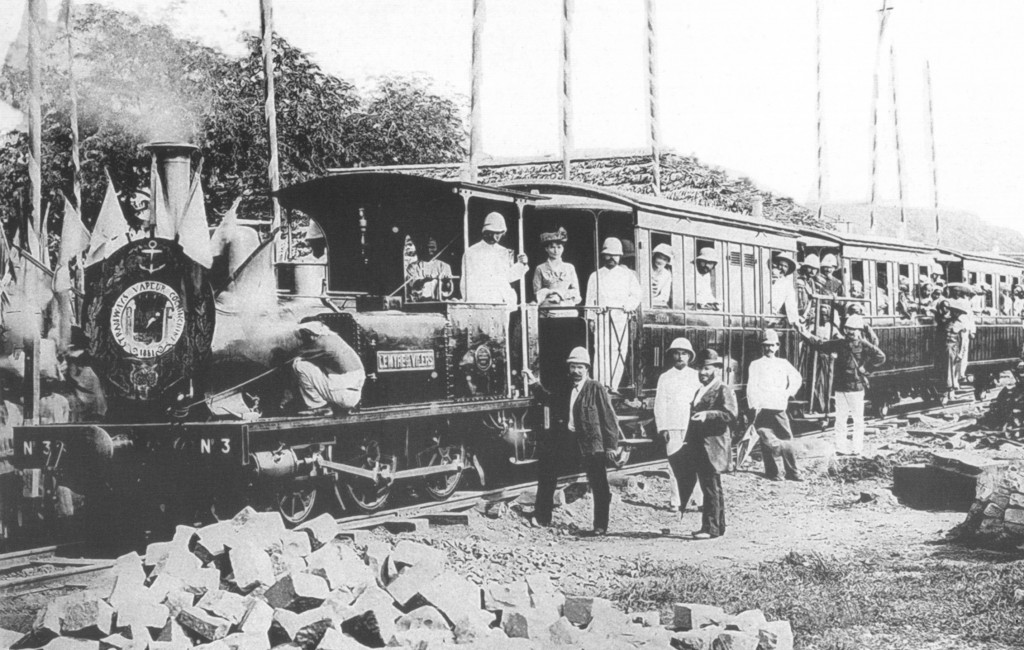

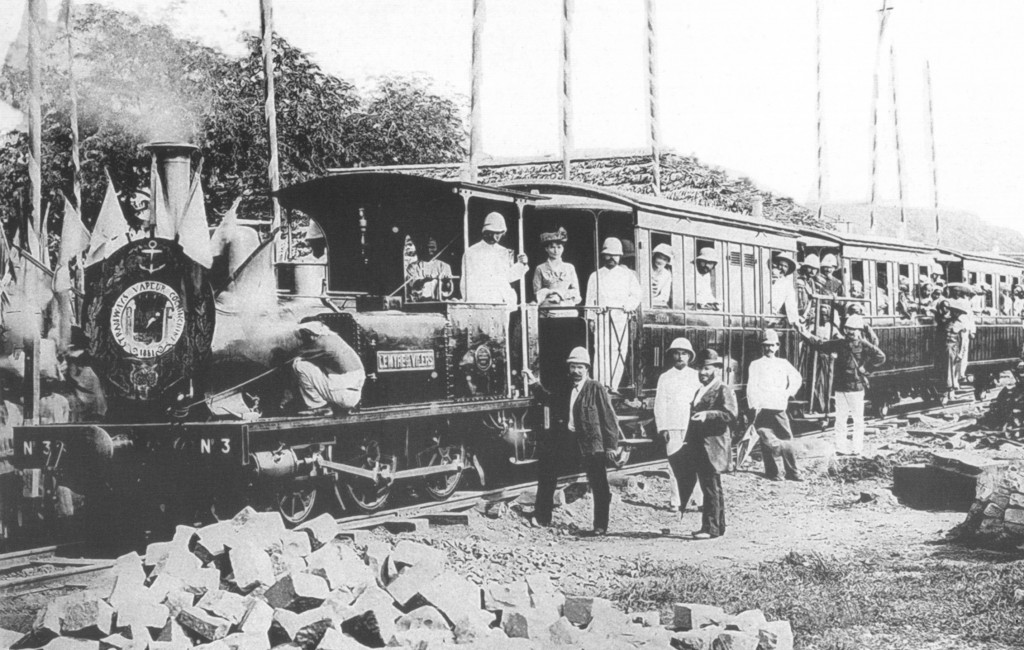

The grand opening of the Saigon–Chợ Lớn “high road” steam tramway line on 27 December 1881

As ever-increasing levels of traffic congestion and air pollution turn many of Hồ Chí Minh City’s road junctions into choking bottlenecks, many hopes are pinned on plans to construct a new urban railway network in the southern metropolis. Yet urban railways are hardly a new concept in this city, which was once home to one of Southeast Asia’s largest urban tramway networks.

Indochina’s first mechanised rail-guided transportation system was the 1m-gauge Saigon–Chợ Lớn “high road” steam tramway, operated by the Société générale des tramways à vapeur de Cochinchine (SGTVC) and opened to the public on 27 December 1881.

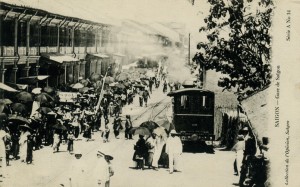

CFTI’s original 0.6m gauge Decauville tramway pictured in 1891

Ten years later, the Compagnie française des tramways de l’Indochine (CFTI) established a rival steam-hauled tramway line from Saigon to Chợ Lớn, which followed the “low road” along the north bank of the Bến Nghé Creek.

In 1895, the CFTI extended its tramway northwards from Saigon to Gò Vấp, but the company soon discovered that its initial choice of 0.6m gauge Decauville equipment had been a costly mistake – beset by technical problems and obliged to replace all of its track and rolling stock, the company was declared bankrupt in 1896.

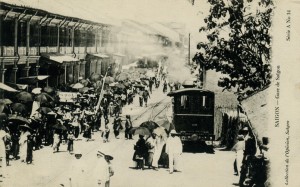

Saigon Tramway Station in the 1890s

However, the Colonial Council approved a generous refinancing arrangement and in subsequent years the company was transformed into a highly profitable operation which left SGTVC struggling to compete on the Saigon-Chợ Lớn route.

Indeed, so remarkable was the CFTI’s financial turnaround that between 1899 and 1906 it was able to afford a costly regauging of its entire network from 0.6m to 1m, and also to build an 800m slip road linking its Gò Vấp tramway station with the newly-built Saigon–Nha Trang railway line.

Other new lines followed, from Gò Vấp to Hóc Môn in 1904 and from Gò Vấp to Lái Thiêu in 1913. However, plans drawn up in 1912 to electrify the CFTI network and re-route tramway services through the city centre were delayed by war in Europe and not put into effect until 1923.

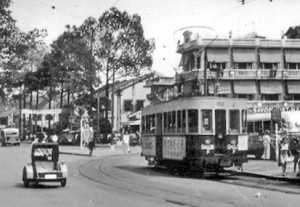

A Galliéni line tram in Chợ Lớn in the 1940s

The dynamic growth of CFTI during this period was in stark contrast to the declining fortunes of SGTVC, which lost its Saigon–Chợ Lớn “high road” steam tramway franchise in 1911. The line then reverted to government control, becoming a run-down and loss-making component of the main-line Réseaux non concédés, but in 1925 it was acquired by CFTI and rebuilt as an electric tramway connecting Saigon and Chợ Lớn via the newly opened boulevard Galliéni (Trần Hưng Đạo boulevard).

In 1927-1929 the CFTI extended its network further from Lái Thiêu to Thủ Dầu Một, electrified the Gò Vấp-Lái Thiêu-Thủ Dầu Một and Gò Vấp-Hóc Môn lines and extended the “low road” tramway line west to Chợ Lớn’s Bình Tây Market.

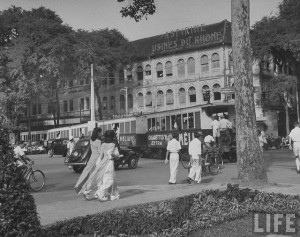

Another Galliéni line tram in Chợ Lớn in the late colonial era

During the same period, the company also began work on a further extension from Thủ Dầu Một to Bến Đồng Sổ, entering into a lucrative partnership with the Compagnie des voies ferrées de Lộc Ninh et du centre Indochinois (CVFLNCI) whereby freight trains on their new rubber plantation line from Lộc Ninh to Bến Đồng Sổ could use CFTI metals to access Saigon port – for more details, see Saigon’s Rubber Line. When that new branch opened in 1933, CFTI also secured the concession to run passenger services on behalf of CVFLNCI, thereby adding a further 69km to its existing 87km operational network.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the CFTI shrewdly diversified its operations to ensure that it also controlled the greater part of the city’s bus services.

A CFTI electric tram circumnavigates the municipal theatre in the 1940s

However, both its tram and bus systems suffered serious damage during the Allied aerial bombing of 1943-1945 and the subsequent August Revolution of 1945. The events of the First Indochina War and the lawlessness occasioned by the Bình Xuyên organised crime syndicate in the early 1950s impacted heavily on CFTI revenue and in the period from 1950-1954 the company gradually closed its tramway lines and also threatened the withdrawal of bus services unless the government reviewed the terms of its contract.

In response, the Ministry of Public Works terminated CFTI’s franchise on 10 November 1956, at the same time announcing that the trams would be “abolished permanently and replaced by buses.” By 1957 the entire Saigon tramway system was no more.

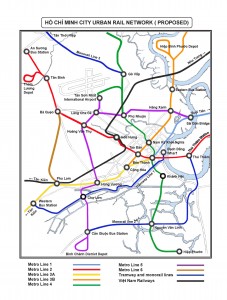

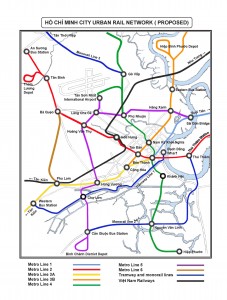

The planned Hồ Chí Minh City Urban Rail Network

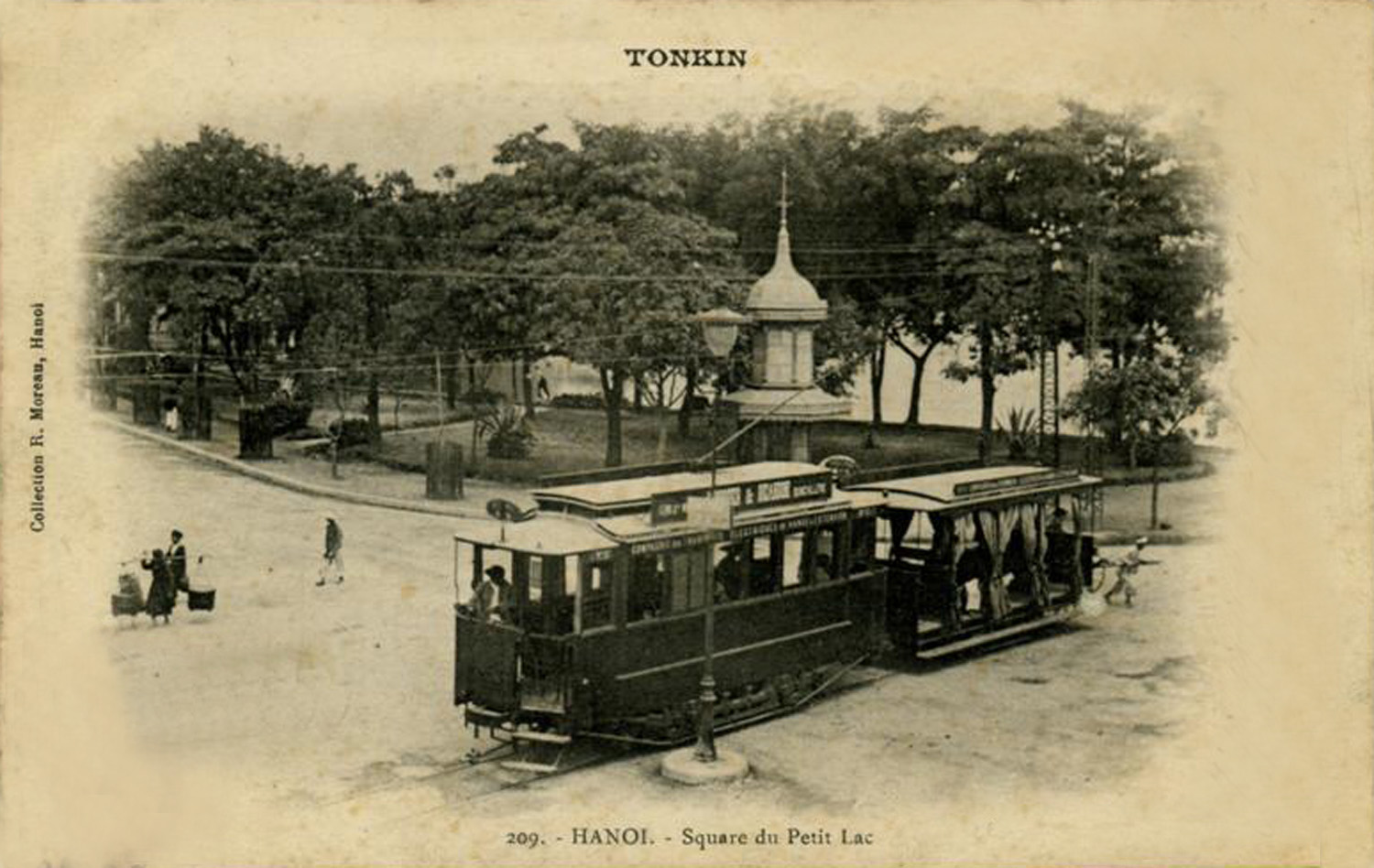

Unlike in Hà Nội, where electric trams soldiered on until as late as 1989 (see Hà Nội Tramway Network), it is now nearly 60 years since the Saigon tramway network was deemed surplus to requirements.

In some countries of the world, old tramway systems like that of Saigon have survived and still operate today much as they did when they were first built over a century ago. In others, new modern tramway systems have been created which run along public streets as well as on segregated sections of track.

However, in Việt Nam, with its more relaxed sense of road discipline, plans for new urban railway systems in both Hồ Chí Minh City and Hà Nội have thus far focused on a combination of underground and overhead light railway systems – which wisely keep running track at arm’s length from the chaos on the streets.

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

You may also be interested in these articles on the railways and tramways of Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos:

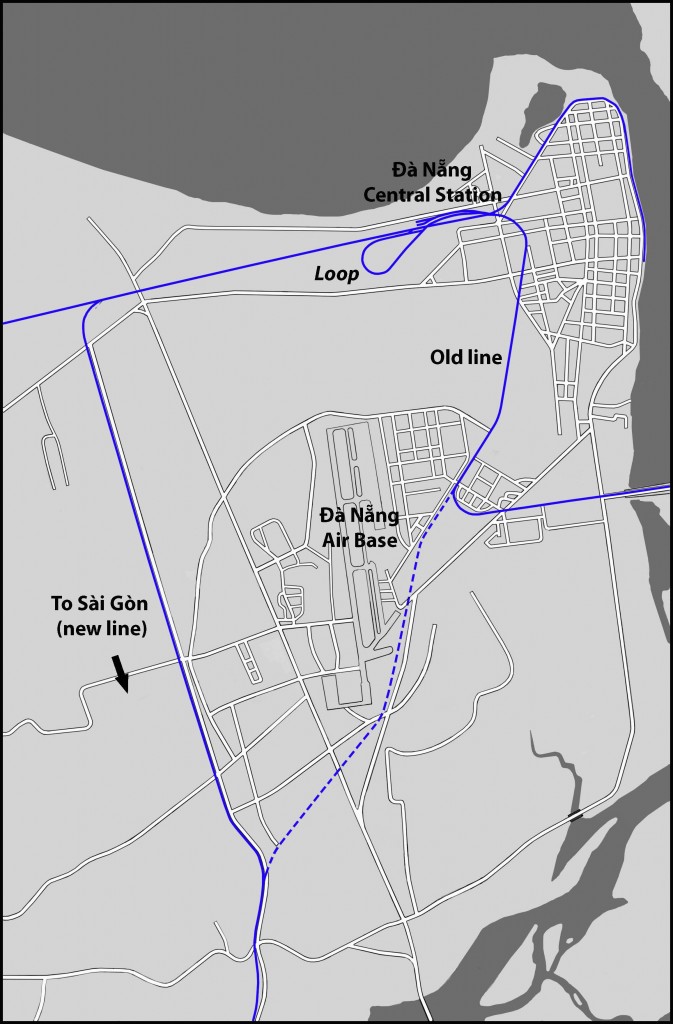

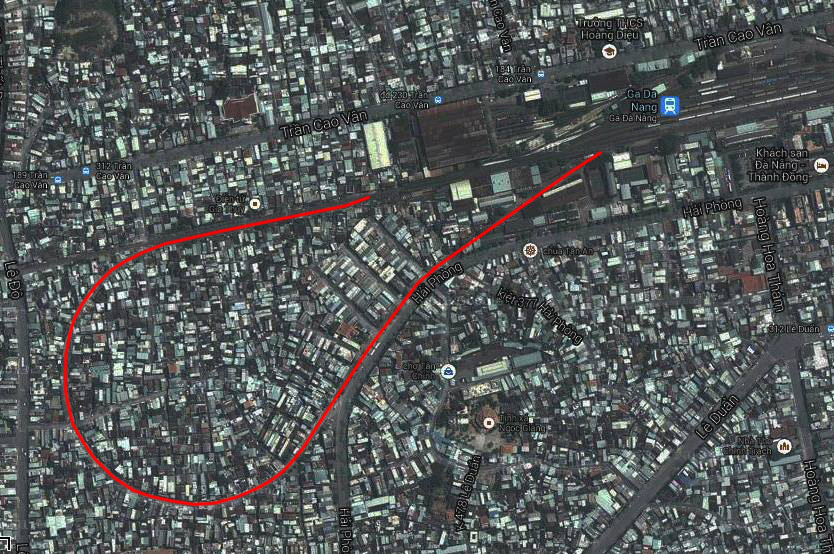

A Relic of the Steam Railway Age in Da Nang

By Tram to Hoi An

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building

Derailing Saigon’s 1966 Monorail Dream

Dong Nai Forestry Tramway

Full Steam Ahead on Cambodia’s Toll Royal Railway

Goodbye to Steam at Thai Nguyen Steel Works

Ha Noi Tramway Network

How Vietnam’s Railways Looked in 1927

Indochina Railways in 1928

“It Seems that One Network is being Stripped to Re-equip Another” – The Controversial CFI Locomotive Exchange of 1935-1936

Phu Ninh Giang-Cam Giang Tramway

Saigon’s Rubber Line

The Changing Faces of Sai Gon Railway Station, 1885-1983

The Langbian Cog Railway

The Long Bien Bridge – “A Misshapen but Essential Component of Ha Noi’s Heritage”

The Lost Railway Works of Truong Thi

The Mysterious Khon Island Portage Railway

The Railway which Became an Aerial Tramway

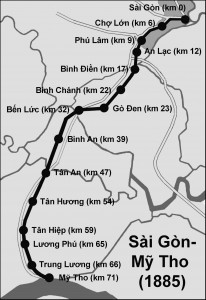

The Saigon-My Tho Railway Line