Louise Bourbonnaud

In mid 1888, wealthy French widow Louise Bourbonnaud set off alone on an extended voyage of discovery which took in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Cochinchina, China and Japan. She spent over a week in Saigon and her 1892 book, Les Indes et l’Extrême Orient, impressions de voyage d’une parisienne, provides us with a fascinating, if somewhat condescending, account of life in late 19th century colonial Cochinchina. This is the first of a series of instalments from her book, translated into English.

Friday 24 August 1888 – Arrival in Saigon

Cap-Saint-Jacques [Vũng Tàu] marks the entrance to the Saigon river. A beautiful lighthouse, built at the end of a rocky and wooded promontary, sends its light up to 30 miles out to sea; opened on 15 August 1862, this lighthouse stands 139m above sea level; the tower itself is 8m high.

The Cap-Saint-Jacques (Vũng Tàu) lighthouse

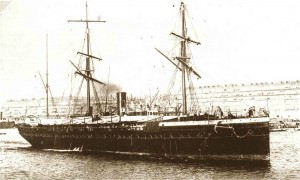

The mouth of the river is wide and there is enough water to allow larger ships to continue as far as Saigon; the trip takes about six hours, during which we continue to navigate through the countryside. Rice fields and clumps of trees follow one another in quick succession and delight the eye; the river is covered with local craft, among which the [Compagnie des Messageries maritimes vessel] Ava stands out majestically, like a giant among pygmies.

How beautiful it is here! I never tire of admiring it! And more than being a beautiful country to us, it is also a corner of my beloved France, where I’ll stop for a while amongst my compatriots. Most of the passengers are up on deck, watching and admiring the scenery, like me. And amongst them is a Prussian, who is smoking a large pipe. I take this opportunity to make the observation:

“It is clear that we’ve arrived in French territory, where we can breathe an air of cleanliness that is not encountered in the colonies of other nations.”

The Prussian pretends not to hear and – appearing to do so deliberately – rudely sends a puff of smoke from his good porcelain pipe in my direction.

I sneeze two or three times, while the rude person goes away without saying a word!

The Compagnie des Messageries maritimes steamship Ava, pictured in Marseille

The Ava continues its journey. From time to time, we pass small “boat garages” formed by rows of stakes driven into the river, where house boats are sheltered. These Annamite [Vietnamese] boats have a characteristic appearance: the middle sections have a canvas cover and at each end is a platform where the person responsible for manoeuvring the boat stands – and it is noteworthy that it is very often a woman who carries out the task of pilot.

Lower Cochinchina is an alluvial country, a flat region, all the southern part of which is formed by the tributaries of the Mekong, lands driven by the current of the great river, then pushed by the tides and definitively fixed by the vegetation, which is rich here, as in all the inter-tropical countries, thanks to the constant humidity and the heat of the sun. Lowlands and swamplands are often impassable on foot and the villages would remain isolated from each other if the country was not criss-crossed everywhere by canals – known here as arroyos –which serve all communications. Travellers, food products and goods of all kinds circulate almost exclusively along the network of waterways which bifurcate to infinity, serving smaller population centres. It follows from this fact that the inhabitants of Lower Cochinchina live on the water, or rather, half if not more of their existence takes place on the water. There are even families of boatmen whose members are born and die on the water, setting foot only rarely on the mainland.

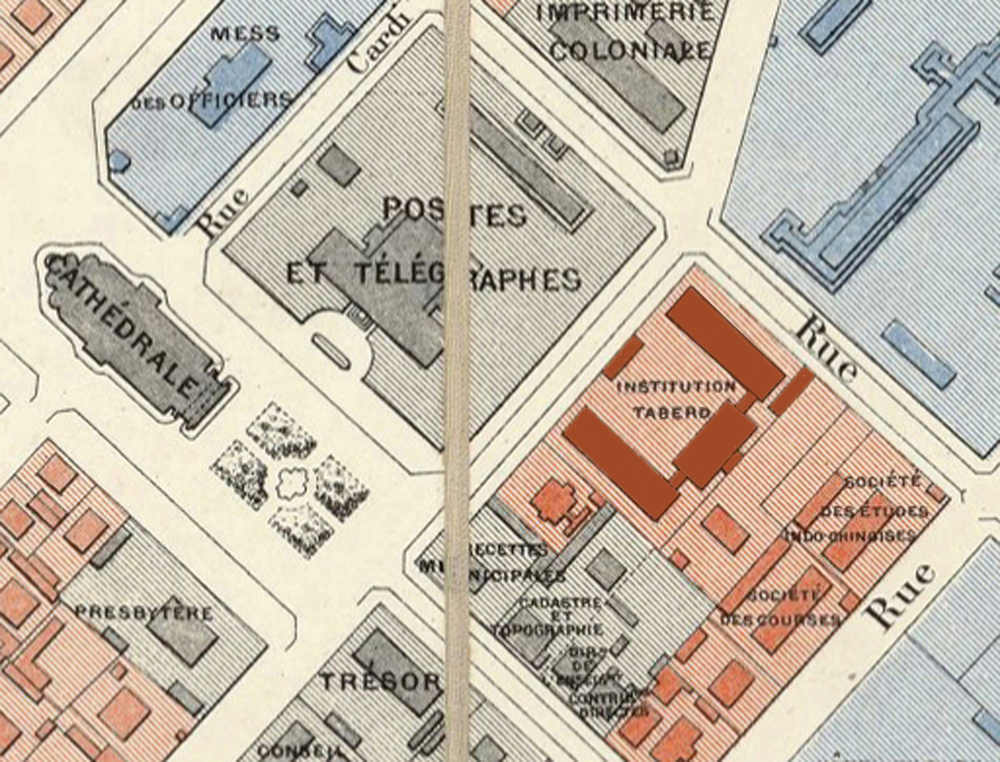

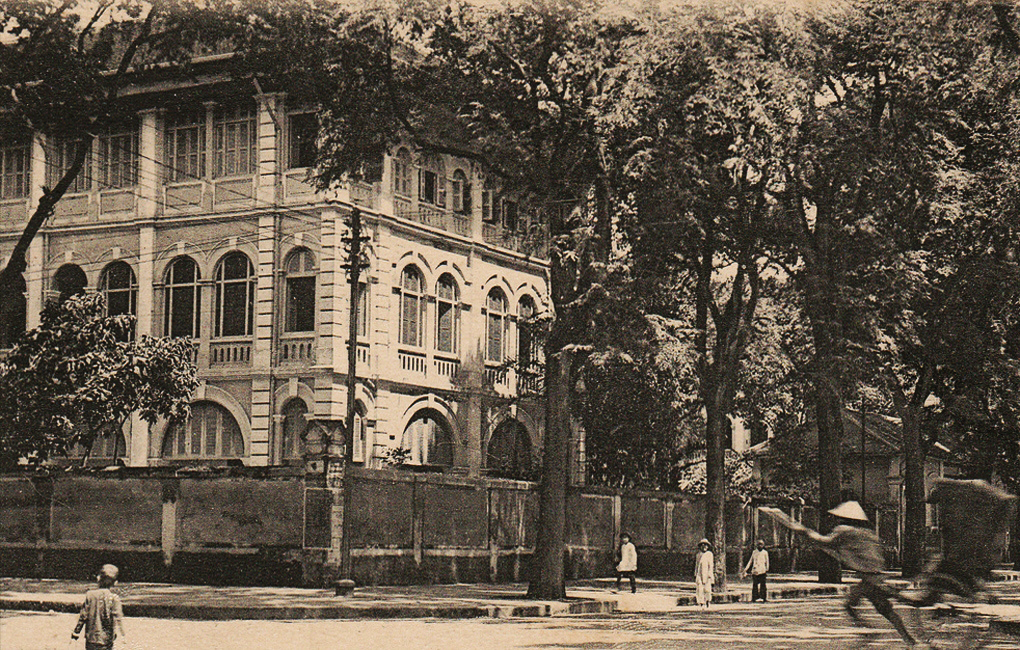

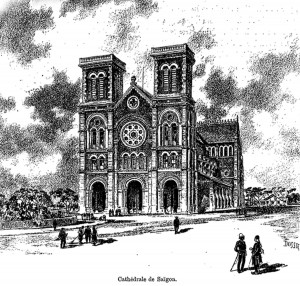

The Saigon Cathedral before its spires were added in 1897

Among the trees along the shore, bands of monkeys play. By now they are probably very familiar with the sight of steamboats, and they grimace at us as we pass.

A full hour before we reach Saigon, we can see, over the greenery the two towers of the Saigon Cathedral in pink brick; and it is not a little curious spectacle, the appearance of this European monument in an ultra-Asiatic milieu.

We’ve arrived. The Ava docks, Annamite boats surround us and their boatmen rush to offer us roast chicken, bananas, oranges and mangoes; I say “offer,” but it’s a euphemism as you have already without doubt understood. However, there’s not too much reason to complain, because the prices they charge do not seem to me to be exaggerated.

However, there is a category of indigenous trader of which it is necessary to be slightly wary: the type which offers to change your French money against the piastre, which is used exclusively in Cochinchina. On the arrival of each vessel, as the rate of the piastre is very variable, this results in a small trade of speculation where the game is to maximize the benefit of the newcomers’ ignorance regarding the current exchange rate.

A steamer docks at the Messageries maritimes quayside

Among those who come to us offering their services are shoemakers and tailors; the latter are the most skilful of all, and, as long as one provides them with a model, they can run off an article of European clothing as well as any of their colleagues back in Paris.

The family of my travelling companion Mr X comes to bid me farewell; now is the time to disembark. On the quayside, a carriage of the Messageries is parked; it is loaded with bags of letters; how many brave troopers will find therein news of their dear France!

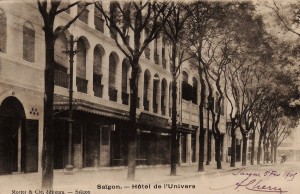

Four other carriages driven by soldiers wait for the family of Mr X, passengers and luggage. Finally my turn comes: the porters grab my bags and transport them ashore. By car to the Hôtel de l’Univers, one of the best known hostelries in Saigon!

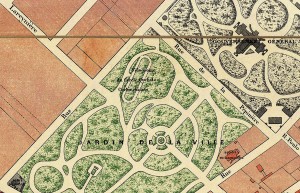

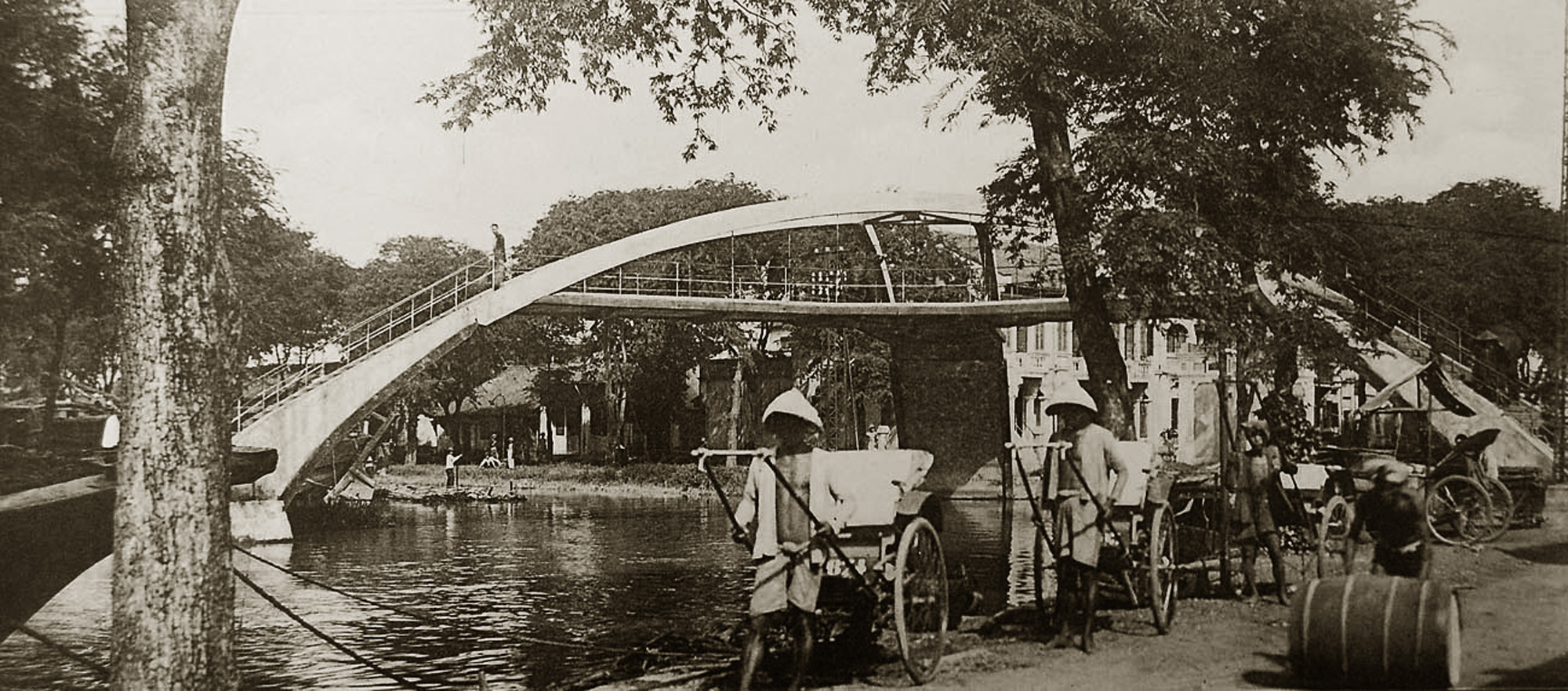

The hotel is some distance from the quay where we disembark from the ship; I cross a river on a beautiful bridge [the Pont des Messageries maritimes], but before we get to our destination, the road passes through the middle of a marshland where Annamite huts stand on stilts.

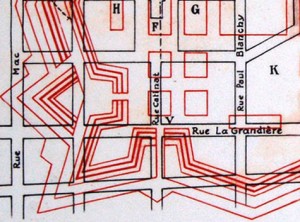

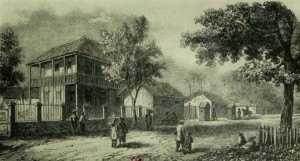

The Hotel de l’Univers on rue Turc (now Hồ Huấn Nghiệp)

At the Hotel de l’Univers [on rue Turc, now Hồ Huấn Nghiệp], I check into a suite comprising two rooms on the first floor. I have at my disposal a beautiful bedroom with a large veranda, or rather a large covered balcony which overlooks the courtyard, in the middle of which stands a small garden.

The other room has two windows which overlook the street; it is furnished with a dressing table, a writing desk, a sofa and three side tables. We are here in a civilised country, and the place is not lacking in any way, particularly when it comes to hotel staff, because I have at least half a dozen attached to my person. Some sweep, some dust, others do nothing and the remainder seem to be there to help the latter! This is the division of labour (?) In all its beauty! But as I’ve said, these brave employees are cheap: a handful of rice and a few sous are quite enough for them, so we can afford to pay little for the luxury of a large staff.

Taught by experience, I begin by installing the mosquito net. We must be on guard against these little enemies of the night, and as I have to spend the next few days here, I hope that my rest will be disturbed to the least possible extent by them.

By 10.30am, everything is pretty much in order in my room, so I decide to go for a tour of the city, pedibusse cum jambisse, to speak the language of the illustrious Tartarin [Alphonse Daudet, Tartarin sur les Alpes]. But I don’t go far this time, because I immediately stop in front of an antiques shop and decide to do some shopping.

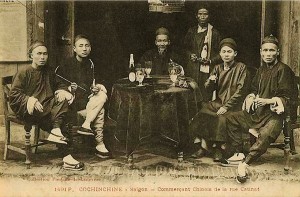

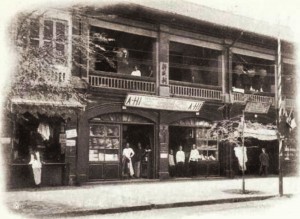

Chinese shopkeepers on rue Catinat

And my goodness! Encouraged by the range of goods and the cheap price, I buy successively: a pair of 1m high Chinese vases, a Japanese junk made from ivory, a Japanese table, some photographs, a sword in a carved sheath, watercolour landscapes on rice paper, an ivory bust, and finally a small box containing Chinese eating utensils; in it there is a knife, a toothpick and two small implements with which the “Heavenly ones” transfer the rice from the bowl into their mouths with a dexterity that has never been possible for me to imitate, despite numerous attempts.

The bill does not exceed 80 francs, that’s nothing! I am sure that in Paris I would not pay less than 600 francs for these objects! It is true, however, that there will be customs duty to pay and that, on getting back to France, I will be asked for a sum greater than that of the purchase itself.

“Send these objects to me at the Hôtel de l’Univers,” I say to the dealer as I leave the store.

And immediately four Chinese pick up the vases and trinkets and set off in single file in the direction indicated.

I follow them and arrive almost at the same time. My purchases are deposited in my room and I tip the porters: one franc between them, five cents each, this is a fantastic tip which they can hardly be used to, judging by the warmth of their gratitude! These 25 centimes must be equivalent to a countless number of sapeks!

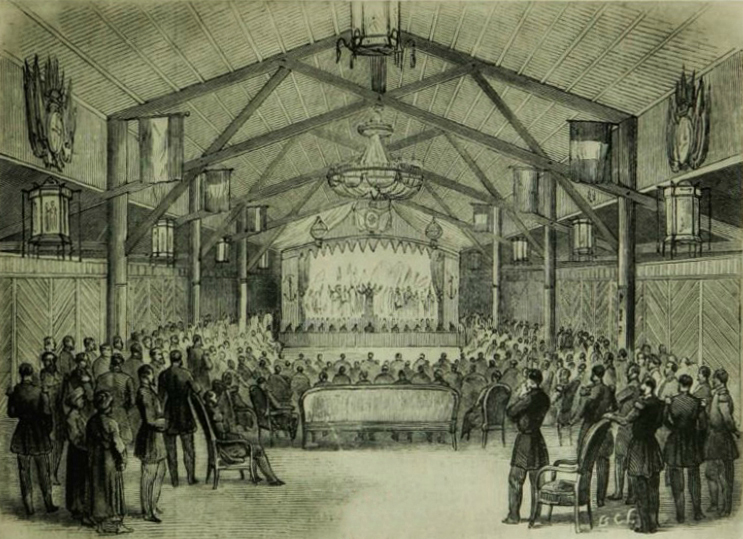

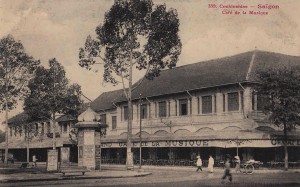

The Hôtel and Café de la Musique

While waiting for lunch, I stop to talk to the manager of the hotel and tell him, among other things, that a passenger on the Ava strongly suggested to me that I should stay at the Hôtel de la Musique, located in front of the square, and not the Hôtel de l’Univers.

When I describe to him the gentleman who gave me this advice, the manager laughs:

“I know who that is, Madame,” he says, “I recognise him perfectly; that’s one of my old customers who caused me all the trouble in the world when I tried to make him pay back a small sum he had owed me for a long time. And even now I’ve still only recovered a part of my money! Ah! I fully understand why this gentleman did not recommend that you stay in my hotel! I do not want to speak ill of my colleagues, but when you leave Saigon, I hope to hear you say that nowhere else in this city is better than the Hôtel de l’Univers!”

A bell rings. To lunch! The dining room is large, the punka fans work, the fare is good, the service excellent. There are at least 30 waiters who are constantly coming and going, each of them carries in his pocket the lunch menu and, before each dish, they pass it in front of every guest’s eyes. The drinking glasses are enormous, never before did I drink from glasses as large; this is probably because of the chunks of ice that we hasten to replace as soon as they are melted.

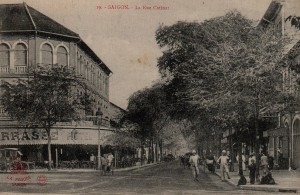

A scene on rue Catinat in the late 19th century

Veal stew, macaroni au gratin: this is the menu for my first meal in Cochinchina. No local colour, as we see. But be patient! It will come.

The dessert is varied and includes mangosteens, for which I have a decided weakness. Coffee is served with cognac; then they present me with a bottle of rum and some sugar. So much strong liquor at lunch time!

Silently, thanks to their thick felt soles, the waiters circulate around the table, some bringing clean plates and full dishes, others removing dirty plates and empty dishes, without the former ever encroaching on the functions of the latter. There is never any confusion of responsibilities here and everyone knows the limits of his duties.

And what a serious look on the faces of these brave people!

Saturday 25 August 1888

My principle, while travelling, is that I don’t waste time. I’ve come thousands of miles to see and I can’t wait to see. Also, I do not stay long in each place and so, immediately after landing, I like to run here and there, notebook in hand, noting in passing my impressions. I have already seen many things in my long travels, but the new always attracts and seduces me, and I can’t resist the pleasure of seeing it again and again.

I saw North America, I travelled from east to west, from north to south; I saw the lush Antilles, land of pineapples and languorous people; I visited South America and I recorded, in a previous volume, the story of these trips. I should therefore be rather blasé about the various spectacles offered to Europeans by countries that are totally different from ours in manners, customs, habits and ways of life.

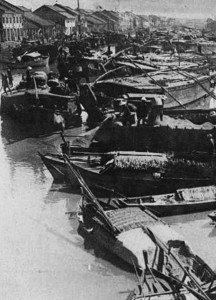

Merchants vessels on the arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé creek) in the colonial period

Well, no! I never tire of looking around me; of observing all aspects of this world which are strange to my eyes, people who move and think in a different way, live differently than we do and to whom our customs must also be a matter of astonishment. It is true that if the Oriental is surprised about something, he usually betrays nothing and maintains an air of apparent indifference.

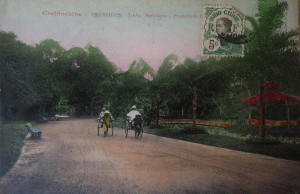

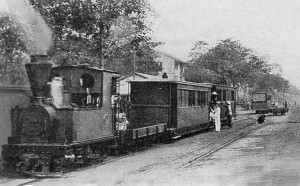

This desire to see and to see immediately, this impatient curiosity, so natural in a traveller, is such that just half an hour after lunch, I decide to go by carriage to Cholon, the important suburb of Saigon. What am I saying? To the great and commercial Chinese city on which the capital of our beautiful French Cochinchina depends!

Even before visiting Saigon, I wanted to make a small excursion to this place, which I had heard was an entirely Chinese city and very curious to see.

Thanks to the kindness of the manager of the Hôtel de l’Univers, the guide for my walk is a Pondicherry Indian, whom I credit with experience and local knowledge.

Cholon is four or five miles southwest of Saigon, on the banks of the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé Creek].

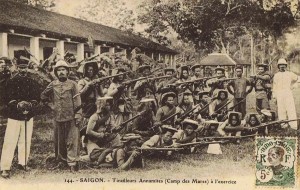

The road I take – slowly, while looking at everything along the way – gets me there in about an hour. Half way along, we pass the Gendarmerie nationale and Caserne des tirailleurs Annamite [Vietnamese riflemen’s barracks].

Vietnamese riflemen at the Camp des Mares barracks

Here are the brave soldiers who have rendered services to us in Tonkin! I doubt that they would compete with our handsome cavalrymen, our dapper hussars, our sprightly infantrymen or our brave zouaves [French North African light infantrymen]. But, such as they are, they are still very useful to us, and we need to know how to appreciate their true value.

These little soldiers look very odd. Their costume consists of trousers and a navy blue jacket with a red ribbon garnish at the back. Their hair is wound in a chignon and above it they wear a tiny hat-shaped plate with a small pointed tip in the middle: the salacco.

What disfigures them is their messy habit of chewing betel. All have black teeth and bloody lips, and they keep spitting out long streams of reddish saliva. It seems that here, the idea of supreme beauty is to have black teeth! It’s the case to say: Each to his taste. Because, know it well, these brave Annamites mock Europeans whose white teeth, they say, look like dogs’ teeth, and they would not for the world enter into relations with the toothbrush, tooth powder or Eau de Botot [mouthwash]!

In the field, I see a lot of mounds, some of which are topped with stones, but most of which are covered with grass: these are the local people’s tombs. We know that in China it is the custom to bury the dead alongside the roads; in fact, that is how we proceeded in ancient times in Europe. Here in Cholon, the Chinese population dominates. In fact, whatever the country they are located in, the Chinese do not like to change anything in their habits and especially their traditions, the origins of which are lost in the mists of time.

The Chợ Lớn creek

I was struck, when I entered the Saigon river, by the animation that reigned there, due to the large number of boats. But all that is nothing compared to the scene on the arroyo de Cholon; here the junks are countless, the eye can’t distinguish one from the other, so they all seem entangled together along the banks…. and those banks themselves are lined with huts on stilts which plunge into the river; the mat roofs covering the junks and the mat roofs of the huts seem to merge together so that it’s impossible to see where the river ends and the riverbank begins.

And what a teeming population may be found there! Men, women, children, dogs, pigs and chickens, come and go, jumping from one boat to another, shouting, barking, growling, snorting and clucking with extraordinary enthusiasm.

Some cook their food in the open air. The installation is very primitive, but they cook all kinds of things in blackened pots – rice, fresh or smoked fish, iguanas –simmering either separately or together, and I assure you that this food is not always appetizing. In any case, there is nothing to praise or pleasant to smell.

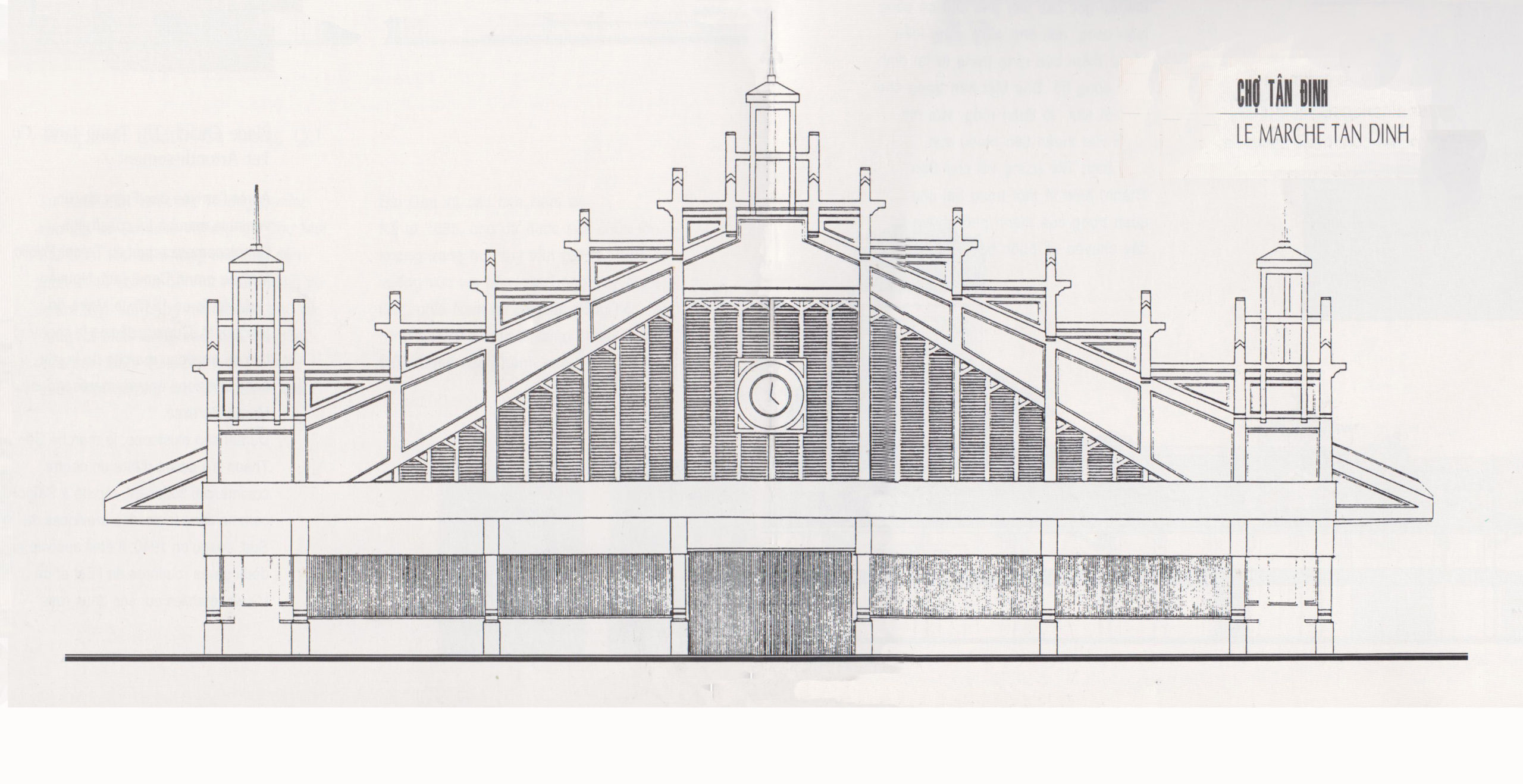

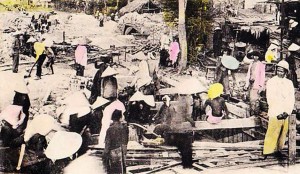

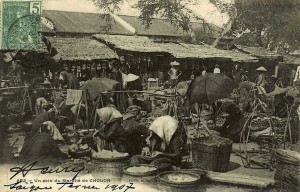

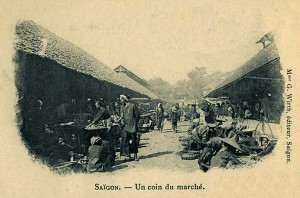

A corner of the old Chợ Lờn Market

In France, we certainly have on our canals, rivers, and navigable waterways, a large interesting population whose entire existence takes place on their houseboat, barge, barge, tug or other vessel; but that special world is very different from the world of these Annamite fishermen or conveyors, whose housing consists of a mat between the sleeper and the board of the boat and another mat between the sky and the sleeper. The charming cabins inhabited by our riverine populations – smiling habitations with nasturtium and morning glory framing their miniscule doors and windows – have nothing whatsoever in common with the tiny space which the poor Far Eastern boatman shares with a whole barnyard.

What I am saying is the result of an impression; because in fact, this misery hides a true opulence. Cholon city contains a population of 60,000 souls, this is where all the important transactions take place – rice from the fertile plains of the Delta, precious woods from the forest and other goods all flock here, thanks to the admirable network of canals, rivers and arroyos which spread in all directions.

This place is like Canton, a city of sizeable proportions, with banks, shops and boutiques, while the business monopoly belongs to the Chinese. They are well at home here, basking on their doorsteps with long pipes on their lips, in which they smoke tobacco mixed with opium; they go through the streets, their umbrellas under their arms and glasses on their noses – huge glasses with big round lenses that give the wearers the appearance of a toad.

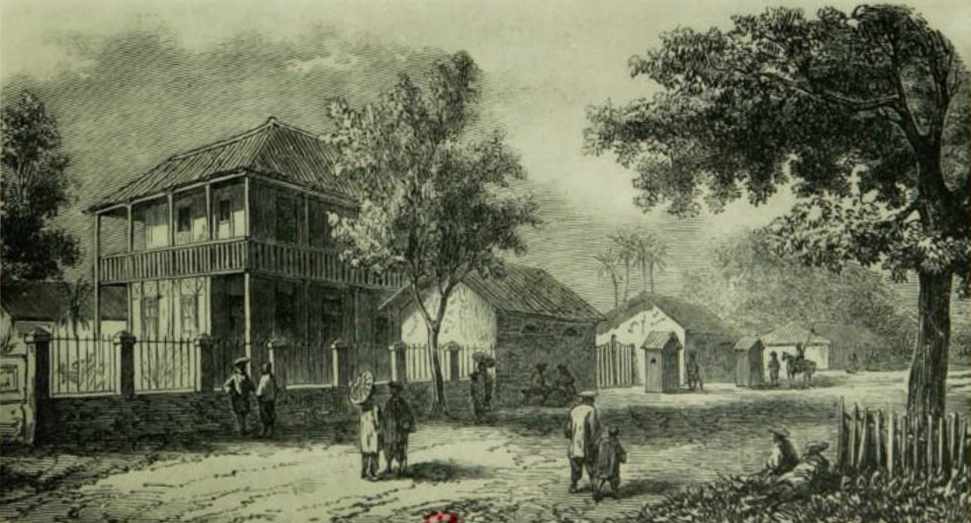

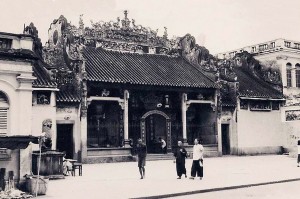

The Tuệ Thành (Suìchéng) or Guangzhou Assembly Hall

In front of each house is erected a small table which supports an urn surrounded by little candles, or rather scraps of wood garnished with red animal fat that are painted in various colors. These modest “candles” are destined to burn before the altars of the Buddha. I visit a pagoda where I see an earthenware horse and earthenware dogs, before which many of these candles burn: the ashes are carefully preserved, perhaps they are sold to the faithful?

In another Chinese temple, I take a small piece of wood shaped like an arrow on which are inscribed prayers. Quantities of these sticks are placed into a holder and the faithful shake them with all their might in front of the Buddha. The resulting noise brings wishes and prayers to the feet of the deity.

All this is in the same vein as the prayer wheels encountered at every moment on the waterways of the Middle Kingdom, or the strips of paper with printed invocations, which, when burned, send forth fragrant smoke to tickle the nostrils of the gods.

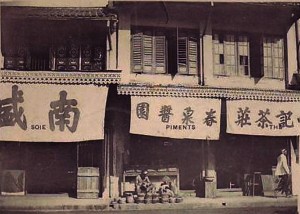

In front of the shops hang long vertical banners on which the merchant’s name and a description of the goods offered for sale is painted in Chinese characters, which are pretty much the most terrible headache that has ever been invented. We know, moreover, that it takes many years of study to learn to read and write the language of the Celestial empire.

Chinese shopfronts in Chợ Lớn

I enter another pagoda and I notice a Chinese book, which I flip through. This is an illustrated book with several engravings; in one of them, a woman is whipping a little boy who begs on his knees for mercy, hands clasped. Above this scene soars a fantastic bird, holding in its beak a pearl necklace, adorned with a ribbon. What can this mean? Probably some allusion to Chinese mythology. In any case, the drawing is rather crude.

After spending some time walking in the middle of this active population, I take the road back to the city.

En route back to Saigon, I see some buffalo driven by a child. These animals seem to hold Europeans in horror and it is very dangerous to approach them. Throughout the Indochina peninsula, the buffalo is for its inhabitants a valuable aid for field work or for transportation. In some districts, it is forbidden, under penalty of a fine, to kill them.

Of course, wild buffalo hunters are always free to pursue and kill these animals; but they are tough opponents, with whom it is dangerous to enter into conflict. Some local people hunt, it seems, with a special kind of weapon. Into their poor gun, over the powder charge – and God knows, the buffalo hunter does not economise on the powder! – they place a hard wood arrow with an iron tip. This projectile represents a considerable weight – up to 1,500gm – and can cause horrifying injuries. But it is necessary that there is a lot of game to shoot at, otherwise the result may be zero. The arrowhead is sometimes coated with curare, and in this case, any beast is sure to succumb, even if the injury sustained is light.

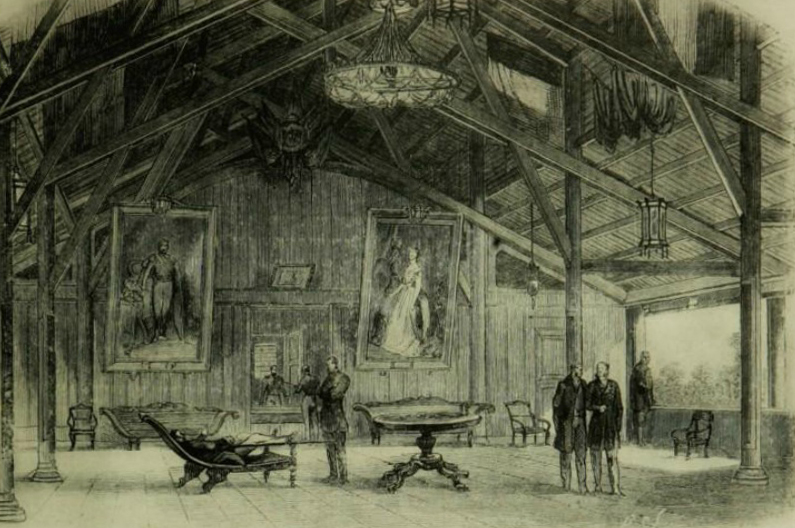

A scene at the old Bến Thành Market in Saigon

As wild buffalo generally move in herds, it is very dangerous to attack them, because if one is injured, its roar calls the herd around him and woe betide the hunter who lets himself be surprised! He would soon be gored by the terrible horns and crushed under the hooves of his furious opponents.

On my return to the hotel, I relax by taking a bath. The bathtub is made of stone and the installation does not lack comfort; in any case, it is much better, in all respects, to that in Pondicherry, where I still remember laughing at the half-full tub. The baths of the Hôtel de l’Univers are located in an annex across the street; there are showers and hydrotherapy facilities.

Once well rested, I leave for another trip into town. I visit a few bazaars stacked with the most disparate goods of European or Oriental provenance. But suddenly, the rain begins to fall; one of those heavy showers that falls in warm countries and which we are not used in our temperate climates.

Fortunately, the chance of my walk has brought me back in the environs of the hotel and a few quick strides permit me to find shelter; it was just in time!

I go back to my room and watch the rain fall. What bodies of water! It really looks like all the windows of heaven have opened. It is by seeing the deluge that I understand why the Chinese never go anywhere without their umbrella.

Chinese shops in Saigon

On the other side of the street may be found a tailor, a shoemaker and a Chinese laundry. These people work with a surprising relentlessness. The tailor has a sewing machine and it bites from morning until midnight without stopping. I am not surprised to hear that the small European worker, artisan or merchant can never compete against Chinese engaged in the same occupations.

We know that in a large city in the United States of America, it is the Chinese who have the monopoly of laundry. It is the same here.

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here

To read part 3 of this serialisation click here

To read part 4 of this serialisation click here

To read part 5 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.