231-501 waits to depart from Phnom Penh station

This article was published previously in Saigoneer http://saigoneer.com

A brief digression from the usual Việt Nam-focused articles – joining a group of British steam enthusiasts visiting Phnom Penh as part of a PTG rail tour, travelling behind Toll Royal Railway’s preserved “Pacific” steam locomotive and catching up with developments on the Cambodian rail scene…..

A “photo run-past” at Pochentong

While Vietnam Railways currently has little to offer the steam train enthusiast, its Cambodian counterpart, Toll Royal Railway, has been offering special steam-hauled charter trains to foreign enthusiast groups for several years, as a sideline to its burgeoning freight business.

The involvement of Australian company Toll Holdings in the Cambodia railway sector dates from 2009, when the Royal Government of Cambodia outsourced its railway operations to that company under a 30-year exclusive concession. Since that time, operating under the name Toll Royal Railway and with funding from ADB and AusAID, Toll has embarked on an ambitious US$143 million project to rehabilitate the entire Cambodian rail network.

Refurbished Alsthom diesel locomotive BB-1053 shunting at Phnom Penh (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

The 254km South Line from Phnom Penh to Kampong Som (Sihanoukville) was reopened in 2012 and work is currently under way to rehabilitate the 388km North Line from Phnom Penh to Poipet, as well as the 48km link from Poipet to Sisophon, which it is envisaged will eventually serve cross-border traffic to and from Thailand.

The railway in Cambodia was one of the last to be built in French Indochina. Paid for by German war reparations and originally operated as a franchise, the North Line opened in 1933 as a 330km route from Phnom Penh to Monkolborey. It was returned three years later to the colonial government and operated for the remainder of the colonial era as a branch of Chemins de fer de l’Indochine (CFI), managed from CFI’s Saigon headquarters – controversially permitting CFI to filch all of the Cambodian railway’s powerful German locomotives for use on Việt Nam’s newly-opened Transindochinois!

Powerful Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG (Hanomag) 2-10-0 “Decapods,” supplied through war reparations, ran the line until they were filched by CFI for the opening of Việt Nam’s Transindochinois (North-South line) in 1936

Plans to link the line with the Vietnamese rail network via Saigon were definitively abandoned in 1938, but in that same year, work began to connect Battambang with the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet, via Poipet. This was achieved by the Thai authorities in 1941, but in subsequent decades, due to the ever-volatile political and military situation, the cross-border link was exploited only intermittently. In the 1970s, the Khmer Rouge removed the track west of Sisophon.

Following independence in 1954, the port of Sihanoukville (Kampong Som) was developed to reduce reliance on Saigon and Khlong Toei (Bangkok), and in 1960 work began with French, West German and Chinese assistance to build the new South Line to connect Sihanoukville with the capital. This opened in November-December 1969, but ceased operations just a few years later as the country descended into war.

The “bamboo railway” (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

Rail services on the North Line resumed in the early 1980s, but warfare and neglect had left the network in a delapidated state. With train services so few and far between, the line became known internationally as the “bamboo railway,” because local people used it to travel on makeshift motorised trollies topped with bamboo platforms.

At present, the Toll Royal Railway is an exclusively freight-focused operation, with a daily quota of two container trains, one coal train and one fuel train travelling the newly-rehabilitated South Line, which reopened in December 2012.

The North Line is currently operational as far as Bat Doeung (km 31) and freight services will be inaugurated later this year.

Refurbished Waggonfabrik 2-car DEMU (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

However, only 48km of the Bat Doeung-Sisophon (km 337) section has so far been rebuilt. Beyond Sisophon, the line to the Thai border has already been relaid and the State Railway of Thailand (SRT) is said to be reinstating the derelict/missing 6km of track from Aranyaprathet to the border.

With its two new 1,300hp Chinese Qishuyan diesels and expanding fleet of refurbished locomotives, Toll has plans to develop its existing freight services and in the longer term also to reintroduce passenger trains on both lines. These plans will undoubtedly take on increased significance in the context of the proposed Trans-Asia Railway (TAR) and Singapore-Kunming Rail Link (SKRL) schemes to create continuous rail links between Singapore and China, reducing passenger and freight transit times and costs between countries in the region and opening up the possibility of a direct rail route from Asia to Europe and Africa.

An entire section of Phnom Penh Depot is still occupied by rusting ex-CFI “Mikado,” “Pacific” and “Mogul” steam locomotives (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

One interesting consequence of the decades of neglect is that, unlike their counterparts here in Việt Nam, the Cambodian rail authorities never got round to scrapping their old French steam locomotives.

Today, an entire section of Phnom Penh Depot is occupied by rusting ex-CFI “Mikados,” “Pacifics” and “Moguls” and the management at Toll has had the foresight to restore one of these – SACM Graffenstaden 4-6-2 “Super Pacific” No 231-501 – to full working order for steam charters. Sadly, the economics of running live steam means that these charters are currently available only to large pre-booked groups, but with heritage railways growing increasingly popular around the world (there are 108 privately-run steam railways in the UK alone), there can be little doubt that demand for the old engine’s services will continue to grow.

A “photo run-past” at Phlov Bambaek junction near Samrong, where the North and South Lines bifurcate

The seven-hour trip out of Phnom Penh Station behind 231-501 covers just 44km along the Kompong Som (Sihanoukville) port line and back, with accommodation provided in the 1932-built former royal coach of King Sisowath Monivong. The train runs at what can only be described as a stately pace, stopping obligingly for “photo run-pasts” at Phnom Penh Depot, Pochentong, Psah C-7, Oedom “Dry Port” container terminal, and Phlov Bambaek junction near Samrong, where the North and South Lines bifurcate. Reaching a loop line at Komar Reachea, the locomotive is transferred to the other end of the train for its return journey, tender first, to Phnom Penh.

As planners everywhere strive for faster and more modern forms of transportation, it seems that nothing can diminish the global appeal of the steam locomotive, that slow, old, yet gloriously nostalgic reminder of our industrial heritage.

231-501 waits to depart from Phnom Penh

Accommodation on steam charters is provided in the 1932-built former royal coach of King Sisowath Monivong

A “photo run-past” at Pochentong

Container wagons at Phnom Penh Station (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

A “photo run-past” at Phlov Bambaek junction near Samrong, where the North and South Lines bifurcate

One of Toll Royal Railway’s new Qishuyan BB-1061 locomotives (photo courtesy Toll Royal Railways)

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

You may also be interested in these articles on the railways and tramways of Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos:

A Relic of the Steam Railway Age in Da Nang

By Tram to Hoi An

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building

Derailing Saigon’s 1966 Monorail Dream

Dong Nai Forestry Tramway

Goodbye to Steam at Thai Nguyen Steel Works

Ha Noi Tramway Network

How Vietnam’s Railways Looked in 1927

Indochina Railways in 1928

“It Seems that One Network is being Stripped to Re-equip Another” – The Controversial CFI Locomotive Exchange of 1935-1936

Phu Ninh Giang-Cam Giang Tramway

Saigon Tramway Network

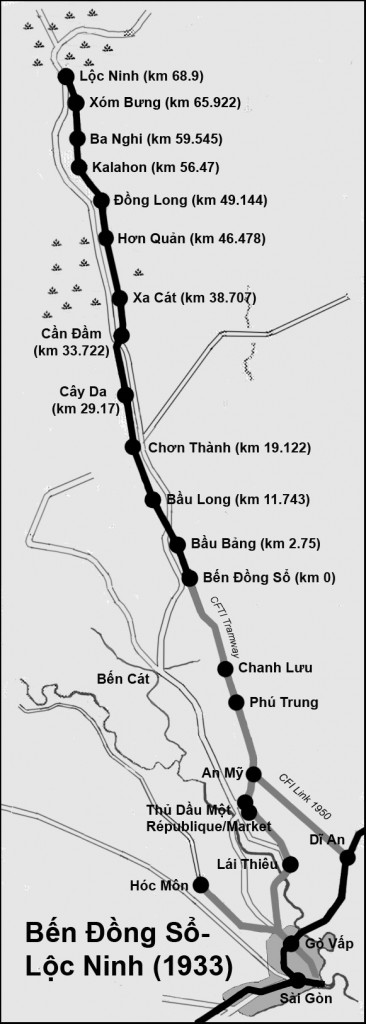

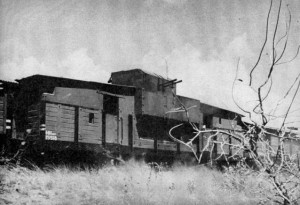

Saigon’s Rubber Line

The Changing Faces of Sai Gon Railway Station, 1885-1983

The Langbian Cog Railway

The Long Bien Bridge – “A Misshapen but Essential Component of Ha Noi’s Heritage”

The Lost Railway Works of Truong Thi

The Mysterious Khon Island Portage Railway

The Railway which Became an Aerial Tramway

The Saigon-My Tho Railway Line