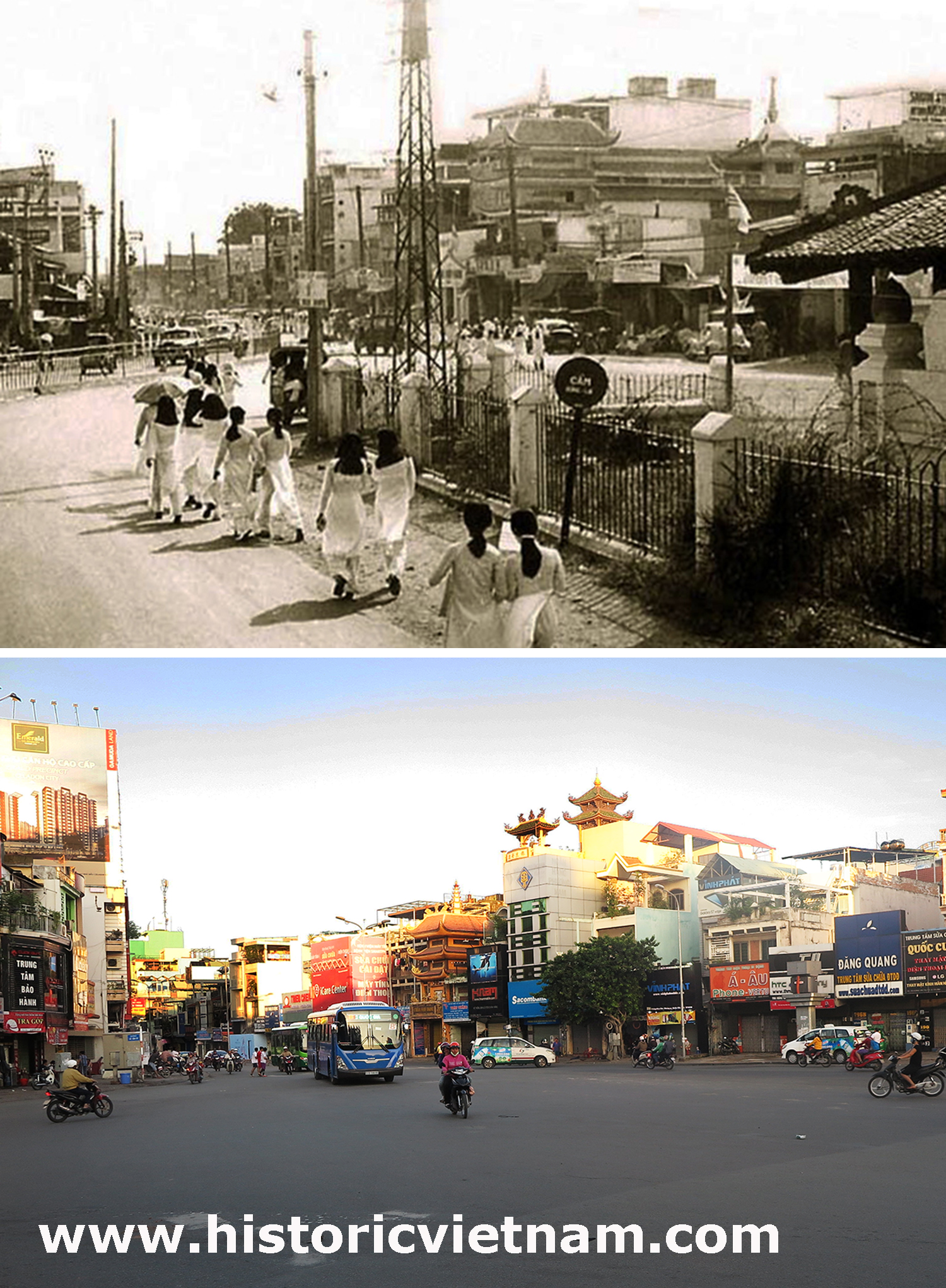

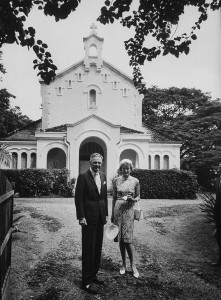

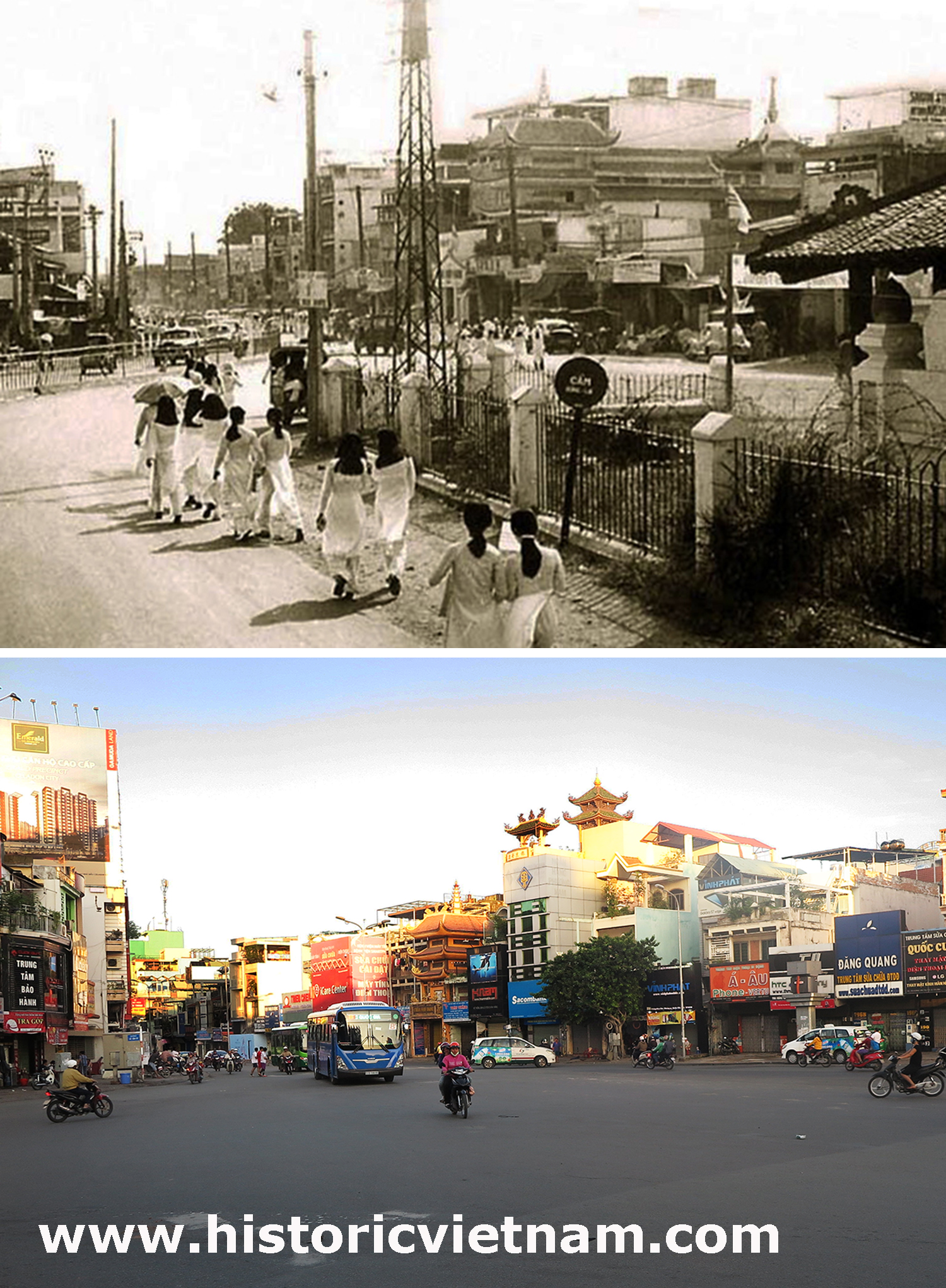

Saigon – A 1960s shot of the Bishop Pigneau de Behaine Mausoleum (photographer unknown), which was bulldozed by the city authorities in 1983 to make way for the Lăng Cha Cả intersection, and the same view today (14 August 2017)

If you’re just off the plane and heading west into the city, it’s hard to avoid the busy six-way Lăng Cha Cả intersection south of Hồ Chí Minh City’s Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport. But it’s even harder to believe that this was once the site of a national monument – the grand mausoleum of Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine.

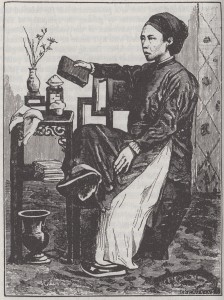

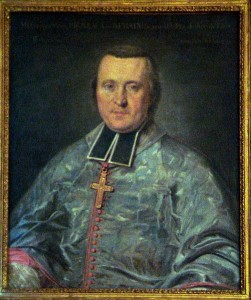

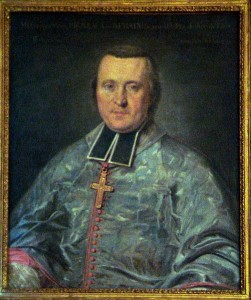

Pigneau de Béhaine, painted by Maupérin during his 1787 trip to Paris with Crown Prince Cảnh, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society

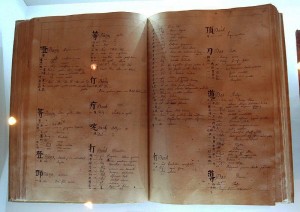

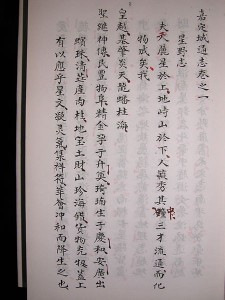

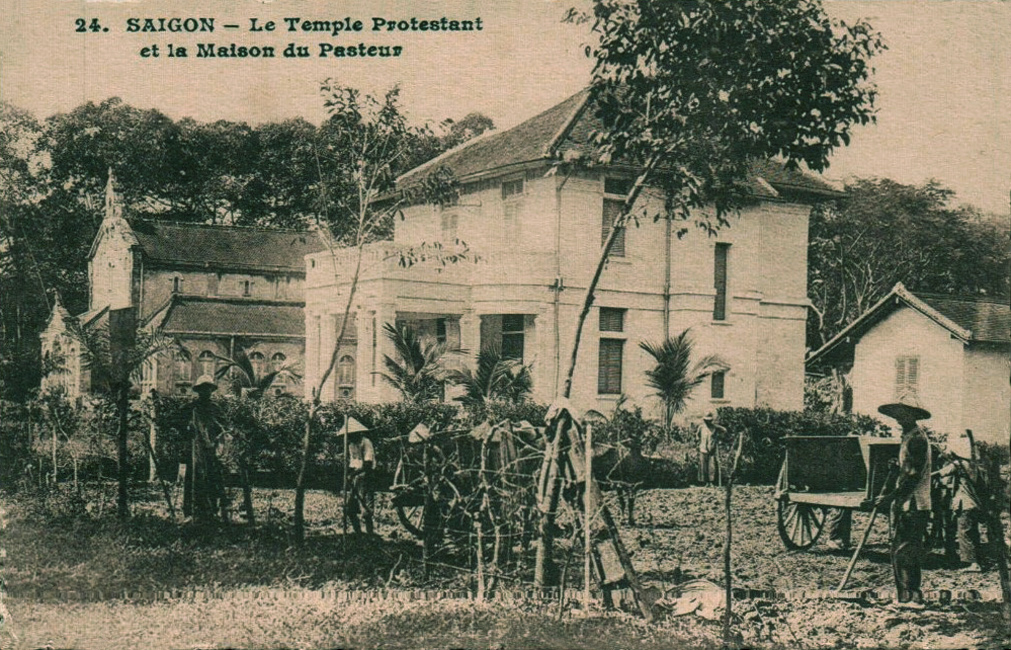

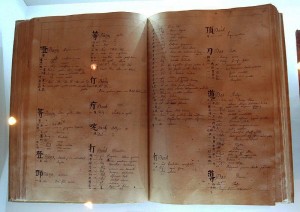

Monsignor Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau de Béhaine (1741-1799) first came to Việt Nam as a missionary with the Paris Foreign Missions Society in the late 1760s. In around 1775 he set up a seminary on the island of Phú Quốc, off the coast of Hà Tiên in the Mekong Delta. It was there that he mastered both Chinese and Vietnamese and worked with Vietnamese colleagues to compile the Dictionarium Anamitico-Latinum (Vietnamese-Latin dictionary, 1772) before his elevation to the post of Bishop of Adran and Apostolic Vicar of Cochinchina in 1774.

In 1777, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later King Gia Long) arrived on the island and sought protection at Pigneau’s seminary. The sole survivor of the Đàng Trong (Huế) royal family which had been massacred by the Tây Sơn, he was offered shelter by Pigneau and the two men quickly became close friends.

Pigneau subsequently pledged his support for the Nguyễn cause and over the next 15 years he became Ánh’s close confidant and indefatigable champion in the war against the Tây Sơn, procuring munitions and other military supplies for his armed forces.

Seven-year-old Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, painted by Maupérin during the prince’s 1787 trip to Paris with Pigneau, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society

In February 1787, Pigneau left for France, taking with him Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s young son and heir, Prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh. By the terms of the subsequent Treaty of Versailles, signed on 21 November 1787, the court of Louis XVI promised military support for Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in exchange for economic and territorial concessions in Việt Nam. However, due to the subsequent political situation in France, the Treaty was never implemented and Pigneau was obliged instead to use funds he had raised in France to recruit a force of mercenaries.

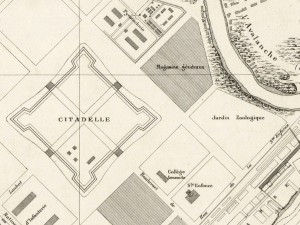

By the time Pigneau arrived back in Việt Nam in 1789, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh had retaken his old base at Gia Định. The team of French officers Pigneau had enlisted brought with them state-of-the-art weaponry and helped to train Ánh’s troops in modern infantry tactics and the use of heavy artillery. A naval workshop was set up in Bến Nghé (Saigon) to assemble a fleet of modern warships and a series of major fortifications was built, including the massive 1790 Gia Định Citadel, which became the temporary Nguyễn royal capital. In the 1790s, these military reforms enabled Ánh to launch a series of successful campaigns against Tây Sơn bases in the south-central region, paving the way for his final victory in 1801.

Pigneau’s 1772 Dictionarium Anamitico-Latinum, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

During the 1790s, as Nguyễn Phúc Ánh took the fight back to the Tây Sơn, Pigneau de Béhaine served as adviser at his court in Gia Định and tutor to his son Prince Cảnh.

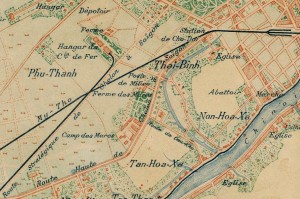

Writing in the 1880s, Pétrus Ký gave a fascinating account of the life and death of Pigneau de Béhaine: “Following his return from France, the bishop of Adran lived in Saigon, in a house called the Dinh Tân Xá which Nguyễn Phúc Ánh had built for him at the outer corner of the citadel, at the spot where the gunpowder magazine is now situated [now the site of the Hồ Chí Minh City History Museum]. The Christians of Thị Nghè also had their church close by, on the edge of the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek], in the parish of Tân Sơn, now the location of the bishop’s tomb.”

During this period, in addition to tutoring the young Crown Prince Cảnh, Pigneau also accompanied him on several military campaigns against the Tây Sơn, including the defence of Diên Khánh in 1794.

The main gate of Diên Khánh citadel in Khánh Hòa Province where Pigneau died

And it was on one of these campaigns, the seige of Quy Nhơn of 1799, that “after thirty-three years of a very rough and laborious life,” the bishop succumbed to acute dysentery.

“Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, driven by a genuine affection for the prelate who had rendered to him such eminent services, sent his best doctors and employed every possible means to conserve his life. Prince Cảnh came every day to visit his master, and Ánh himself came several times to see his benefactor, despite his concerns about the ongoing siege of Quy Nhơn, from which he tore himself away out of a sense of gratitude.”

Pierre Pigneau de Béhaine died on 9 October 1799, “in the arms of M Lelabousse, a missionary who had accompanied him.” Having received the sad news, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh sent “a beautiful coffin, together with silk for wrapping the body.”

In 1925, one scholar cited an inscription at the Lăng Ngọc Hội, 8km from Nha Trang, which suggested that Pigneau was actually laid to rest there rather than in Gia Định. However, other French sources make no mention of this. According to Pétrus Ký, on 10 October 1799, Crown Prince Cảnh accompanied the corpse as it was placed on one of the Nguyễn ships and returned to Gia Định for burial.

The interior of Pigneau’s Dinh Tân Xá in the grounds of the Archbishop’s Palace at 180 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu

Arriving in Gia Định on 16 October, Pigneau’s body was placed in the Dinh Tân Xá, where it lay in state for a month. Crown Prince Cảnh “considered himself as a disciple and eldest son of his master the prelate, for whom he was in deep mourning.” Cảnh had a special temporary palace built opposite the bishop’s house and stayed there day and night, receiving many mandarins who came from all parts of the kingdom “to render illustrious funeral honours to the deceased.”

A French architect named Barthélemy was commissioned to build a Nguyễn dynasty style mausoleum in Tân Sơn village, while Crown Prince Cảnh was entrusted with the detailed arrangements for the funeral ceremony. Despite the ongoing campaign in Quy Nhơn, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh himself made time to sail south to Gia Định to attend Pigneau’s funeral on 16 December 1799.

Pétrus Ký describes how the procession from the Dinh Tân Xá to the newly-built mausoleum set off at around 2am on 16 December 1799, led by Prince Cảnh.

The decorative screen in front of the Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum

“A large cross, formed from artfully-arranged lanterns, was carried at the head of the procession, followed by a series of elaborately carved red and gold portable shrines, each held aloft on an ornate dais and carried by four men.” The first housed a stele bearing the characters 皇天主宰 (Huáng tiān zhǔ zǎi or Hoàng thiên chúa tể, meaning “Sovereign Lord of Heaven”) in gold lettering. The second contained an image of St Paul and the third an image of St Peter, patron of the bishop of Adran. The fourth contained an image of the guardian angel and the fifth an image of the Blessed Virgin.

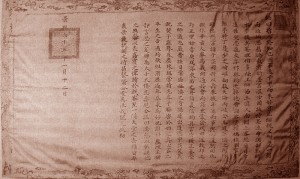

Then came a great standard measuring some 15 feet in length and made from damask, on which were embroidered in gold letters the titles conferred on the bishop of Adran by the King of France and the Lord of Đàng Trong [Nguyễn Phúc Ánh], as well as those of his episcopal office.

After this came a litter housing the insignia of the prelate, his cross and his mitre, which was carried directly in front of the hearse.

Another colonial-era image of the Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum

On either side of these shrines and litters walked “a large number of Christian young people and clergy from every church in Cochinchina.”

The hearse carrying the body of the bishop was “a beautiful litter of about 20 feet in length, carried by 80 picked men, and covered by an embroidered gold canopy.” On it was placed “the magnificent coffin….. covered with beautiful damask, set in a frame and surrounded by 25 large lit candles.”

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s royal guard, comprising more than 12,000 men, was arranged in two lines, with field guns at the head of each line. “One hundred and twenty war elephants with their escorts and mahouts walked on both sides. Drums, trumpets and both Annamite and Cambodian military music accompanied the mournful march, which was lit by a prodigious number of candles and torches and more than 2,000 lanterns of different shapes. At least 40,000 men, both Christians and pagans, followed the convoy.”

An image of the mausoleum from Charles Lemire’s 1884 book L’Indo-Chine, Cochinchine française, royaume de Cambodge, royaume d’Annam et Tonkin

Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh was present, along with his mother, his sister, his queen, his children, all the ladies of the court and the mandarins of different government departments. “All wanted to express their regret at the eminent and distinguished prelate who was no more, following his remains to the grave which had been prepared to receive him.”

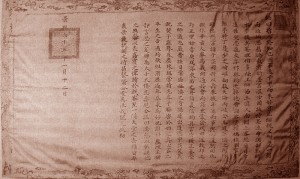

Arriving at the grave, a missionary named Father Liot performed the ceremonies of the Catholic liturgy. Once the Christian burial ceremony was finished, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh stepped forward and gave a tearful funeral elegy which he is said to have composed himself. This elegy had been transcribed onto embroidered silk and was “presented to the late bishop in the form of a posthumous diploma.”

Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s elegy recounted Pigneau’s efforts to obtain official French military assistance from Louis XVI and explained how, despite being “met with adverse conditions midway through his endeavours,” he had gone on to “marvelously save the situation with his extraordinary plans.”

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s funeral elegy was transcribed onto embroidered silk

It described Pigneau as “a precious friend, whose character fitted so well with mine… the intimate confidant of my most secret thoughts… who came to my kingdom and never left me, even when fortune eluded me”… “We were such friends and so familiar together that when my business called me out of my palace, our two horses walked abreast. We never had anything but the same heart.”

“After the funeral oration, the clergy and the Christians withdrew, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, alone with his mandarins, offered the sacrifices they were accustomed to make for souls of the deceased. Then Prince Cảnh and royal ministers each read out their own eulogies.”

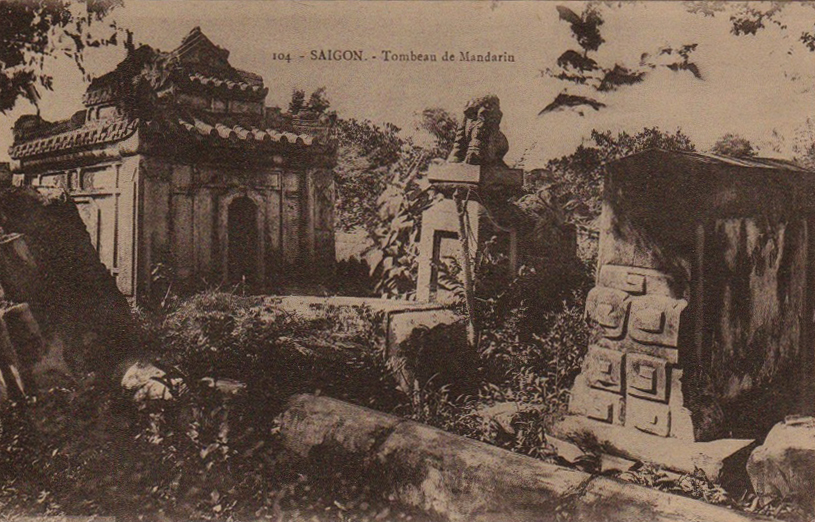

Writing in 1884, Charles Lemire also mentioned the “curious details” of Pigneau’s funeral as recounted by an eye witness named Father Bouillevaux, who gives us a detailed description of the mausoleum constructed over the tomb.

A 1960s photograph of the mausoleum shrine with its embossed coat of arms of the bishop

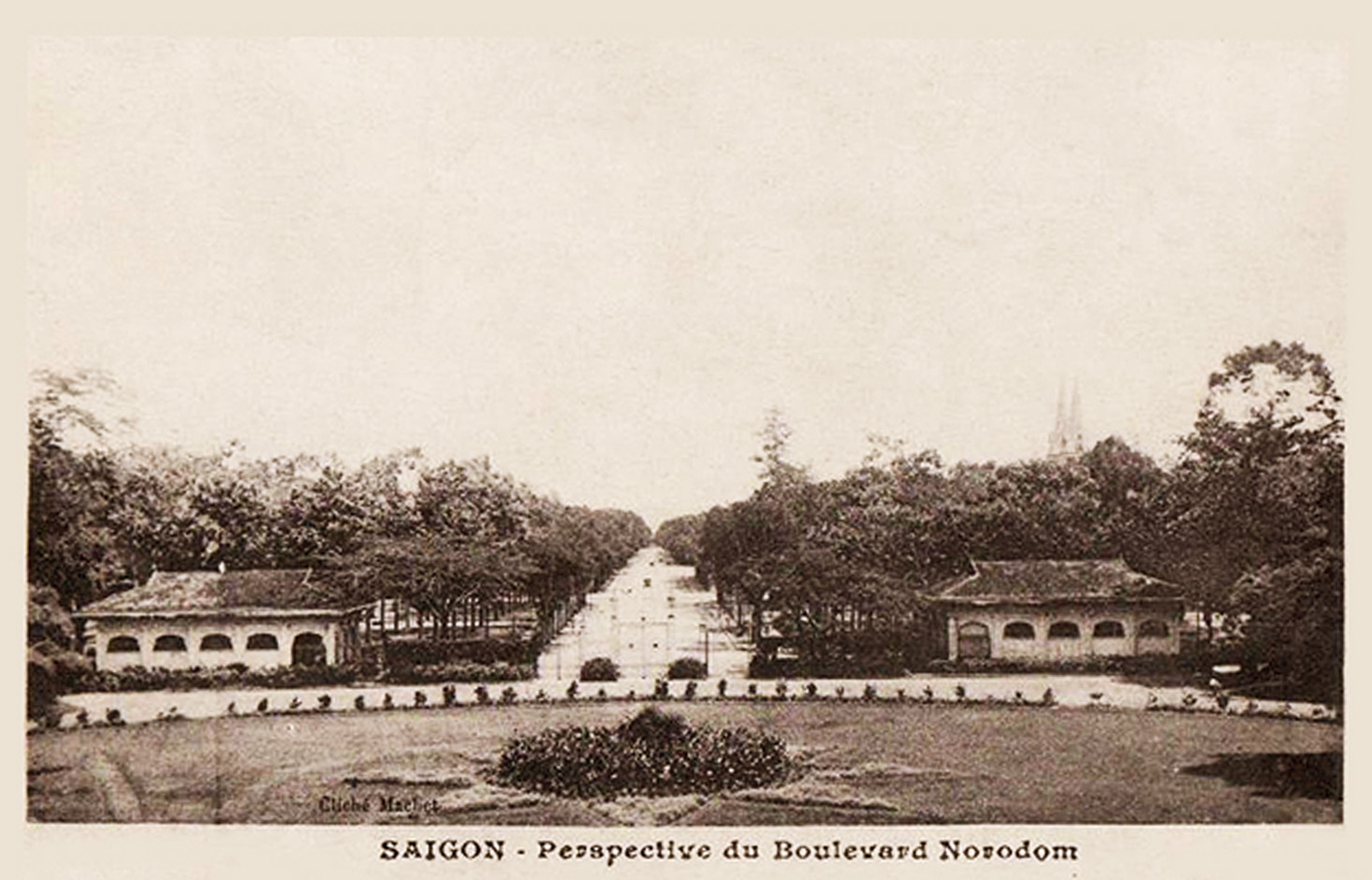

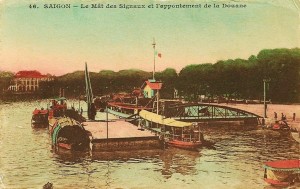

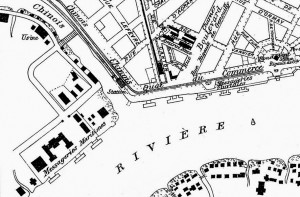

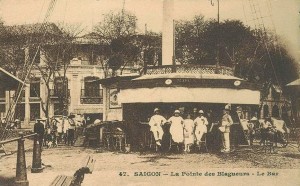

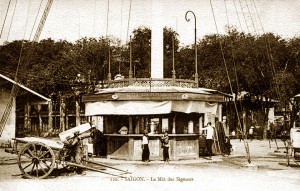

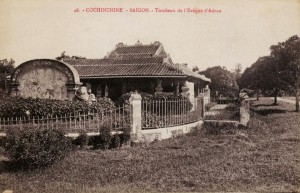

Known locally as Lăng Cha Cả, the mausoleum in which Pigneau de Béhaine was buried was located in a large rural clearing near Tân Sơn village. Designed in the Nguyễn dynasty style, it was supported by a frame of precious wood and topped by a traditional yin-yang tiled roof. In front of the building stood a large screen (bình phong).

Inside the mausoleum, behind a kowtowing hall (bái đường), was the tomb of Pigneau de Béhaine, positioned in the centre of the building and featuring a stele inscribed with Chinese characters describing the prelate’s life and work. At the rear of the building was a shrine decorated with “the embossed double coat of arms of the bishop, on whom King Louis XVI had conferred the title of count.”

At the time of the funeral, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh ordered “a guard of honour of 50 men to be posted outside the mausoleum in perpetuity.” While that order may not have been carried out for long, it is said that the mausoleum remained an important place of pilgrimage throughout the pre-colonial era.

The Pigneau de Béhaine statue which stood in front of the Notre Dame Cathedral from 1902 to 1945

After the arrival of the French, Pigneau continued to be honoured as a great statesman, thanks to the pivotal role he had played in Franco-Vietnamese relations and the fact that the terms of the abortive Treaty of Versailles had been used in the 1850s as a basis for French claims on Vietnamese territory.

As early as 1861, Admiral-Governor Léonard Charner declared the Lăng Cha Cả a national heritage site and in 1902 a statue of Pigneau de Béhaine was installed in front of the Notre Dame Cathedral. The statue depicted Pigneau holding in his right hand the 1787 Treaty of Versailles and with the other hand guiding his student, Crown Prince Cảnh. At that time, the square, previously known simply as place de la Cathédrale, was renamed place Pigneau de Béhaine.

The Pigneau de Béhaine statue was removed during the August Revolution of 1945. The present statue of the Virgin Mary, made of Italian granite and created by sculptor G Ciocchetti, was installed in February 1959.

During the colonial period, a cemetery for French Roman Catholic priests was established immediately behind the Lăng Cha Cả.

This 1968 photograph shows the mausoleum and next to it the main gate of Tân Sơn Nhất Airbase

Towards the end of the French era, urban development began to encroach upon the land surrounding the mausoleum. By the 1960s, as the first American troops arrived, the Lăng Cha Cả was a small compound in the middle of a busy traffic roundabout, right next to the main gate of Tân Sơn Nhất Airbase. However, the South Vietnamese authorities continued to maintain the mausoleum as a national monument right down to 1975.

After reunification, discussions began regarding the repatriation of foreign graves, and in 1983 the mausoleum was earmarked for clearance, along with the old rue de Massiges cemetery (now Lê Văn Tám Park) and several other French military graveyards.

Pigneau’s remains were exhumed, cremated and then delivered to the French Consul General for repatriation, along with the remains of several other priests who had been buried in the adjacent cemetery. Other graves at the site were cleared away. The mausoleum was then demolished to create a large roundabout. Today this roundabout – still known as Lăng Cha Cả – is one of the city’s busiest intersections. A flyover was installed in 2013.

The Dinh Tân Xá at the Archbishop’s Palace

While the Lăng Cha Cả and the statue of Pigneau de Béhaine have long been consigned to history, the Dinh Tân Xá house which Nguyễn Phúc Ánh built for his friend still stands today in the grounds of the Archbishop’s Palace at 180 Nguyễn Đình Chiểu in Hồ Chí Minh City’s District 3. It was dismantled and rebuilt twice, firstly in 1870 in the grounds of the previous bishop’s palace at 6 rue de l’Évêché [6 Alexandre de Rhodes] and 30 years later at its current location. Still used regularly as a private chapel by the Archbishop and his staff, this historic building was dismantled again in 2013-2014 and reassembled on a raised platform to provide further protection against damp and insects.

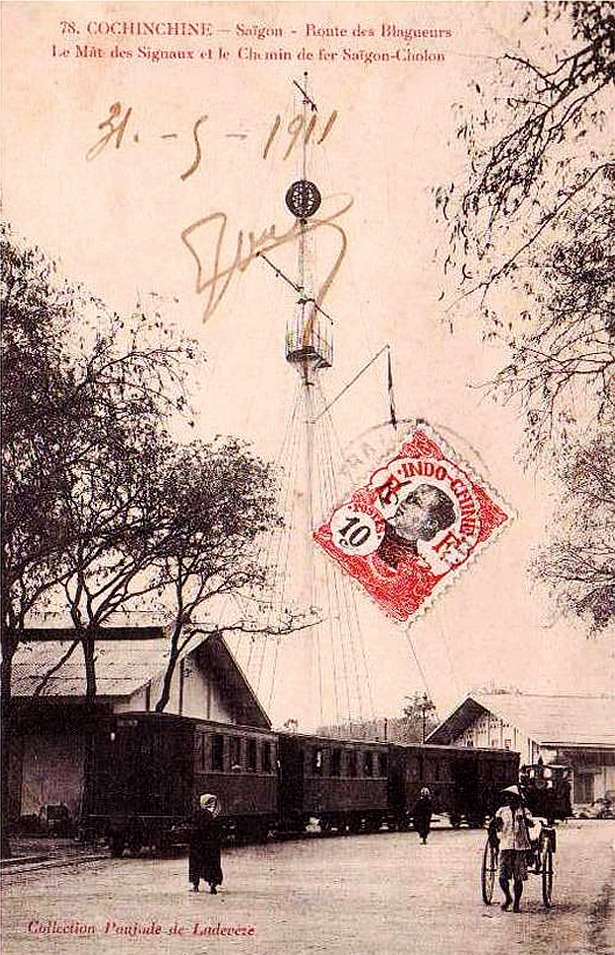

Saigon – The Bishop Pigneau de Behaine Mausoleum, photographed in 1867 by John Thomson (Wellcome Library, London), which was bulldozed by the city authorities in 1983 to make way for the Lăng Cha Cả intersection (11 June 2017)

Saigon – A 1960s shot of the Bishop Pigneau de Behaine Mausoleum (photographer unknown), which was bulldozed by the city authorities in 1983 to make way for the Lăng Cha Cả intersection, and the same view today (14 August 2017)

Saigon – Colonial era postcard of the Bishop Pigneau de Behaine Mausoleum, which was bulldozed by the city authorities in 1983 to make way for the Lăng Cha Cả intersection, and the same view today (1 July 2017)

“Saigon 1968: Entrance to Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Base” (photographer unknown) showing the Pigneau de Behaine Mausoleum, which was bulldozed by the city authorities in 1983 to make way for the “Lăng Cha Cả” intersection, and the same view today (1 August 2017)

A 1960s image of the Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum

Another 1960s image of the Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum (William Price)

A 1966 aerial shot of the Pigneau de Béhaine mausoleum and behind it the French cemetery; the pre-1975 Tân Sơn Nhất Airbase main gate may be seen on the lower right of the picture

The urn containing the ashes of Pigneau de Béhaine after they were returned to the Paris Foreign Missions Society in 1983

The busy roundabout which occupies the site today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.