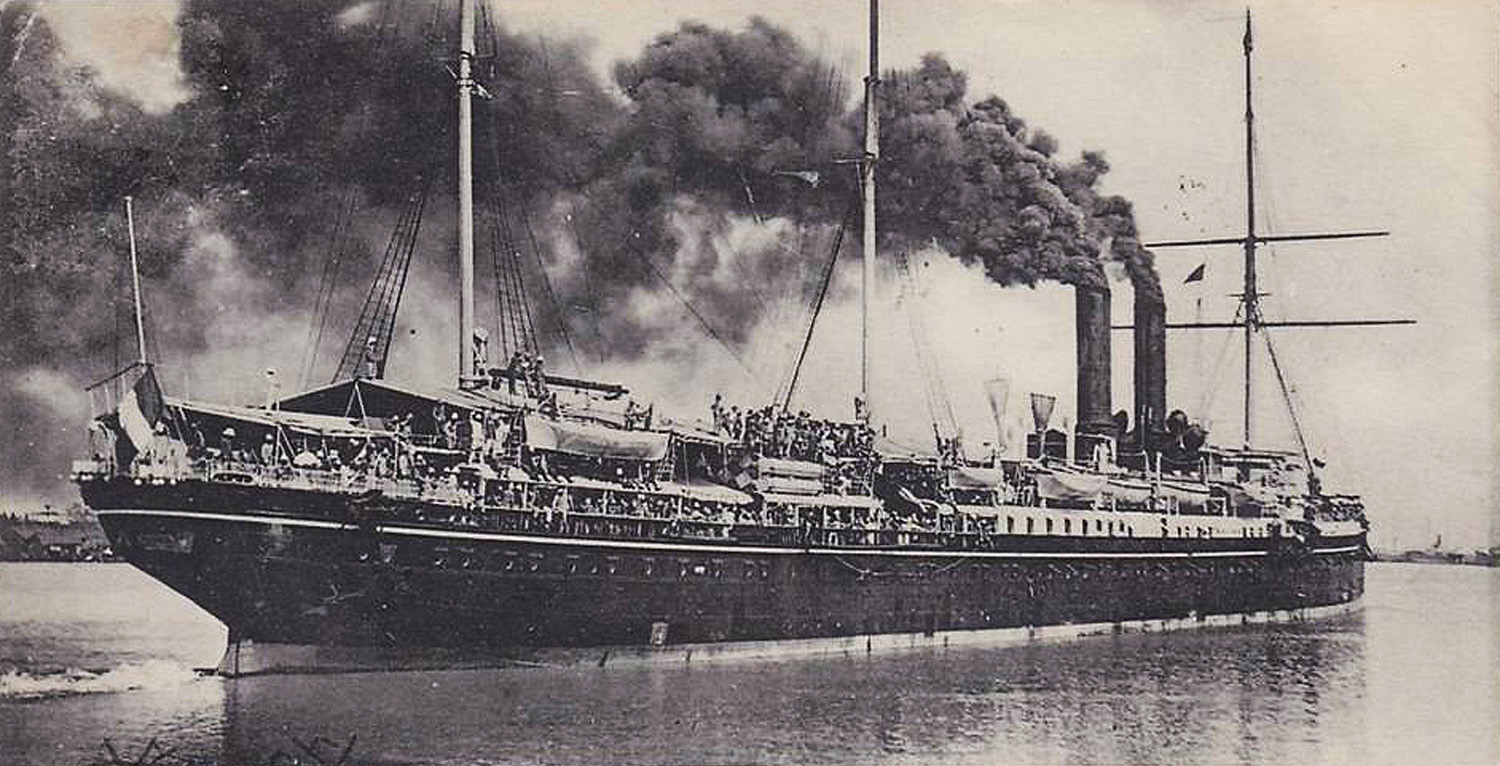

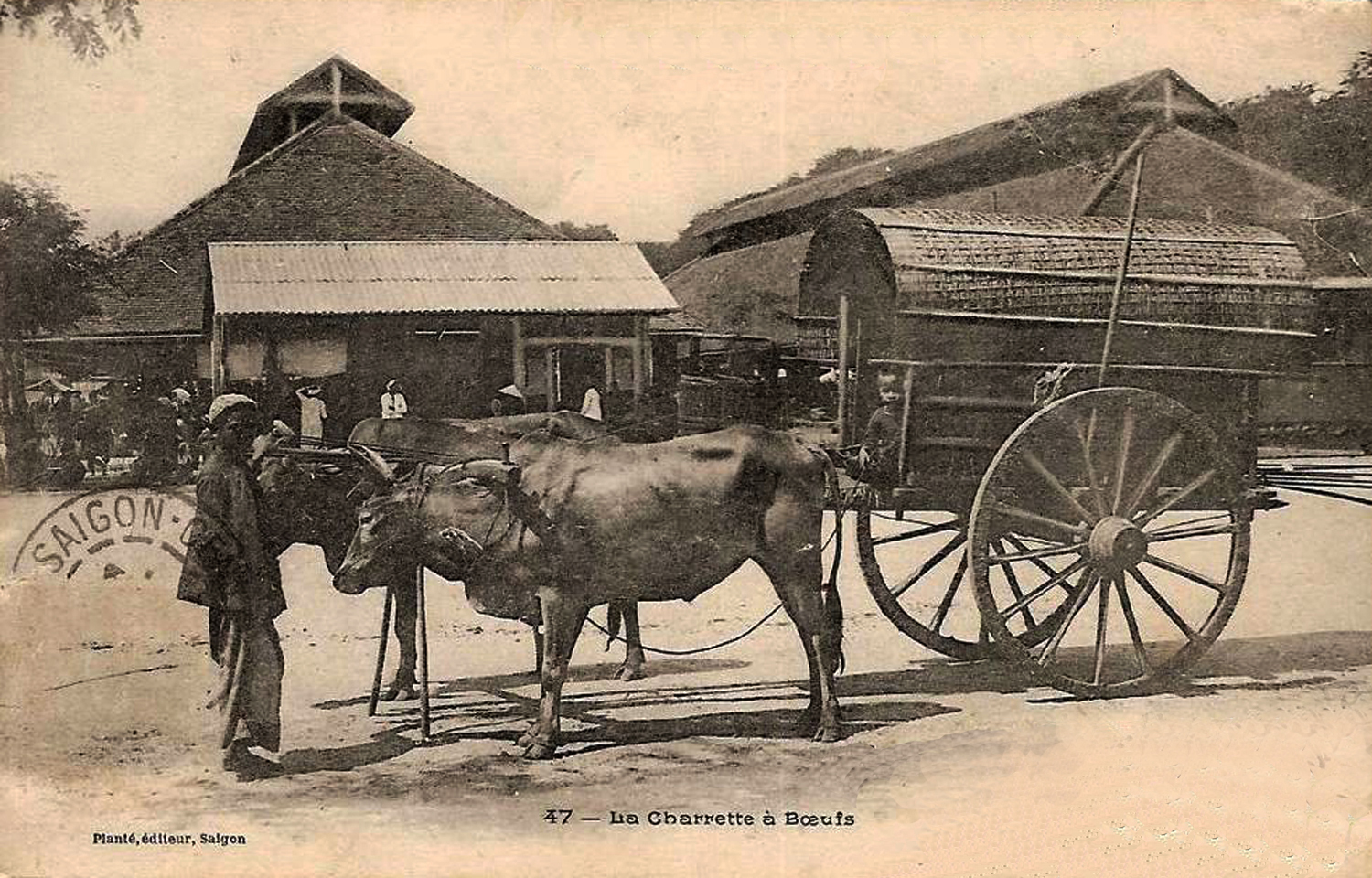

Greeting arrivals at the Messageries maritimes pier in the late 1800s

Finally, the big day arrives. The boat is signalled from the Cap; it enters the river and heads towards Nha-Be. Immediately, all of Saigon’s high society gets dressed up and invades the pier of the Messageries maritimes. After negotiating the last loop of the river, the great courier ship advances majestically into port and wastes no time docking. As soon as the gangway is in place, it is immediately stormed by the crowd, which eagerly spreads itself onto the deck. The impact of all those waxed moustaches and starched collars and cuffs is naturally lost in the crowd and many of our hungry socialites are inevitably obliged to return home empty-handed, with only the platonic satisfaction of having witnessed the arrival of their idols. However, most of them are content, and for good reason, in this special sport where many are called but few are chosen. Then calm returns, as theatre lovers bravely begin to study their scores and all Saigon awaits the minor intrigues which inevitably attend the presence of thespians. Some days later, the Theatre solemnly opens its doors to serve the gathering crowd of attentive spectators. Once more, we are treated to that venerable masterpiece of Gounod, the inevitable Faust, which every year is featured mercilessly in our opening programme. Saigon’s theatre season has begun, and that’s it for the next six months.

The score of Gounod’s Faust

The Saigon public have a reputation for being connoisseurs, and they are therefore very difficult to satisfy. In fact, among the self-appointed art critics, there are some who have never attended any theatrical performances other than those of Landerneau or Pont-à-Mousson. But no matter; it is fashionable to be a connoisseur and each tries to be one, judging with equal severity the débuts of the unfortunate artists and the efforts of their director. Many circumstances, however, argue in their favour. For example, the almost insurmountable difficulties of recruitment for performances in the Far East and the consequent lack of homogeneity of the troupe; not to mention the rigours of a climate which constantly threatens the artists’ health and often attacks their vocal cords; and finally, the excessive labour imposed on them to rehearse a programme which changes every day.

There is, in fact, a remedy for this state of affairs, and I would like to suggest it to the honourable committee which is entrusted with the organisation of our annual theatre programme. In my humble opinion, it would be wise to cease the performance of cumbersome operas with full orchestral accompaniment which require special staging and a standard of performances that only our Music Academy is able to achieve. Instead, the offerings should be limited to some light comedies and comic operettas whose spirit and quality is so exclusively French. I know that my proposal will make our excellent amateur critics leap with indignation, and I can’t offer any cure for that: however, on their return to France, they can at least console themselves by attending performances in Landerneau or Pont-à-Mousson.

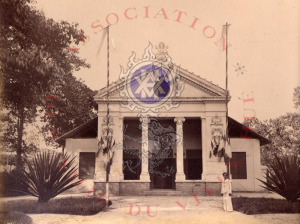

The former Saigon Municipal Theatre (Association des Amis du Vieux Huế)

Our new Theatre, opened on 15 January 1900 on the occasion of the visit by Prince Waldemar of Denmark, is undoubtedly a very beautiful monument, worthy in every respect of our beautiful Saigon. It has, moreover, even excited the jealousy of the incomparable Hanoi; and that says it all.

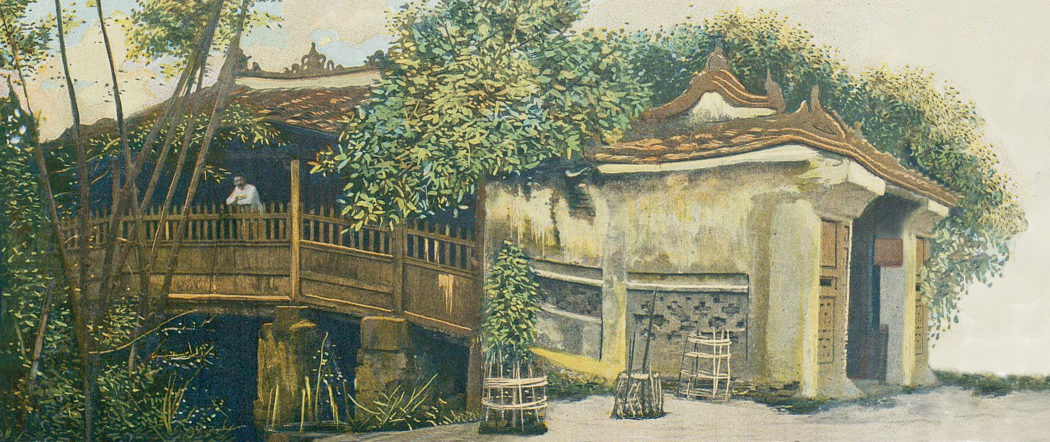

But I would be ungrateful if I didn’t also mention our former theatre, so small and so simply decorated, yet so cosy and intimate, surrounded by lawns and shaded by large trees. There, we saw no “dressing to impress,” no show of luxury; we attended without any fuss, as if we were attending a family gathering, and we always came out happy. All the old Saigonnais, myself and my contemporaries, certainly regretted the loss of this lovely theatre in its corner of greenery. But we must, it seems, march with progress, using a catchphrase like that of the seller of the first boxes of sardines in Nantes: “Always for the better.”

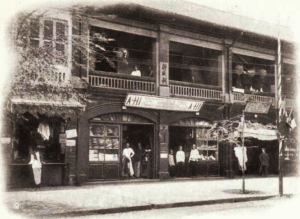

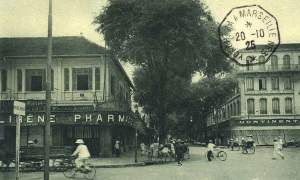

Like a Parisian boulevard, the rue Catinat has had its characters who have lived a little of its life, and whose absence is noted and regretted.

Rue de Bangkok, Saigon

A good example is the former official who became the landlord of several large buildings and could invariably be found perched at the corner of rue de Lagrandière. His thick crop of white hair, cut in the style of Titus, served as a contrast to his amiable ruddy face, a sign of good living. Always smiling, he would sit and watch the passers by, and for him, each was a friend to whom he extended his hand.

Then, in the vicinity of the Grand Hôtel Continental, at all hours of the day and night, we could once find a character with an opulent black beard and a booming voice with a touch of a Gironde accent which resounded across the square. He knew everything about Saigon the day after he arrived, and all Saigon knew and loved him.

And there too once went a perky little man, trotting daintily along boulevard Charner [Nguyễn Huệ] with a triumphant waxed moustache. That was our “king of automobiles.”

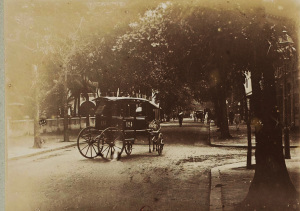

A carriage crew waiting outside the Marine Arsenal

Also operating in this area of the city was one of the friendliest people in our legal office. Dressed elegantly in his light jacket, he would stride along the street with his nose in the air, like the ogre in Tom Thumb, sniffing the fresh and fragrant scent of…. female flesh. Yes, he was out hunting, and you would always find his prey just a few steps in front of him.

Today, the judiciary is still represented in the rue Catinat by a friendly group which we call familiarly “the Fifth Chamber,” whose members wander along the pavement with slow, rhythmic steps, chatting about the interests of their clients. Happily when I pass them today I don’t have to count the missing, as they are still numerous in this country where the dead go quickly.

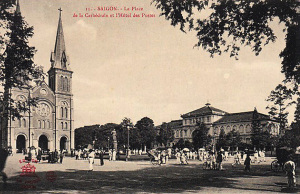

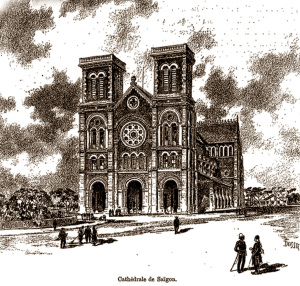

From the rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn] to the place de la Cathédrale, the rue Catinat climbs between two rows of government buildings, on which it would be pointless to dwell. The same must be said for the Cathedral, which similarly deserves little attention. Completed in 1880, it replaced the modest little wooden chapel that once stood on the present site of one wing of the Christian Brothers’ Institution Taberd. It is therefore one of the oldest monuments in modern Saigon, but it is certainly not one of the best – its inelegant mass is enhanced only by its two front towers.

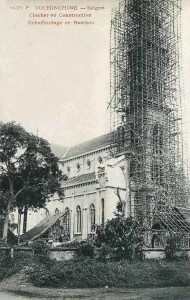

The bell tower of the Huyện Sỹ Church under construction in 1905

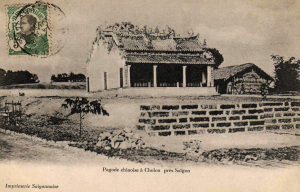

I much prefer the pretty little church [Huyện Sỹ Church] which was built next to the high road to Cholon, according to plans drawn up by an artist in a cassock, and with the posthumous piastres of an old Annamite Crésus in search of absolution.

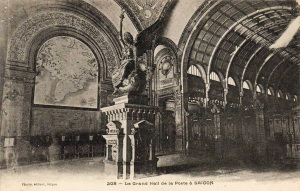

In the same way, I prefer the elegant Hôtel des Postes, which was built a few years ago in the immediate vicinity of the Cathedral. I followed with great interest the various phases of its installation, and have even contributed, in a very small way, to its interior decor. But I see you are smiling in disbelief, so let me explain….

The Indochina Postal Administration was placed under the direction of a great man, an outstanding public servant who remains etched on the memory of all who knew him. Hard on himself, he was also hard on others, but his spirit of high equity and impeccable righteousness, the extent of his technical knowledge and his tireless work ethic made him the model department head, a man for whom no detail could be left unattended. And it is to him that the colony owes the organisation of its admirable telegraph network.

Today only old Cochinchinois can still remember the tenacity and energy with which he carried out this gigantic work. His epic battles with the elephants of Annam, who took pleasure in shaking and demolishing the telegraph poles, are also legendary in Saigon. He left us knowing that if all had not loved him, he had at least forced everyone to hold him in high esteem. And is not this the highest praise that a public servant can hope for?

Saigon Cathedral and Post Office

I had, in fact, quite frankly sympathised with him in the early days of my arrival in Cochinchina, and out of this shared sympathy was born a strong friendship marked by frequent meetings. I also never forget our Sunday walks along the paths of suburban Saigon: with such a guide, a veritable walking encyclopaedia, each of these walks was for me a lesson of the most captivating interest.

One can expect that the construction and development of a new building to house his Postal Service would not leave our man indifferent, and indeed, it provided him with a unique opportunity to apply his infinite skills and energy. As soon as dawn broke, he was everywhere, keeping an eye on everything, sometimes emerging from the basement of the Post Office like a cricket coming out of his hole, sometimes appearing like a genie of the Bastille on the roof ridge of the building.

One morning, I found him perched high on scaffolding which had been erected in the vast central hall, brush in hand, exerting his topographic talents on one of the large maps which decorated the walls. “Climb up here to help me,” he shouted from his perch. I happily climbed up the bamboo ladder, and, installing myself next to him. immediately set to work, marking with strong artistic design the exact location of the good town of Chau-Doc, “capital of mosquitoes.”

The interior of Saigon Post Office

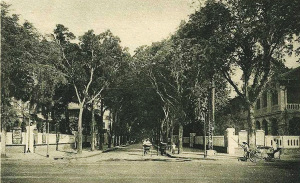

Behind the Cathedral, a wide boulevard stretches the entire length of the plateau from the Botanical Gardens up to rue MacMahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa]. Baptised with the gracious name of His Majesty King Norodom of Cambodia, this beautiful avenue, lined with tamarind trees, provides access to the Palace of the Government General. This imposing monument, the elegant proportions of which harmonise perfectly with the greenery around it, stands in the middle of a large park full of old trees which extend their high foliage into the adjacent Jardin de la Ville (City Park).

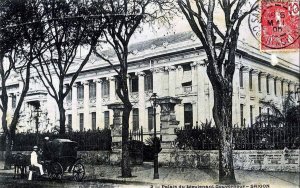

For over 30 years, the Palace of the Government General has been home to the high functionaries to whom the government of the Third Republic successively entrusted the fate of the colony – first the Governors of our Cochinchina, and then, after the consommation of the beneficent Union of Indochina, to the Governors General of Indochina, on those occasions when they visited their southern capital. When I landed in Saigon, the palace was looked after by an energetic and shrewd administrator, one of those men of whom one can say, with reason, “he’s a real character,” and who leave in the countries they are called to direct an indelible mark of their passage.

The Palace of the Government General

We had to appear before this terrible man the day after our arrival; and I beg you to believe that, as we climbed the steps of the side porch which led into his office, my colleagues and I felt very uncertain indeed. I could, but dare not, use a much more intimate and forceful expression which would describe more accurately the intense feeling of fear which gripped us.

When we were introduced to him, I must admit that our initial reception was rather cold. “What are you doing here?” cried the ogre as soon as we crossed the threshold of his office. “I have not asked for you, neither do I have any use for you.” Then, seeing our discomfited expression, he suddenly calmed down and explained that the Collège des stagiaires was about to be abolished and that we had unfortunately arrived in the middle of a complete administrative reorganisation.

We took our leave of him on these good words, especially happy that our meeting had finished. In fact, it was this short interview which decided my colonial career; a few months later, without having otherwise been consulted, I traded my junior professional officer’s stripe for a deputy judge’s hat. Later, I learned to understand and appreciate the “beneficent coarseness” with which we had been greeted; and then I realised that his apparent rudeness hid true goodness and loving concern.

The Palace of the Government General illuminated for a ball

Many years have passed since the colonial adventures of my youth, and over time I have become an old and disillusioned magistrate who is surprised and intimidated by little. Yet even today, when I enter the former office of the ogre in the Palace of the Government General, I still feel a disagreeable frisson creeping across my skin.

On major public holidays such as 14 July or the first day of New Year, or when some prominent person honours our city with his presence, the Palace is decorated to the peak of its dome with illuminations. The doors of its reception rooms are opened wide and all Saigon dances breathlessly until dawn, while lovers of the Queen of Spades crowd around the gaming tables. These balls, known as “ouverts,” are particularly interesting, and it is prudent on such occasions to delay as long as possible the opening of the buffet … and the boxes of cigars.

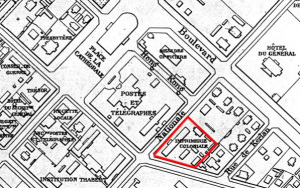

Our Governor of Cochinchina, dispossessed of his palace, had to seek asylum in a large building located on rue de Lagrandière which was originally designed as a commercial museum, and for the construction of which the architect was inspired by the Munich Pinacothèque. Although it was only a poor copy, costly adjustments made it habitable, and it would, in fact, look good too, if the great caryatids flanking the entrance porch did not so miserably disfigure the façade they claim to decorate.

Alfred Foulhoux’s Palais de Justice (1885)

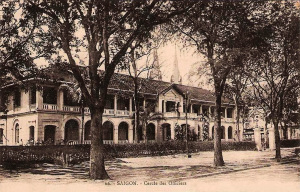

The Judicial Service is housed nearby, on the corner of rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa]. It is very comfortably installed in the Palais de justice, and it may be said that the sober architecture of that building and the perfect harmony of its proportions may be among the most beautiful sights of Saigon. During my early days in the colony, the premises of this important government office, which then existed in its infancy, were infinitely more modest.

The Tribunal once occupied the former Hôtel de la gendarmerie (Police Station). As for the Court of Appeal, it was encamped, after a fashion, in the stores of the Service local on rue Thu-Duc [Đông Du], while the French Chamber held solemn audience in a long hangar which can be admired even today on rue Taberd [Nguyễn Du], near the place de la Cathédrale. The magistrates there had, at short notice, replaced the horses of the gendarmes. The staff of the Attorney General’s Office had been assigned the other wing of these decommissioned stables. It was simple and tasteful. It was here that I was initiated, in around 1882, in the subtleties of native criminal procedure and the mysteries of the modified Penal Code.

Among my new friends was a cheerful fellow, as sharp as a monkey and even more bohemian than clever. Among his eccentric hobbies, he kept some of the most bizarre animals, and he had in his menagerie a cute little honey bear which became the frequent guest of the Prosecution, despite the opposition of the Attorney General, who then had an office in the same building.

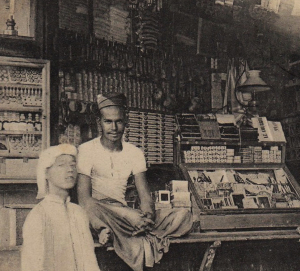

The Justice de Paix

In fact, the Attorney General only honoured us with infrequent visits because he he trusted us, and this confidence was well placed. However, those rare visits, which this excellent man knew how to endow with a very intimate and familial charm, had a serious drawback for us, as they usually coincided with the time we had designated our “cocktail hour” at the nearby café de l’Europe. So we devised a means of guaranteeing the tranquility of these extra-judicial drinking sessions.

Every day, a little before cocktail hour, I was dispatched under any pretext, in my capacity as leading man of the team, to the office of the Attorney General, who always greeted me with his most benevolent smile, and inquired with bonhomie about our health and our work. My reply was of course that all was excellent; but then I would make a discreet allusion to the presence in the building of the honey bear. “What?” the irascible little man would cry, brandishing a huge paper cutter, “He’s brought that dirty beast into the building again?”

That was enough, and it only remained for me to retire with the consciousness of duty done. Upon my return to the Prosecution, the indictments were lightly abandoned, the dossiers quickly rolled up, and our merry band, marching in English style, rushed down to the café de l’Europe where those pernicious cocktails awaited us, covered in snowy ice.

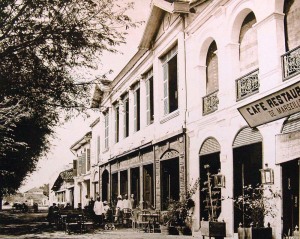

Cafes on the Saigon riverfront

Since I’ve already recounted several old memories, let me just mention one more which dates from the same period and relates to the same subject.

One fine morning, probably taking advantage of the absence of the bear, our mentor arrived in our midst. By the merest chance, he found most of us installed in our rightful places, and painstakingly plunged his nose into the voluminous files which were piled up around us. Only one of the desks remained unoccupied, and for good reason. Its owner, big Robert, had just begun doing exercises, suspended on one of the horizontal iron bars high above the room, and was, at the moment of the Attorney General’s entrance, engaged in some skilful acrobatic manoeuvres.

The arrival of our unexpected visitor caught him by surprise, so big Robert sat above us silently and unnoticed, with his legs dangling down, while we strove to account for his absence. The chief went away satisfied, big Robert nimbly left his uncomfortable perch, and we welcomed his descent with a loud ovation. Thus ended one of the happiest incidents in the life of the colonial Prosecution service.

And what may surprise you most, dear reader, is that our work was no worse for it.

Sadly, most of the actors in these innocent little scenes have long since descended into the grave, and now I live alone with my memories.

To read part 3 of this serialisation, click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](http://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/8641155529_73c760cd0a_o-300x184.jpg)

![L0055713 Cochin China [Vietnam].](http://www.historicvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/8641155529_73c760cd0a_o-300x184.jpg)