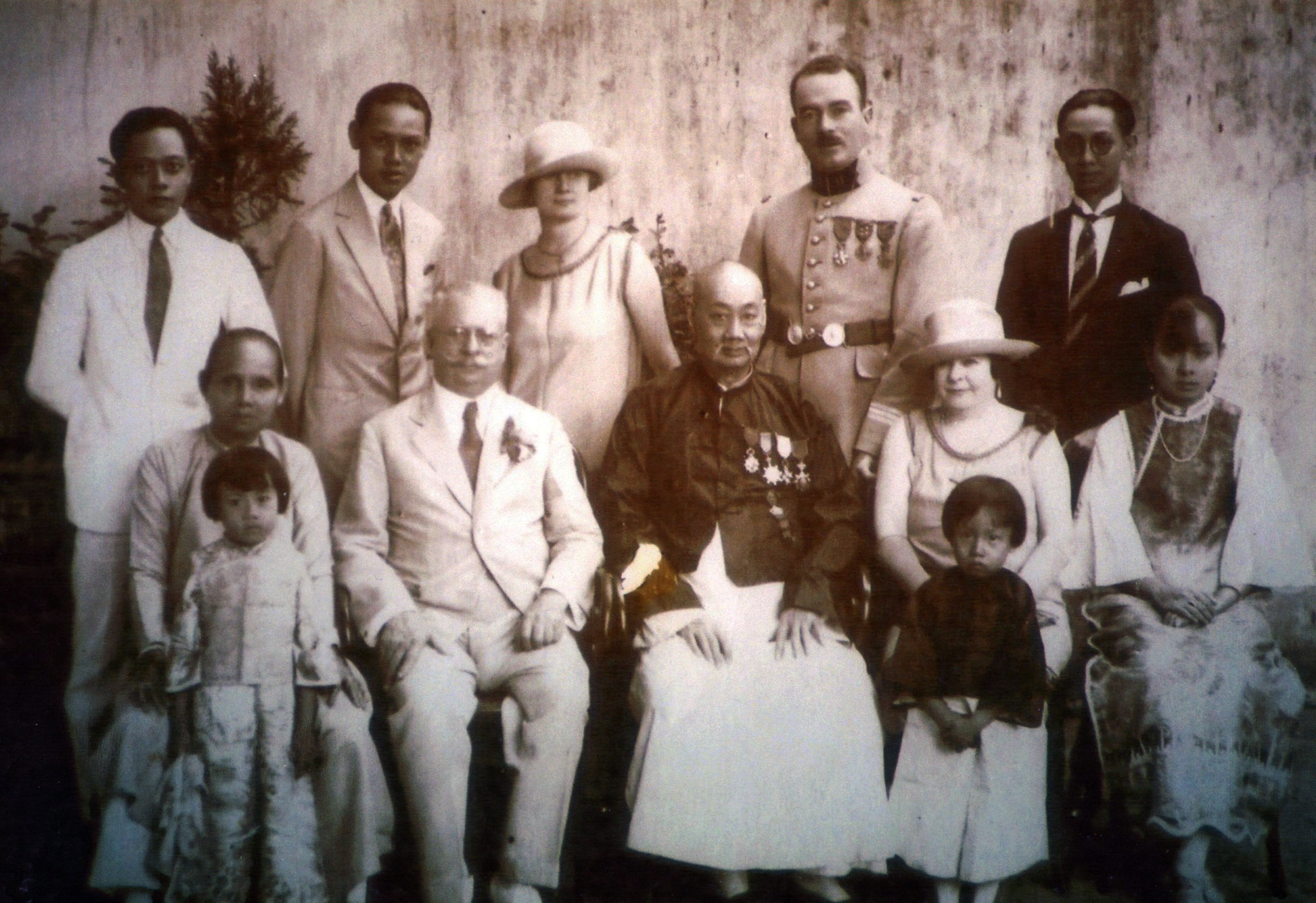

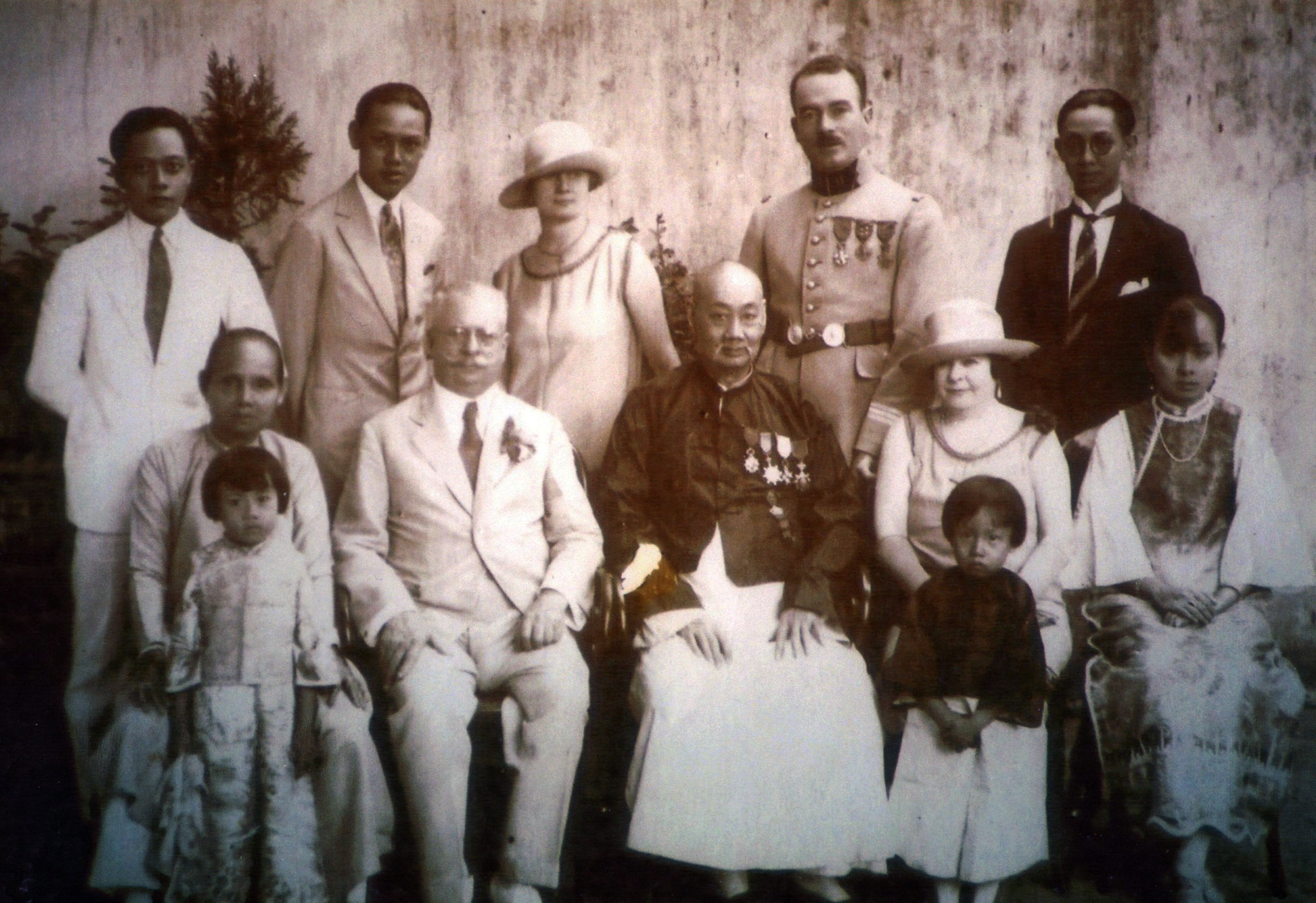

This rare family photograph of Quách Đàm, taken on the day he received a medal from the French government, was kindly provided by his great grandson, Mr Harrison W Lau.

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

Hải Thượng Lãn Ông boulevard (the former quai Gaudot) in central Chợ Lớn preserves several elegant old colonial shophouse buildings, but perhaps the most interesting of all is number 45, once the modest headquarters of Cantonese millionaire and philanthropist Quách Đàm.

Born in 1863 in Longkeng village, Chao’an district, Chaozhou prefecture of Guangdong province, Quách Đàm (郭琰 Guō Yǎn) left home in the mid 1880s to make his fortune in French Cochinchina.

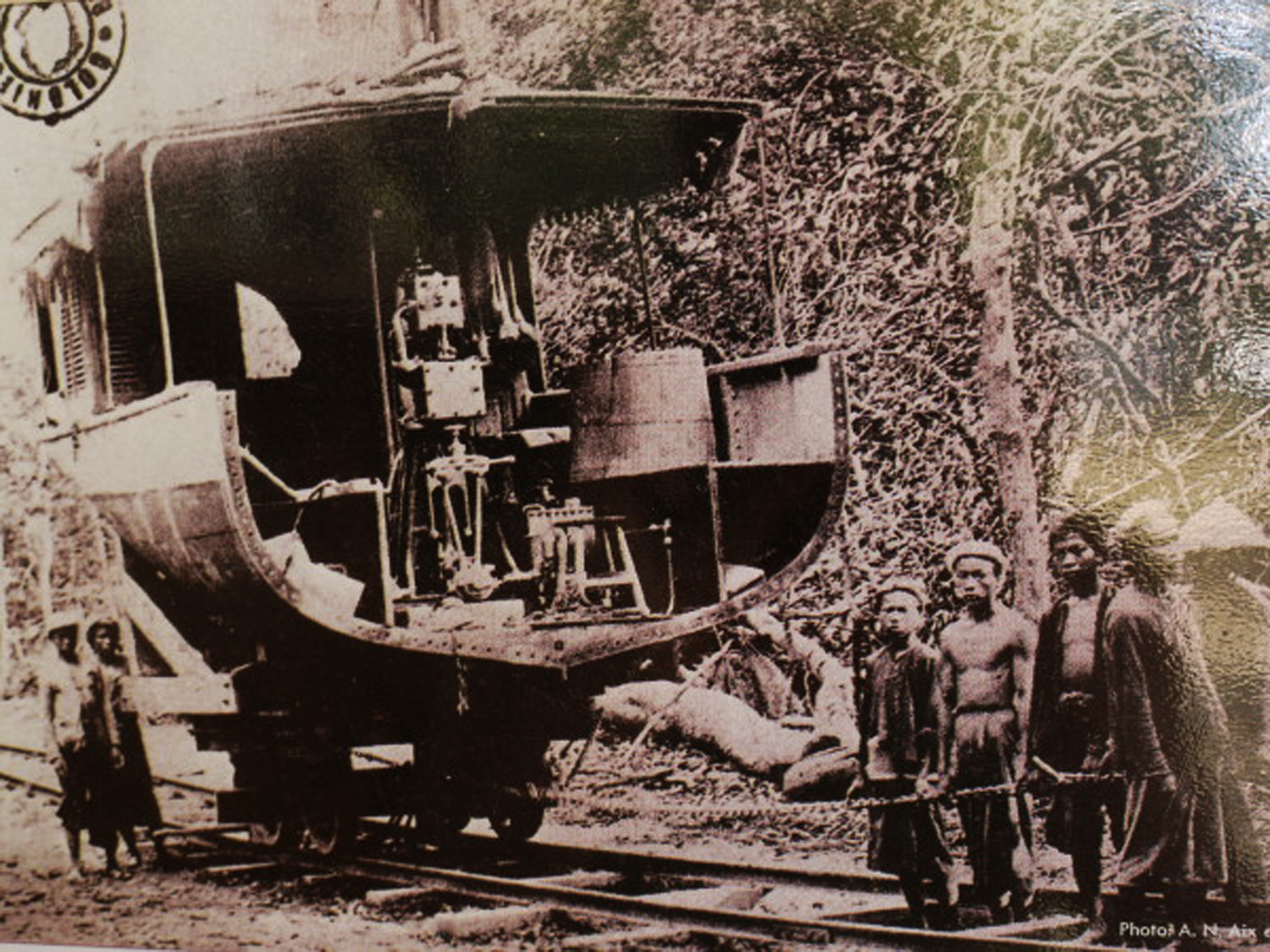

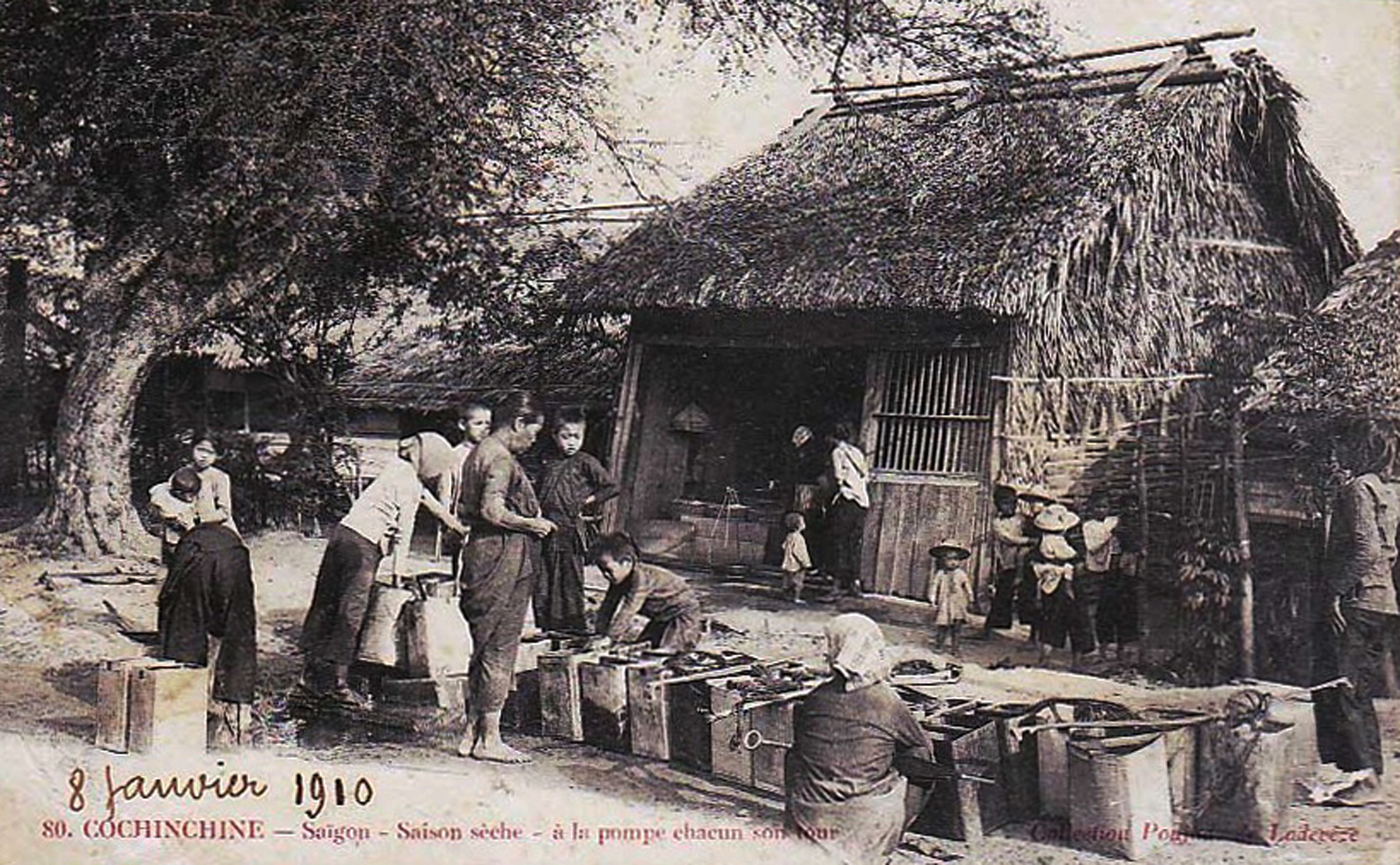

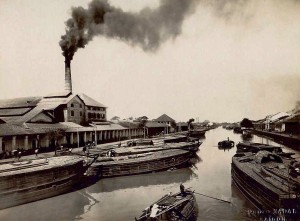

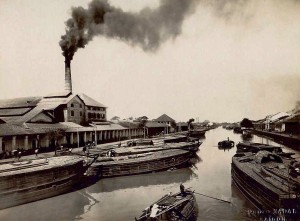

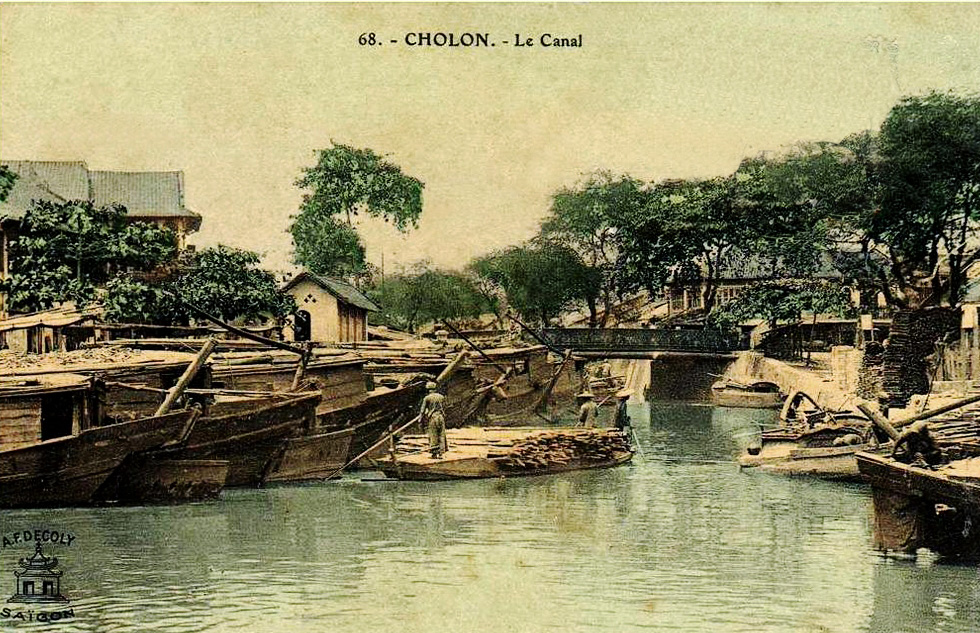

A paddy depot on the quayside

Starting out by buying and selling bottles, he later progressed to the trading of buffalo hides and fish bladders. By the 1890s, having ploughed the money he made from these early ventures back into business, he had acquired his own steamship and set himself up in Cần Thơ as a prosperous rice merchant.

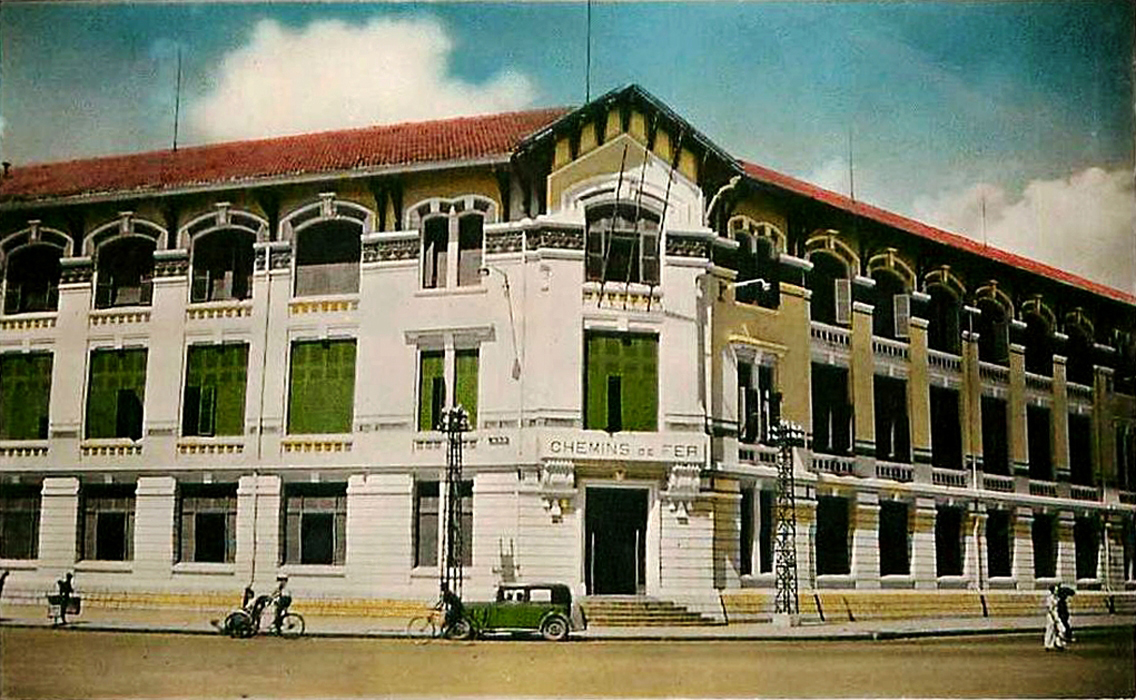

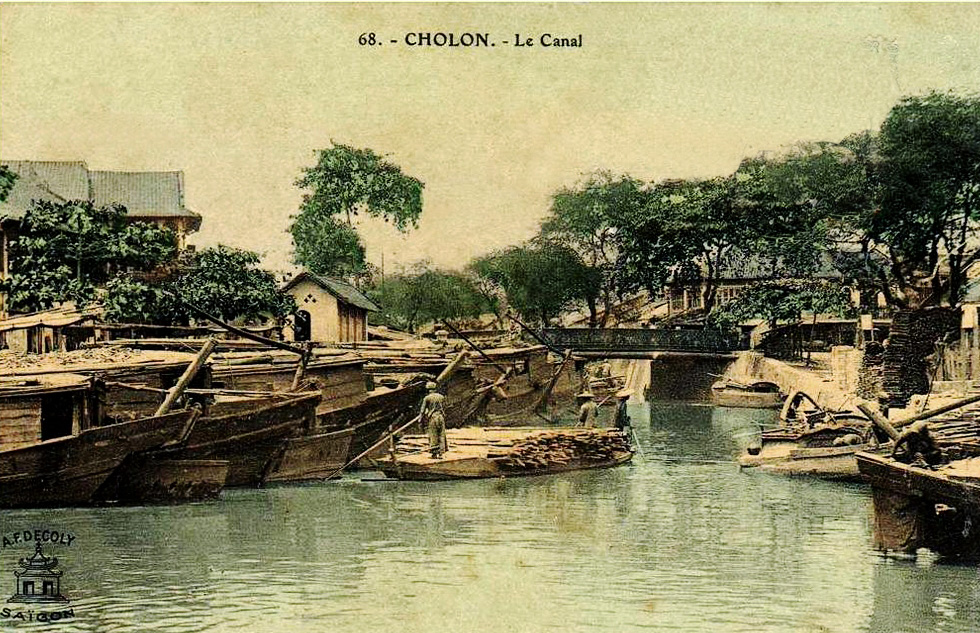

In around 1906-1907, Quách Đàm relocated to Chợ Lớn, founding a new company known as Thông Hiệp, its name a quốc ngữ romanisation of two auspicious characters from a Chinese poem. The company initially rented a magasin de dépôt at 55 quai Gaudot, a two-storey shophouse directly overlooking the Chợ Lớn creek which then ran right through the centre of the town.

However, a geomancer is said to have convinced Quách Đàm that the most auspicious shophouse on the wharf was in fact a few doors east at number 45, at a three-storey building which at that time housed the offices of soap makers Nam-Thai and Truong-Thanh. Beneath that building was said to be the head of a dragon whose body stretched out to sea, promising to whoever worked there that the money would keep flowing in.

The parapet of 45 Hải Thượng Lãn Ông (the former 45 quai Gaudot) still carries the “TH” (Thông Hiệp) logo

By 1910, Quách Đàm had relocated his headquarters to 45 quai Gaudot. However, despite his repeated attempts to purchase the building, the owner refused to sell. Quách Đàm was thus obliged to continue renting this modest shophouse as his company headquarters. Over a century later, it still bears the “TH” (Thông Hiệp) logo which Quách Đàm had inscribed on its parapet.

In subsequent years, in addition to his factory in Cần Thơ, Quách Đàm built two large rice husking mills at Chánh Hưng (now District 8) and Lò Gốm (now District 6). He also registered the Quach-Dam et Cie shipping company in Phnom Penh to manage his burgeoning fleet of four steamships. However, the business venture which really cemented his fortune was the acquisition in around 1915 of the Yi-Cheong Rice Factory, the largest and most profitable rice mill in Chợ Lớn.

By 1923, statistics published by the Revue de la Pacifique showed that every 24 hours, the amount of paddy processed in Quách Đàm’s mills amounted to 230 tonnes at Chánh Hưng, 250 tonnes at Lò Gốm and a massive 1,000 tonnes at Yi-Cheong, confirming his status as the most successful rice merchant in Cochinchina.

One of the numerous rice mills in colonial Chợ Lớn

With money came prestige and power. As early as 1908, Quách Đàm was one of the few Chinese businessmen to become a member of the Chợ Lớn Municipal Council, and in this capacity he served for many years as 3rd Deputy Mayor of Chợ Lớn, taking an active role in city affairs. He built a spacious family residence at 114 quai Gaudot, on the north bank of the creek, and is said to have enjoyed being chauffeured around town in what the French newspapers called his “beautiful automobile.”

It was during this period that Quách Đàm began to make a name for himself as a prominent philanthropist, “royally subsidising many hospitals, schools and workers’ associations and never remaining indifferent to poverty.” (obituary in the Echo Annamite, 1927). He was particularly active in funding local nurseries and schools for the blind. Quách Đàm’s great grandson Mr Harrison W Lau also reports that he was told by his grandmother Quách Điêu (Quách Đàm’s youngest daughter) that after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, Quách Đàm donated and shipped to Japan in his own boats around 4,000 tonnes of rice.

For much of the last decade of his life, despite being beset by ill health and also suffering partial paralysis, Quách Đàm continued to play an active role in Chợ Lớn’s business and community affairs. Today he remains best known for the crucial role he played in the establishment of the Bình Tây Market.

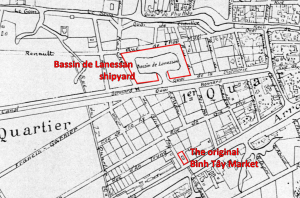

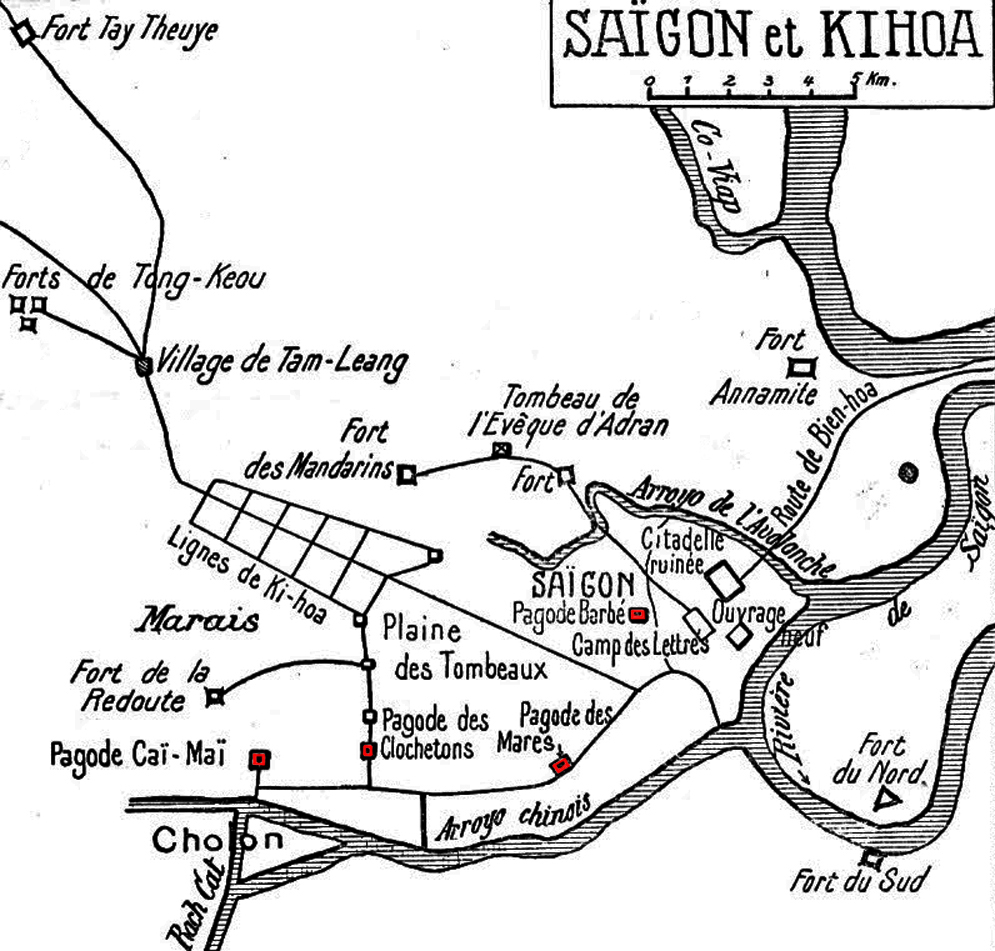

This 19th century map shows the Phố Xếp canal (marked in red) which connected the Chợ Lớn creek with the original Tai Ngon market (Chợ Sài Gòn)

Before the arrival of the French, the main market in the Chinese settlement went by the name of Dī Àn (堤岸) or Tai Ngon, literally meaning “embankment,” a name which is believed to reference the extensive reconstruction which followed the destruction of the Tây Sơn attack of 1782. In the 19th century, that market appears on several maps, not as Tai Ngon but as “Sài Gòn,” the name the French appropriated after 1859 to rechristen the former Bến Nghé as their new colonial capital, Saigon.

Located in the vicinity of the modern Chỗ Rẫy hospital, the old Tai Ngon market was originally connected to the Chợ Lớn creek by a waterway known as the Phố Xếp canal (now Châu Văn Liêm street).

After the conquest, the French established a new main market right in the centre of Chợ Lớn, on the site occupied today by the city post office, leading eventually to the abandonment of the old market and the gradual disappearance of the Phố Xếp canal.

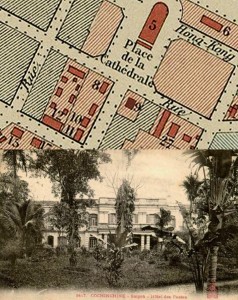

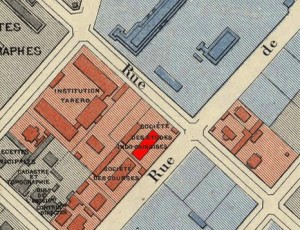

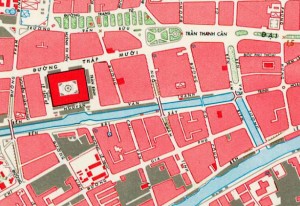

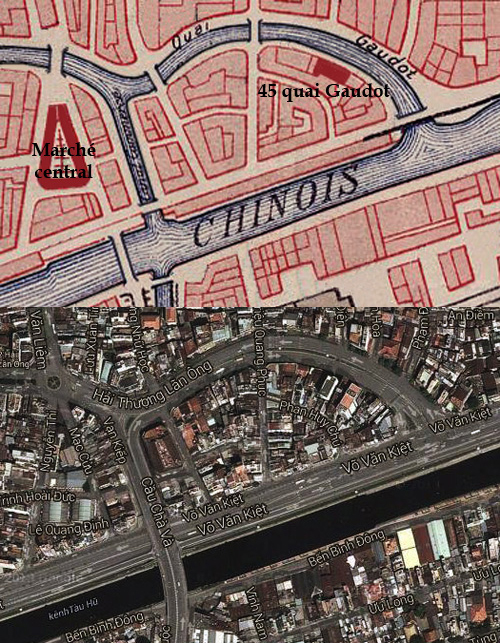

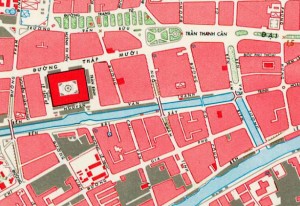

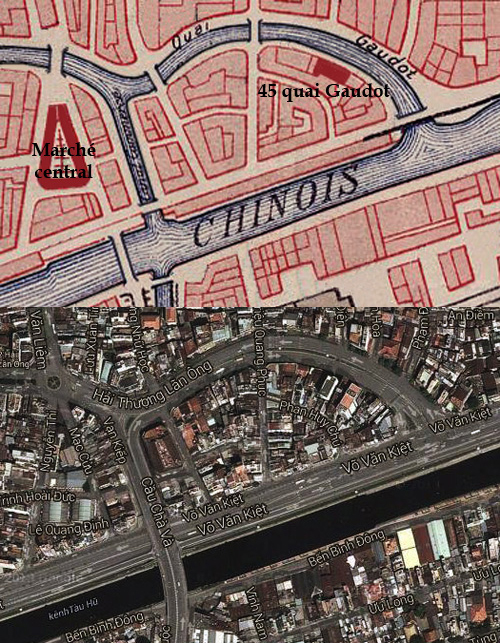

This 1923 map indicates the location of the Marché central de Cholon and Quách Đàm’s Thông Hiệp headquarters before the Chợ Lớn creek was filled

By the early 20th century, as Chợ Lớn grew in economic importance, French newspapers complained frequently that the Marché central de Cholon “had become too small for the ever-increasing number of its users.”

However, what really sealed the fate of the Marché central de Cholon was the 1923 scheme (completed in 1926) to fill the Chợ Lớn creek and its connecting waterways and replace them with roads. After that project was completed, merchants could no longer access the central market by boat.

In fact, for several decades before the filling of the Chợ Lớn creek, an ever-increasing number of merchants had preferred to do business at the original Bình Tây Market, which stood right next to the arroyo Chinois on the junction of quai de My-tho and rue de Binh-Tay (modern Võ Văn Kiệt-Bình Tây).

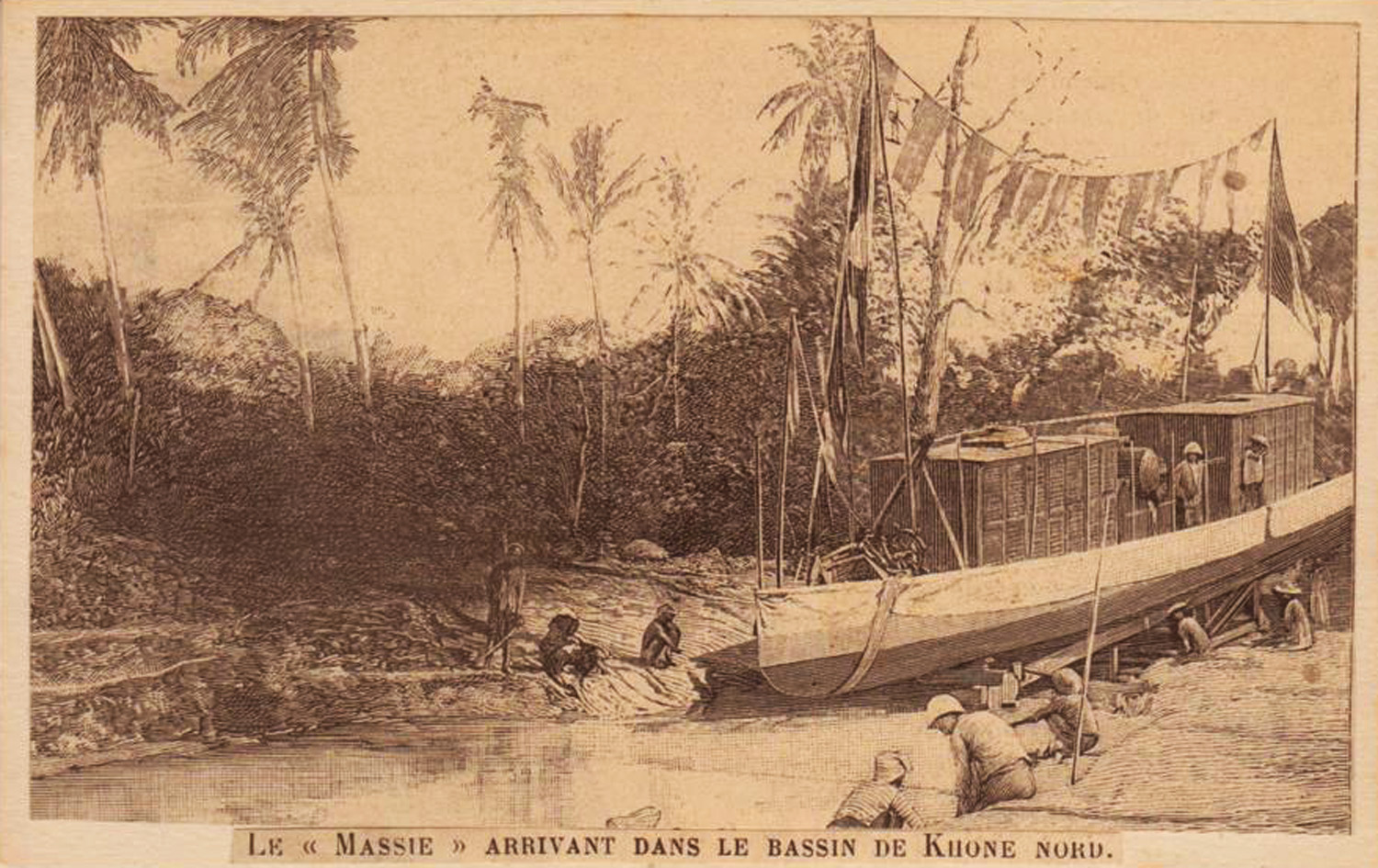

In 1893 a new waterway known as the Canal Bonard (originally named the Canal Fourès and known to the Vietnamese as the Bãi Sậy canal) was dug to connect central Chợ Lớn with the lower reaches of the Lò Gốm Creek. Located just a few blocks north of the arroyo Chinois and running parallel to it, this new waterway incorporated a large shipyard for the repair and construction of junks known as the Bassin de Lanessan.

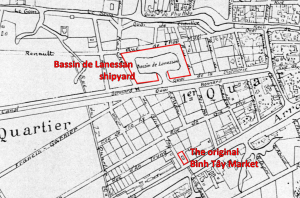

A 1907 map showing the locations of the original Bình Tây Market and of the Bassin de Lanessan shipyard on the Canal Bonard which was filled to build the second Bình Tây Market

In subsequent years, as the Canal Bonard became increasingly busy with merchant shipping, Quách Đàm bought large plots of land along its banks, including the Bassin de Lanessan shipyard. In 1923, seeing an opportunity to relocate the central market to a larger and more accessible location, he proposed to the colonial authorities the construction of a new and much larger Bình Tây Market on the 9,000 square metre shipyard site, to serve as the new central market of Chợ Lớn.

The Colonial Council gave its approval, the Bassin de Lanessan shipyard site was filled, and in 1925 Quách Đàm donated the land to the city and also contributed 58,000 Francs towards the construction costs of the new market.

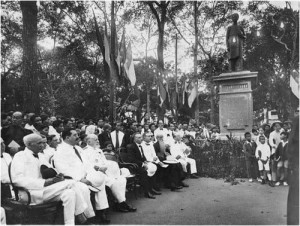

The new Bình Tây Market was Quách Đàm’s crowning achievement and garnered much praise and admiration in both local and colonial circles. Over the next two years, Quách Đàm, already a naturalised French citizen, received a succession of awards, including the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, the Chevalier de l’Étoilè Noire and the Chevalier de l’Ordre royal du Cambodge, as well as the Order of the Precious Brilliant Golden Grain (Order of Chia-Ho) from the Republic of China.

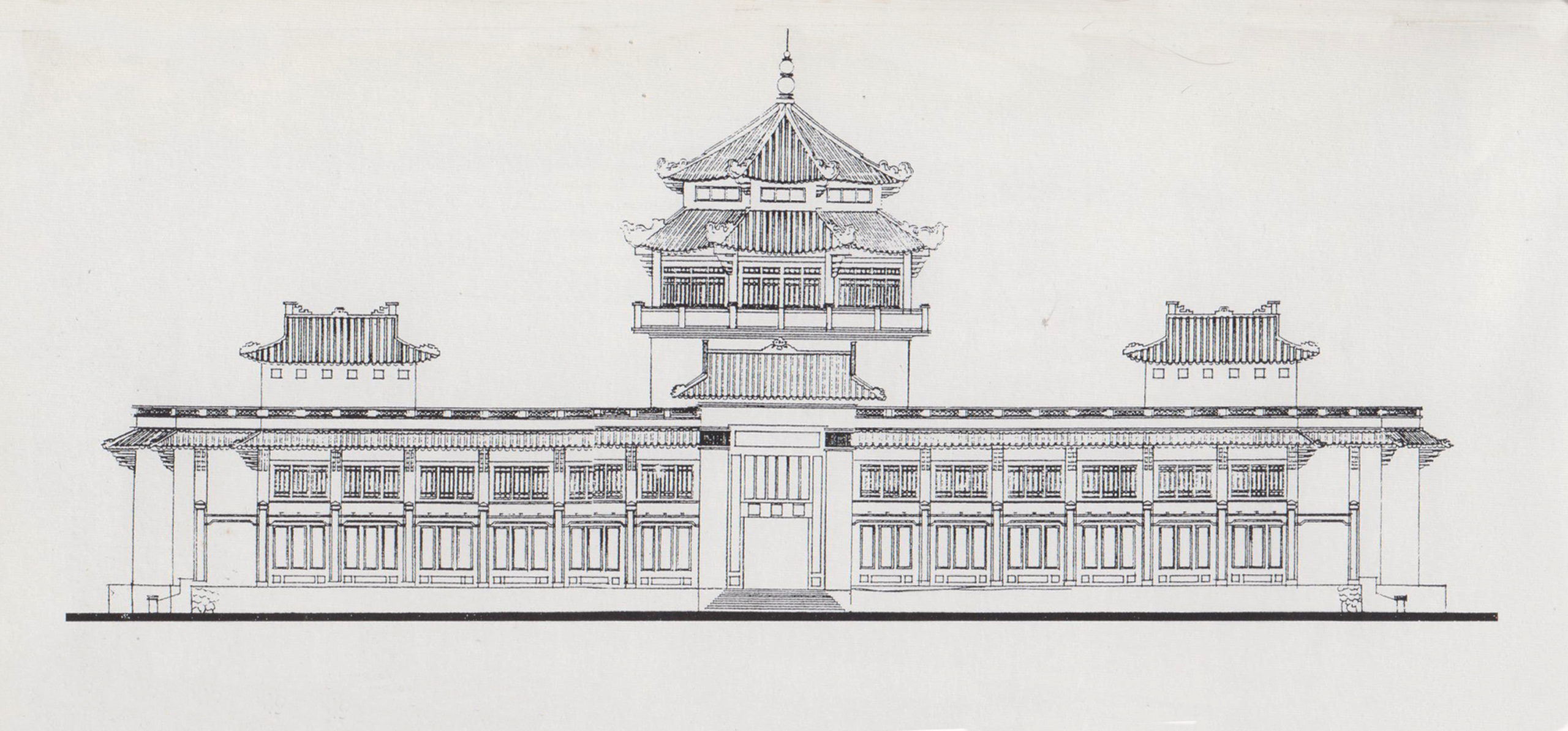

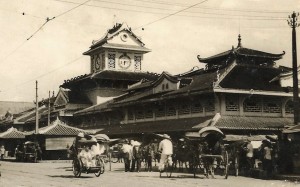

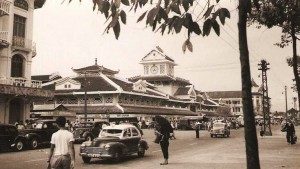

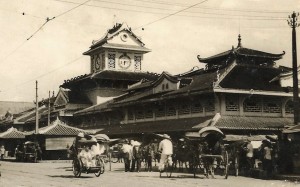

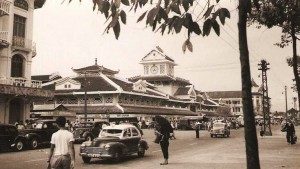

The new Bình Tây Market, pictured in the 1930s

Construction of the new Bình Tây Market began in February 1926 and was completed in September 1928. However, Quách Đàm never saw the finished market; he died on 14 May 1927, aged 65.

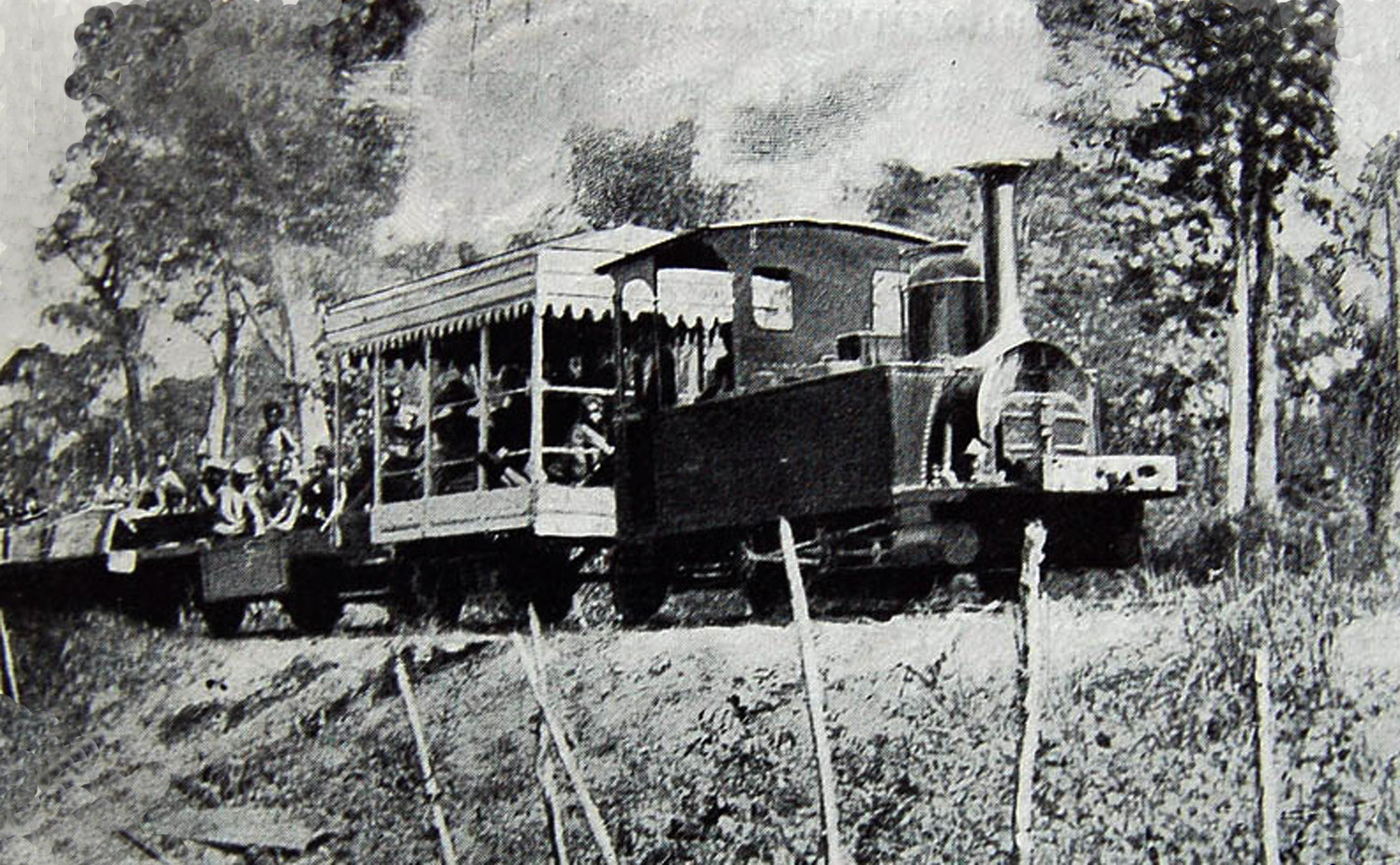

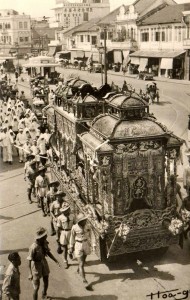

The Echo Annamite newspaper carried a long article describing Quách Đàm’s funeral on Sunday 29 May 1927. Special trams and trains were laid on to convey the great and the good to Chợ Lớn to join the funeral procession from 45 boulevard Gaudot to the family plot at Phú Thọ cemetery.

Those in attendance included: the Mayors of Chợ Lớn and Saigon and their senior staff; the heads of the Chinese congregations and the Chinese Chamber of Commerce; and the Directors of (amongst others) the Banque de l’Indochine, Banque Franco-Chinoise, Distilleries de Binh-Tay, Société Commerciale française d’Indochine, Maison Courtinat, Maison Denis-Frères, Usines de la Compagnie des Eaux et Electricité, the Services du Port, the Hôpital Drouhet, the Lycée Franco-Chinois and the Ecoles de filles de Cholon.

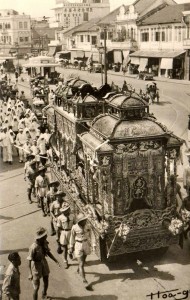

A Chinese funeral procession in Chợ Lớn

Two large huts had been built on the boulevard immediately outside the Thông Hiệp headquarters – one to accommodate the guests and the other to house the coffin and more than 1,500 commemorative banners and wreaths which had been sent from all parts of Cochinchina, Tonkin, Cambodia and even China.

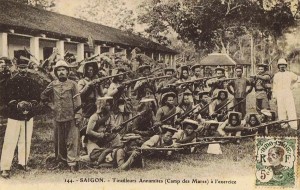

A camera crew from Indochine Films was on hand as the procession set off, led by family mourners, to the accompaniment of Chopin’s Funeral March performed by “several Annamite and Chinese orchestras.” Behind the hearse, family members held aloft a dais which displayed all of Quách Đàm’s honours on a large gold and blue silk cushion. They were followed by a guard of honour comprising riflemen from the Compagnie de Cholon du 1er Tirailleurs.

In order that as many people as possible could offer their respects, the procession did a complete circuit of the city, starting with eastern Chợ Lớn – rue Lareynière [Lương Nhữ Học], rue des Marins [Trần Hưng Đạo B], rue Jaccaréo [Tản Đà], quai Mytho [Võ Văn Kiệt] and back to boulevard Gaudot [Hải Thượng Lãn Ông] – and then returning to quai Mytho and heading along the Arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé creek] into the west of the city. There it turned up rue de Paris [Phùng Hưng] and made its way north along rue Boulevard Tong-Doc-Phuong [Châu Văn Liêm] and rue Thuan-Kieu [Thuận Kiều] towards the cemetery at Phú Thọ. “As they processed,” added the Echo Annamite reporter reverently, “the banners shimmered and the usually noisy city descended into respectful silence.”

This 1966 map shows the Bình Tây Market at a time when deliveries were still made by boat

Fourteen months later, the Annales coloniales reported that on 28 September 1928 the new market was inaugurated in the presence of the Governor of Cochinchina, amidst a host of festivities which included a cavalcade and a fireworks display.

After Quách Đàm’s death, his eldest son Quách Khôi took over as director of the Thông Hiêp company, but in May 1929 tragedy struck when Quách Khôi himself died suddenly and Chợ Lớn was treated to another grand public funeral.

Later that year, with the authorisation of Chợ Lớn Municipality, Quách Đàm’s family commissioned an elaborate marble fountain in the central courtyard of the Bình Tây Market, surrounded by bronze lions and dragons and topped with a bronze statue of Quách Đàm by Paul Ducuing (1867-1949), the French sculptor who in 1925 had created the gilded bronze statue of Emperor Khải Định seated on his throne in the Ứng Lăng Mausoleum of Emperor Khải Định in Huế.

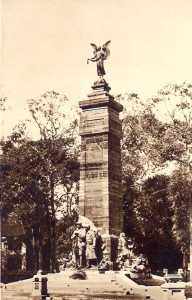

Ducuing’s statue of Quách Đàm on the plinth at Bình Tây Market before 1975

Inaugurated on 14 March 1930, it depicts the man French newspapers dubbed the “king of commerce,” holding in his left hand the act by which he had donated to the city of Chợ Lớn the land on which the market was built. In his right hand is a scroll which lists the philanthropic works for which he was known – Écoles, marchés, oeuvres, assistance (“Schools, markets, works, assistance”). The opening ceremony for the fountain “was presided over by M. Eutrope representing the Governor of Cochinchina (absent from Saigon), M Renault, resident-mayor of Cholon and a large audience of European, Annamite and Chinese personalities.” A friend of the family delivered “a remarkable speech recalling the beautiful life of the deceased.”

After 1975, the Ducuing statue was removed from its plinth and placed in store. However, in 1992 it was returned to public view in the rear courtyard of the Hồ Chí Minh City Fine Arts Museum, where it can still be seen to this day.

In recent years, a bust of Quách Đàm has been installed in front of the statueless plinth. Behind it, the Chinese inscription of 1930 reads: Mr Guō Yǎn was from Longkeng, Chao’an, Chaozhou, Guangdong province and came to Việt Nam when he was young to build a family while working in the rice business; he became very wealthy and generous, and as a good and righteous person, he resolved to build a new market for Dī Àn [Chợ Lớn]. Through great effort, he finally realised this and the government awarded him with this bronze statue to remember him. Guō Yǎn was born in 1863 and died in 1927 (translation by Damian Harper).

Bình Tây Market pictured in the 1950s

Following the death of Quách Khôi, his younger brother Quách Tiên took over the reins of power at Thông Hiệp, but according to historian Vương Hồng Sển, his willingness to act as guarantor for the debts of insolvent traders during the years of economic crisis eventually dragged Thông Hiệp into debt.

After 1933, the Thông Hiệp company name disappears from the records, though in 1937 and 1939, Quách Tiên reappears as proprietor of the “Plantation Quach-Dam,” a rubber plantation in Biên Hoà province – with its registered office still at 45 boulevard Gaudot in Chợ Lớn.

Another rare photograph of Quách Đàm and his wife from the family collection of his great grandson, Mr Harrison W Lau

45 Hải Thượng Lãn Ông (the former 45 quai Gaudot) in Chợ Lớn was once Quách Đàm’s Thông Hiệp company headquarters

Before 1925 a creek ran through the centre of Chợ Lớn – today the roundabout in front of the Chợ Lớn post office has replaced the bridge

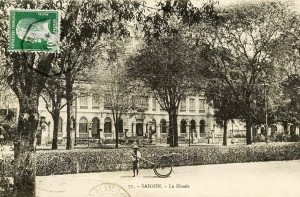

Filling of the Chợ Lớn creek was still in progress when this photograph of the Marché central de Cholon was taken in 1925

Then and now: central Chợ Lớn in 1923 before the creeks and canals were filled and the current Google Maps view of the same location

The original Bình Tây Market, which stood right next to the arroyo Chinois on the junction of quai de My-tho and rue de Binh-Tay (modern Võ Văn Kiệt-Bình Tây).

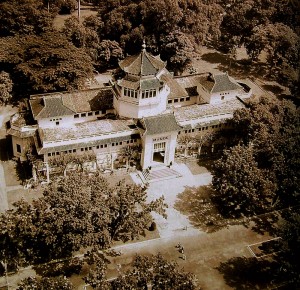

An aerial shot of the Bình Tây Market taken in the early 1950s

The rear yard of the Bình Tây Market was originally a wharf on the canal Bonard (known to the Vietnamese as the Bãi Sậy canal)

The Paul Ducuing statue of Quách Đàm is now kept in the rear courtyard of the Hồ Chí Minh City Fine Arts Museum

The bust of Quách Đàm, located in front of the fountain at Chợ Lớn’s Bình Tây Market

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.