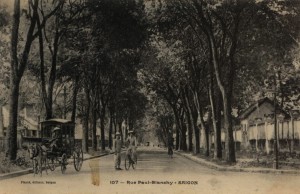

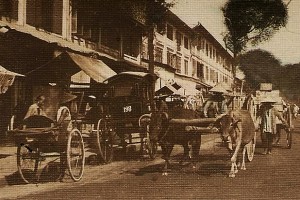

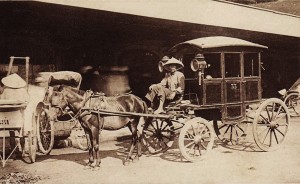

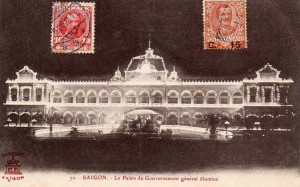

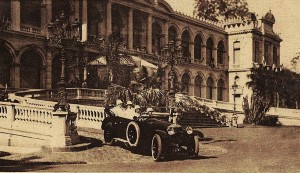

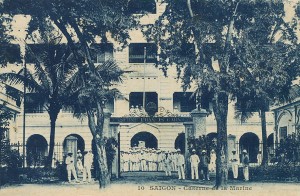

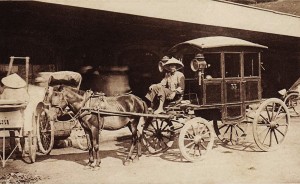

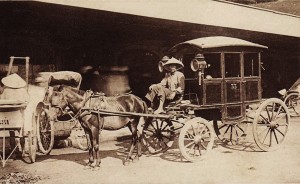

A Saigon taxi rank, late 19th century style

In mid 1888, wealthy French widow Louise Bourbonnaud set off alone on an extended voyage of discovery which took in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Cochinchina, China and Japan. She spent over a week in Saigon and her 1892 book Les Indes et l’Extrême Orient, impressions de voyage d’une parisienne provides us with a fascinating, if somewhat condescending, account of late 19th century colonial life. This is the third of a series of instalments from her book, translated into English.

To read part 1 of this serialisation click here.

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here

Monday 27 August 1888

You can hardly criticise me for spending too much time resting, because I limit my rest to what is strictly necessary and am on the go all day. Also, it’s not even lunch time yet and I am out. It’s good to walk in the mornings or evenings here, since in the middle of the day it is painfully hot.

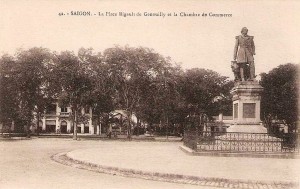

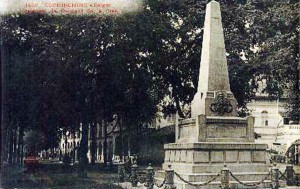

The monument to Mekong River explorer commandant Doudard de Lagrée which stood at the centre of place Rigault de Genouilly (modern Mê Linh square)

I see in the middle of a garden [modern Mê Linh square] a monument to [Mekong River explorer] commandant Doudard de Lagrée.

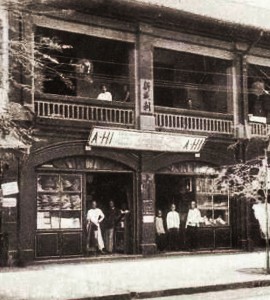

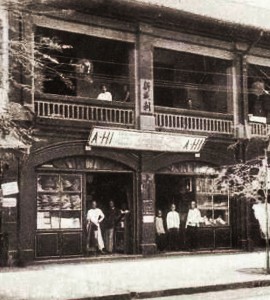

Then, after a few random laps of the city, I find myself in front of the Chinese store in which I did my first shop the other day.

he owner is on the doorstep; he recognises me and greets me kindly. I exchange a few words with him and let him lead me into the store. These “heavenly ones” are traders of the first order. they are thoroughly familiar with the art of attracting and ensnaring the client! I don’t leave without buying a few items, including a Chinese lantern, a rice paper album with a pink silk cover, and a wonderful ivory card holder, decorated with artistically engraved sculptures.

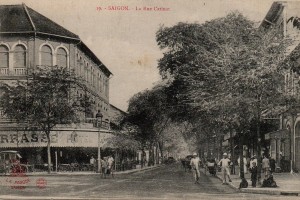

A Chinese shop on rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street)

A beautifully fragrant engraved sandalwood panel draws my admiration, I propose an exchange to the merchant: the panel for one of the white stone figures I bought in Singapore. After ensuring that his big round glasses are firmly fixed on the bridge of the nose, the good shop owner examines the stone figure and, after much thought and discussion, finally accepts my offer. Methinks he got a good deal and that my white stone figure is actually worth several times the price of the sandalwood panel: it had cost me one rupee.

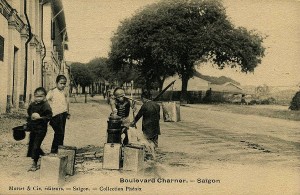

There’s no shortage of vehicles for hire here in Saigon, and I don’t have far to go to find a carriage: there’s a Malabar station near the hotel. But often the horses are not up to the task; many of the poor creatures are not fully grown and have little fat on them. They should definitely eat more straw than barley or oats. This morning fate deals me an unlucky hand; After carrying my purchases back to the hotel, I jump into a waiting Malabar for an excursion around the neighbourhood. But I soon become angry with my Malabar driver because his exhausted horse stops at every corner; the poor thing is exhausted and can no longer walk!

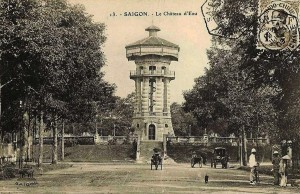

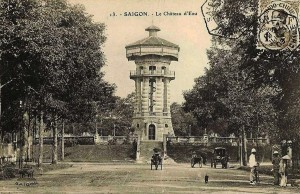

The Château d’eau or water tower which once stood on the Turtle Lake intersection

I stop for a moment to look at the artesian well [the Château d’eau or water tower which once stood on the Turtle Lake intersection]: It is a beautiful work on a very high platform, which features a spiral staircase fitted into a cage. The locals were astonished when they saw the devils from the west take spring water from the ground, I can imagine their amazement!

Now I want to go further, but the poor beast has no desire to continue; it’s impossible to get it to move! Maybe it’s afraid of the buffalo with huge horns which walks past at that moment, led by a young Annamite boy. Such a beast, if it became angry, could throw my little carriage, my horse, my big lout of a driver… even me, up into the air! But the buffalo has a very peaceful demeanour and it seems that it doesn’t want to get angry.

Another view of the Doudard de Lagrée monument

Finally, the horse decides to take a few steps, but it doesn’t take long before it once more grinds to a halt. This time it’s because of a snake, which is leisurely winding its way across the road. Before leaving the hotel, I bought a few pieces of sugar cane that I now chew philosophically. I rather like chewing sugar cane, it’s very refreshing, but the sugar cane here is not as good as that in Martinique, which tasted much better. I offer it to my driver.

I eventually decide to go back to the hotel, because lunchtime is approaching and I also want to get ready for my afternoon visit. Once again, I pass in front of the statue of commandant Doudard de Lagrée, and this time I read the inscription on the pedestal:

Upon reaching our goal,

Death surprises us.

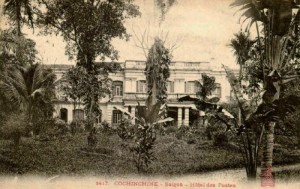

A high-ranking colonial administrator’s residence set in beautiful gardens

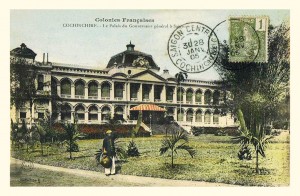

“It’s 3pm when I descend from the Malabar at the house of Mr Céloron de Blainville, Director of Local Services, who comes out to meet and welcome me.

This,” he says, pointing to a large building, “is my office; our residence is a little further on, in the middle of those gardens.” I stop for a moment, amazed at the beauty of the gardens, which are adorned with all the treasures of tropical flora, and then follow my gracious host, who leads me towards his house.

The house that the government has put at the disposition of Mr de Blainville and his family meets all the wishes of colonial comfort. This place lacks nothing, with huge and well-ventilated rooms. In the master bedroom, there are two large beds covered in mosquito nets, a wardrobe, a chest of drawers and several other pieces of locally-sourced furniture. Daylight streams in through six windows, that’s to say there’s no shortage of light.

A salon in one of the larger villas

One thing that surprises me at first is that all the mirrors in the house, without exception, are broken! Of course, I dare not comment on this, but obviously my kind host notices my look of astonishment:

“You find it strange, dear Madame, to see my poor mirrors in this mess! Well, I ‘ll tell you why. My predecessor’s young son had a mania – I dare not qualify it as innocence – to break mirrors! Of course, each takes his pleasure where he finds it, although I confess that I really don’t understand that particular pleasure. Anyway, I hope that all the damage will soon be repaired, and be assured that my own children certainly do not entertain themselves in this way!”

I walk successively through a nursery, a huge living room with two chandaliers hanging from the ceiling where official balls and other events are held, a large dining room furnished with carved furniture, and finally a bathroom with a bath big enough to accommodate four people – more like an indoor pool!

The exterior of a colonial administrator’s residence

A wide verandah runs all around the house, keeping the ground floor rooms free from excessive heat.

Hidden behind clumps of greenery are staff accommodation, stables and garages where my hosts keep their fleet: horses, two carriages and a staff to match. It seems that before they arrived here the de Blainvilles had not expected to be offered such a comfortable arrangement, so they are delighted with their position – as one would be! Mrs de Blainville, who joins us and is a most gracious hostess, welcomes the fact that her dear children will be able to learn to ride a horse and drive a carriage.

As part of their contract, my friends are supplied at no cost with table linen, kitchen equipment (including pots and pans) and many other household items. What a saving! They aren’t even responsible for breakages, but on one condition – that that they keep the broken pieces to show to the finance office. Then the objects are immediately replaced. Fortunately, the expenses budget will cheerfully pay for mirrors broken by a terrible child, since there is nothing easier than to show the pieces!

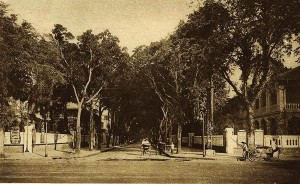

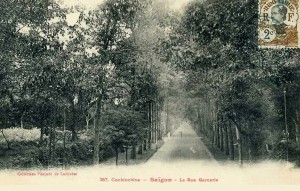

Rue Garcerie, now Phạm Ngọc Thạch street

Mrs de Blainville sends her two youngest sons to change a banknote at the Résident-Général’s office. But the children are somewhat slow to return, and the mother becomes very concerned and starts to imagine that someone has kidnapped or killed her children! She begins to cry, and I try my best to reassure her. Finally, the two boys return home, bringing the money they fetched… and no one has said a word to them on the road!

I think that back in Paris, people don’t have a very fair idea of the colonies. Certainly, there are some colonies which cost the Métropole a great deal of money, but for a long time now, thank God, Cochinchina has not been one of those! The best proof is that each year, Cochinchina contributes I do not know how many millions towards the expenses for the occupation of Tonkin [Northern Việt Nam]. In order to have colonies which spread our influence far and wide, we must be prepared to make some small – even large – sacrifices. France has never balked from this, and now she begins to reap the benefits.

A malabar awaits customers

I pass several hours with the charming de Blainville family, hours which will never fade from my memory, and I thank heaven for letting me get to know such good friends. Everyone, young and old, gathers around me, monopolises my attention and makes pleasantries. It takes all my strength to accept a gift of a Chinese book which the youngest son wants me to have.

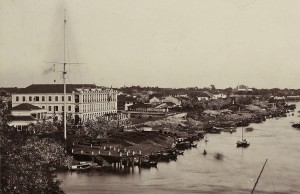

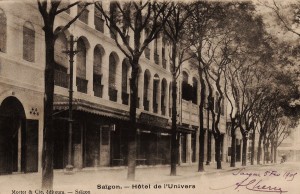

I return to my hotel, still moved by their spontaneous friendship. The manager gives me two newspapers: Le Saïgon and l’Indo-Chine; the first costs 12 cents, that is to say, 60 centimes, and the second 15 cents, equivalent to 75 centimes! We cannot say that the press here is cheap! However, these papers are still interesting; they give the news from Europe, America and Australia; the movement of the port, including the arrival and departure of ships and commercial vessels; notices of auctions; and theatre reviews. For six months of the year, a French theatre company gives performances here which attract a strong following.

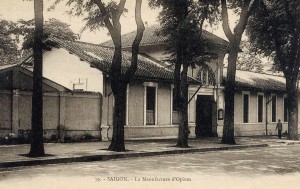

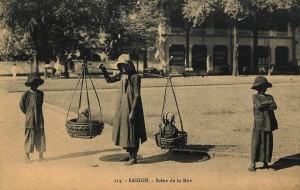

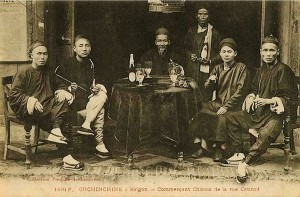

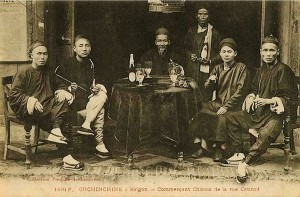

Chinese merchants on rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street)

Tonight, the thought comes to me that my birthday passed three days ago and no one thought of sending me good wishes. Poor Louisette! That’s what it means to set off around the world on your own!

To distract me from this sad thought, I look out of the window at my industrious neighbours, who have for a moment interrupted their hard work to eat their frugal dinner. I see them clearly, squatting on their mats in the back of their shop, the very large door of which at that moment is open to allow the cool of the evening to make itself felt. They pick with their chopsticks at something I can’t recognise from this distance; but I think it’s meat – something extra, then!

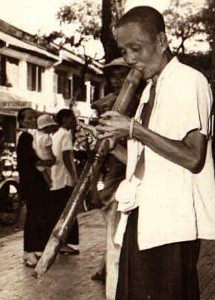

Their lighting is quite modest, consisting of a small oil lamp. Today the use of oil lamps is quite widespread in the Far East and there is hardly a remote village which doesn’t have several. All the same, I still wonder how the local workers can see enough to continue their work in the evening, not to mention what they did in days gone by when all they had was primitive candle light.

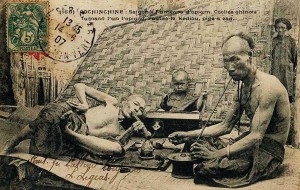

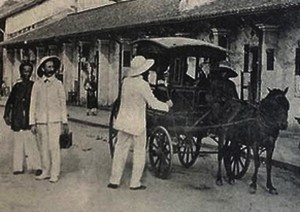

Malabars on rue Catinat (Đồng Khởi street)

In front of the hotel, several Malabars are parked, waiting for clients, but gradually the hubbub of the evening diminishes and calm is restored. I sit on the verandah, overlooking the inner garden of the hotel. Lizards come and go silently, catching mosquitos as they pass. They are welcome to eat these horrible little wild beasts that feed on human blood!

The evening breeze has cleared the sky and the stars twinkle merrily up above!

Tuesday 28 August 1888

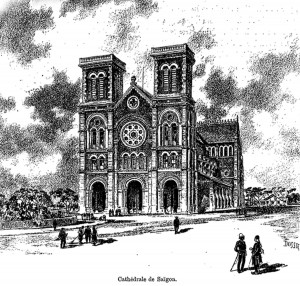

This morning, it’s not so hot; the sun is nowhere to be seen in the sky and the breeze blows strongly from the river, laden with salty flavours. I’m certainly not complaining about this fresh weather, and in the morning, I pay a visit to the tomb of the bishop of Adran, who was the friend of the Emperor Gia Long and who died at the end of the last century.

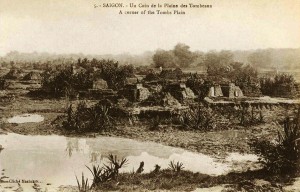

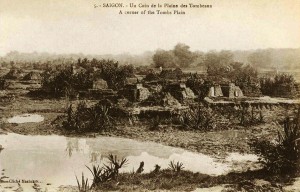

The Plaine des tombeaux (Plain of Tombs), a vast burial ground which once covered large parts of modern Districts 3 and 10

I go by Malabar, as usual, first taking the road I followed the other day to go to Cholon, passing a plain covered in tombs. Some of these tombs are centuries old; several are decorated with carved dragons or grimacing figurines. Ivy or grass covers them all and gives the countryside quite a melancholy look. My driver jabbers a little in French, and, as he seems a bit smarter than his colleagues, I manage to draw some information out of him.

This factory we are passing is a sugar factory; my driver tells me that it belongs to a rich proprietor who owns 200 houses and has a fortune of many millions. I wish this unknown gentleman well, but I remember the old saying in my country: Do not believe half of what people say.

A little further on we pass an ice factory. There is no need to emphasise the importance of ice as an object of daily consumption in this fiery climate.

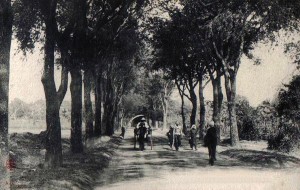

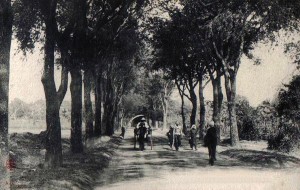

The route coloniale leading west from Saigon

The land on this side of the city must be a bit higher, because there are no rice fields alongside the road, which is lined with large trees.

We arrive at the race course [the original one located in the area south of the modern Saigon Railway Station], where civil servants and military officers come to lose their piastres and the locals their sapeks. Annamites have a much more developed passion for gambling than us and they never miss an opportunity to bet.

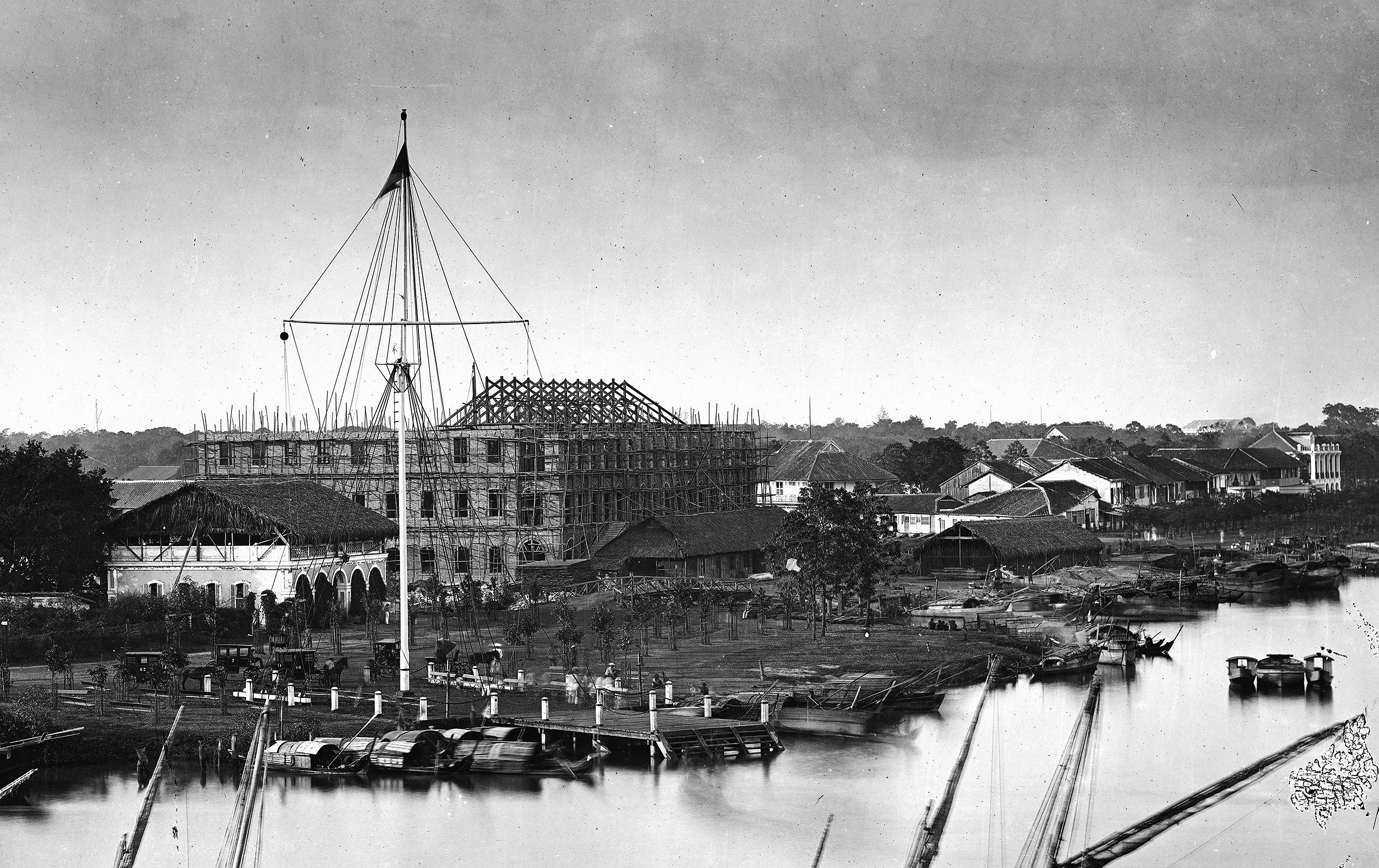

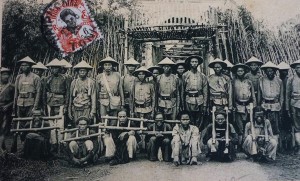

Then the car stops at what in France we would call a level crossing; Needless to say, barriers and gatekeepers are absent. Fortunately, members of the public deputise, and we wait for a train to pass before crossing the road. It’s not a real railway line, for that kind of transportation is lacking in these parts; it’s a Decauville line which works in the service of the army. We have arrived at a military installation [the Nouvelles casernes d’artillerie coloniale or New Colonial Infantry Barracks, which after 1954 became Camp Lê Văn Duyệt, headquarters of the Third Corps of the ARVN], everywhere can be seen signs reading Terrain appartenant à l’armée, Terrain de l’artillerie, etc. We see only barracks, and those Annamese riflemen with their chignons and plate-hats.

The tomb of Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran

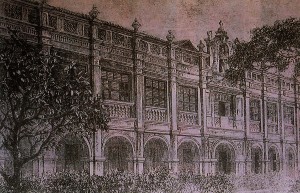

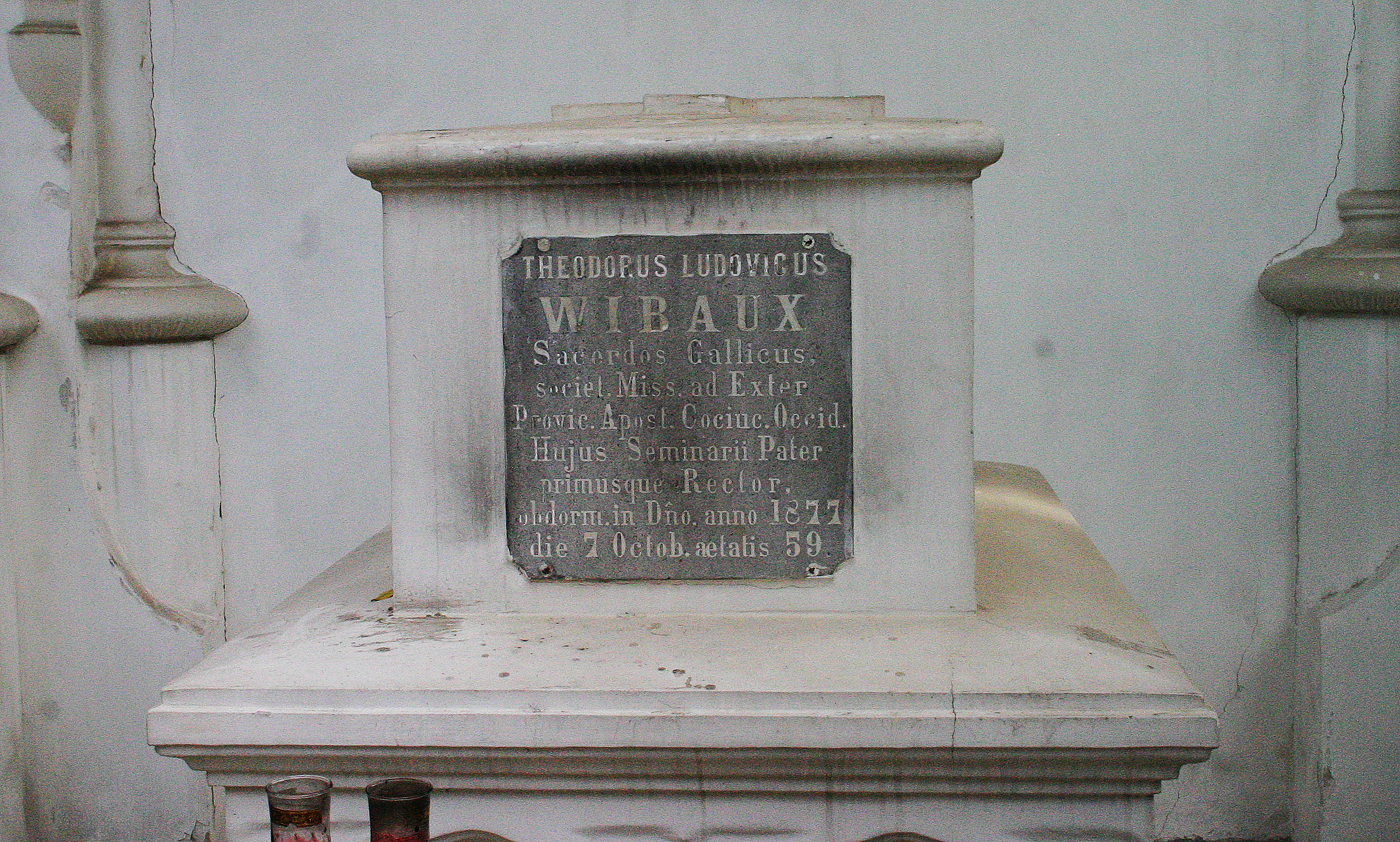

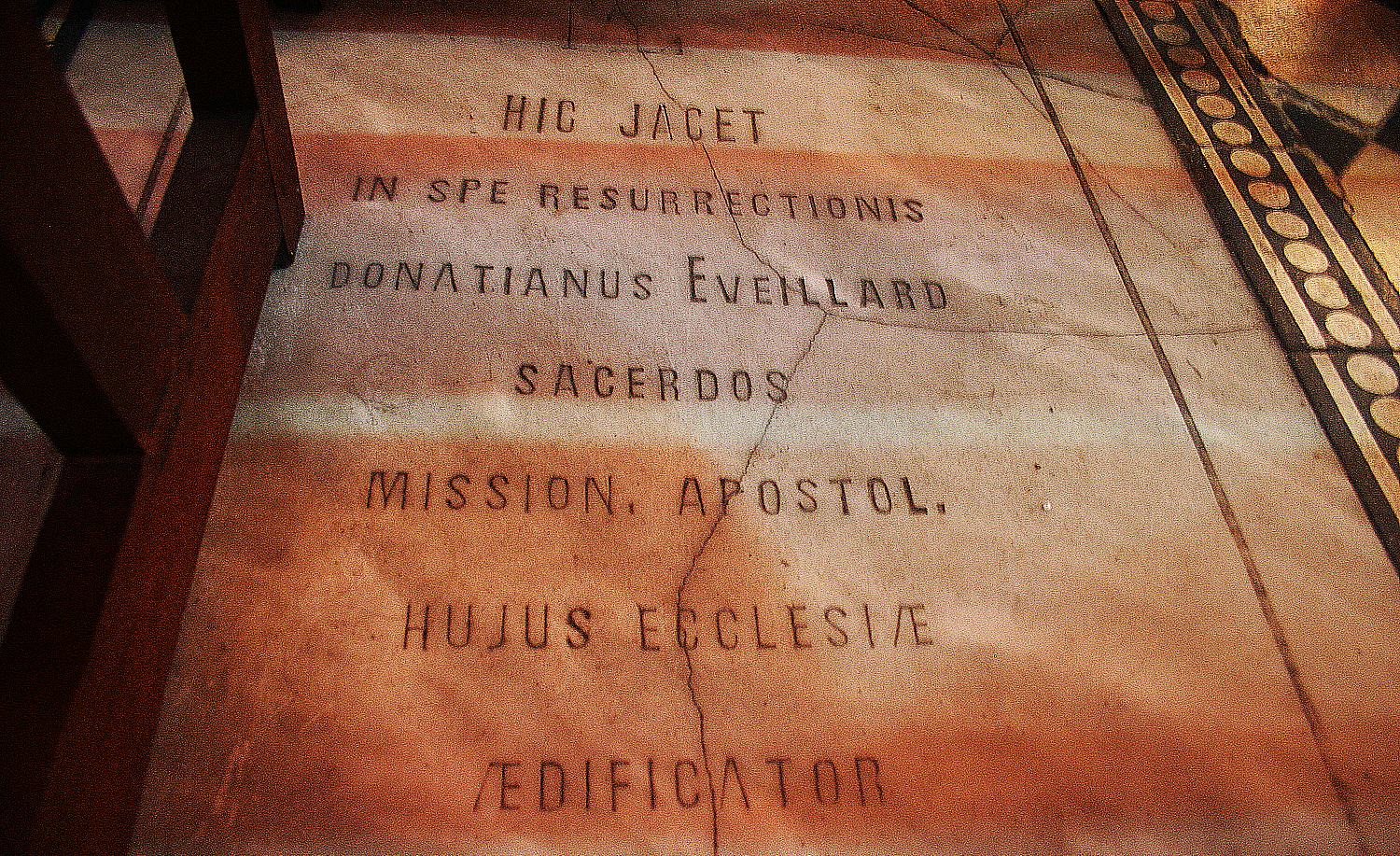

Eventually, we stop in front of the tomb of the bishop of Adran [see also the article Lăng Cha Cả – From Mausoleum… to Roundabout!] ; it is located in the middle of a small cemetery, the main gate of which, built in the local architectural style, resembles the entrance to a pagoda. The tombs in the cemetery belong solely to Catholic priests, some of whom died in Cochinchina, others in Annam, Tonkin and Cambodia, and whose remains were finally transported here. The tomb of the bishop himself is located in the centre of a grand mausoleum and is without inscription; two other tombs are placed to the right and left.

It was towards the beginning of the 17th century that the first Christian missionaries penetrated into Cochinchina, where they were well received at first, both by the population and by the authorities. But besides the purely dogmatic precepts, the newcomers also brought with them some ideas which completely contradicted those followed for centuries and centuries by the governors of the country. Conflict and persecution followed. There is a long list of those who paid in blood for their faith on these distant shores, paving the way for the future triumph of these broad and fertile ideas, which the flag of France has always sheltered beneath its folds.

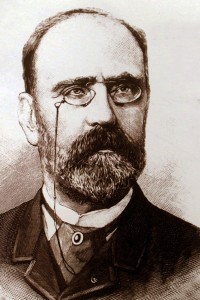

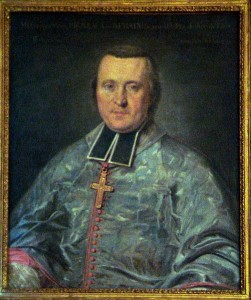

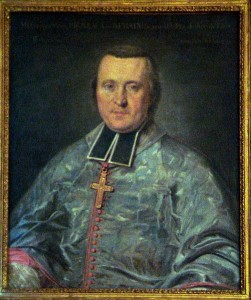

Pigneau de Béhaine, painted by Maupérin during his 1787 trip to Paris with Crown Prince Cảnh, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society

At certain times, however, intelligence reigned in the relationship between the government and missionaries.

The Emperor of Annam, Gia Long, owed to Monsignor Pignaud de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran, first his life and then his crown. Driven from the throne by competitors, the prince took refuge with the bishop and later, with the support of several French officers brought into Annam by Monsignor Pignaud, Gia Long was able to defeat his enemies, retake the throne and reorganise his kingdom. It is from this period that all the large defensive fortresses and citadels in this country date, and which were constructed according to the principles established by Vauban.

Gia Long did not forget the services which had been rendered to him; French officers, collaborators in his restoration, were showered with honours and distinctions and the bishop of Adran continued to have a considerable influence on the mind of the Emperor. On the death of his friend, this wise and prudent counsellor he had valued and worshipped, Gia Long arranged a beautiful funeral and raised this tomb, which is now a place for excursions and promenades for the inhabitants of Saigon.

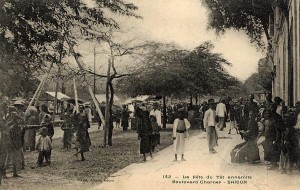

Malabars on boulevard Charner (Nguyễn Huệ boulevard)

Before I leave the cemetery, I give several sou to the boy who opened the door for me; I am guessing that these coins are not commonly used here, because the little boy was delighted with them.

Here we go again! The driver wants to return, because, he says, his horse is tired. That is possible, but if the poor beast was better nourished, it would be stronger and would not be so exhausted after such a short trip.

It seems that, among the Malabar drivers of Saigon, I already have a reputation as a killer of horses (!) by making trips which, in their opinion, are too long. Yesterday, I asked a driver to pick me up at the hotel, but he was unwilling to do so. This one had a good horse, and that’s why I wanted to use him. He had probably talked to a colleague, who deterred him from the rendezvous.

I end up insisting that my driver should continue, but achieving this is not without difficulty. I promise him another piastre and he accepts only after much discussion. In addition, I must consent to let him go and change horses first. I agree, and afterwards we return to Cholon along the banks of the arroyo.

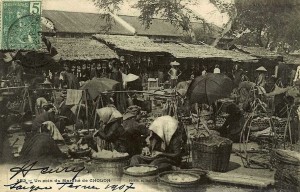

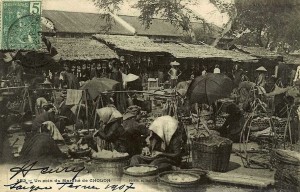

A corner of the main market in Chợ Lớn

What activity prevails here, everyone is rushing around ! There are all kinds of factories and merchant businesses. In one shop, I see a carpenter making coffins of sandalwood, this wood which smells so good, and to my amazement, I notice that one side of the coffin interior is lined with a mirror! What a strange idea! What is it for? Surely the dead do not need to see their reflections!

I buy some more pieces of sugar cane to eat on the road, as that is quite the custom here, and one which pleases me very much, as I’ve said previously.

As in Saigon, the various industries are gathered in streets which specialise in particular trades. I walk along the rue des des Ébénistes [now Trần Tường Công, District 5], where cabinetmakers’ shops are pressed one against the other. Here may be found skilled designers of a thousand trinkets for which European and American tourists compete with offers of bank notes. If one wants to get caught, one can easily buy too many things here, as at every step there are wonderful pieces of exquisite workmanship, for sale at relatively low prices.

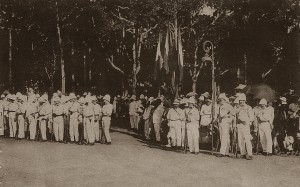

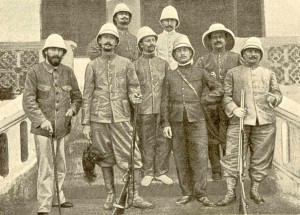

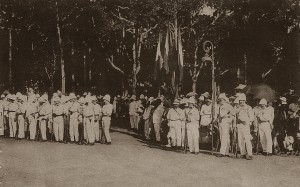

Colonial soldiers gathering for a ceremony

One thing not lacking in Cholon is the military; they are everywhere; it is true that the barracks are not far apart, and for the soldier, it is a pleasure, because when he is on leave, he can stroll here amongst the crowd. In Cholon there is so much to see and the soldier’s or sailor’s every wish is served to perfection. Army and navy personnel fraternise here, raising their glass to the health of their distant country, dear France, which they left with enthusiasm and which, alas, more than one of them will never see again.

I return along the same road by which I had come, this beautiful road bordered with tall trees, whose shade is so good.

I pass the Chinese cemetery at the side of the road, in front of which is a wall with a large door in the middle; but at the two sides and at the rear it has no wall whatsoever! This is an economy I can’t understand! It reminds me of the churches of some pueblos in South America, which consist of a large decorative stone wall and, behind it, a small mud hut.

A mandarin’s tomb

The dream of every Chinese person is that after his death his remains will be laid to rest in his native land, but it should not be assumed that everyone can realise this wish beyond the grave. For a rich Chinese, there is no difficulty: when he dies, his body is buried here temporarily and later, under appropriate conditions, shipped to Canton or elsewhere. But for a poor Chinese, things don’t go quite the same way. The deceased is buried here permanently, as no one has the funds to pay for a post-mortem journey. In this way, he is left until the last judgment in the place where he passed from life to death.

On the road I pass a group of carriages in which several mandarins are seated; these are judges who look very serious and seem to have a very high idea of the functions vested in them.

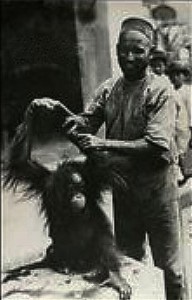

Returning to Saigon, I take another promenade in the Jardin des plantes, admiring again the tigers, lions and bears and also seeing an animal which I did not see last time: an orang-utang, or “man of the woods,” if you want to translate these two Malay words. Oh, what a monkey! It’s the size of a man, but with longer arms and stronger hands; its head is huge and its face is beardless, while its whole body is covered with long hairs.

An orang-utang in a colonial zoo

The orang-utang has a large broken tree branch in its cage. It stands against the wall and climbs as high as it can go, then drops down, to the delight of the spectators, who let fly at the animal with all sorts of comments, which hardly seem to bother it. What interests the animal more is the zookeeper who has just arrived with a glass of beer. The orang-utang, which is no doubt very familiar with the procedure to be executed, arches its back and opens its mouth, into which the man then slowly pours the beer, which the consumer seems to appreciate.

A large audience has gathered to watch this little scene: Chinese and Annamite rub shoulders with Malabar. Malay, Japanese and French, as all the onlookers share their thoughts with each other in a heterogeneous language where grammar and syntax have no place.

As I leave the Jardin des plantes, my Malabar driver starts his whining again: “My horse can do no more! It cannot go further! The poor beast is half dead!” Conclusion: We must go to the stables. There is, of course, another conclusion, and that’s that I pay a supplement to keep going, and I think that’s what my tricky looking driver wants. But I don’t let him cheat me this time, and since the horse is tired, we return to Saigon.

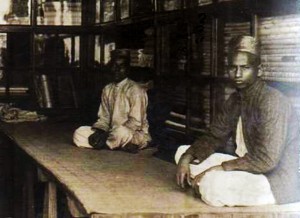

Chettyar traders

We pass a village inhabited almost exclusively by Indians. It is clear that we are in the presence of a different race. The men are tall and slender, with beautiful eyes; they arrange their hair in a coquettish fashion and lovingly look after their teeth. These Indians would never think of chewing that awful betel! Their hair hangs down to the middle of their backs, or they tie it up in a small chignon.

The Indian women are also very attractive; I had the opportunity to observe their deep, soft black eyes during my trips to British India and later to French Pondicherry.

These Indians are beautiful living statues, worthy to serve as models for our artists, sculptors and painters, and whose forms, copied with talent, can appear honorably alongside the masterpieces of antiquity.

To read part 4 of this serialisation click here

To read part 5 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.