Marred by the usual colonial condescension and obvious ignorance of Vietnamese art and architecture, this French article of 1902 is published here in translation only for its interesting historic references and intriguing images

Indo-China has experienced a definitive rise under the impetus of a very talented governor, Paul Doumer.

The visitor to the Exposition in Hanoï will find him there in person, revealing in striking form the path which has been travelled since the conquest in the fields of arts, commerce and industry. Listening to his words will surely awaken in the visitor more extensive curiosity.

In particular, this visitor will not want to stick with his first plan of travel, cautiously limited to the immediate attractions directly dependent on the Exposition itself. He or she will have an ardent desire, before returning to France, to go and see some old things of this empire of Annam which have yet to sink beneath the civilising tide. An excursion to Hue should at the top of any redesigned and expanded travel itinerary.

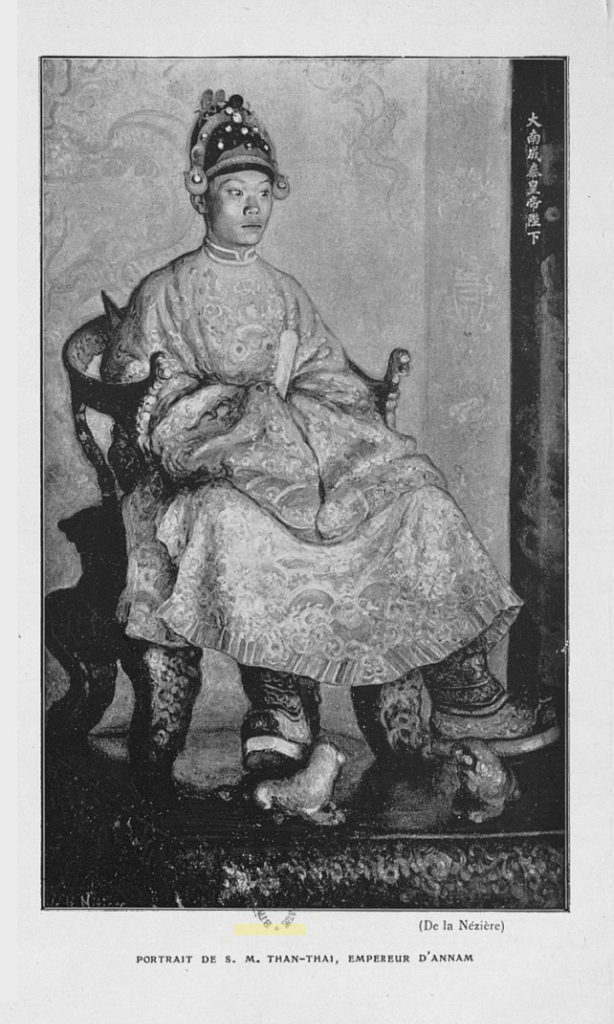

In November 1901, a special meeting of the Conseil supérieur de l’Indo-Chine was convened in the palace of the Council of Ministers of His Majesty Emperor Thanh-Thai in Hue. No doubt Governor Doumer wished to close his five years of government with a significant ceremony at the very heart of his vast colonial domain, now definitely conquered and pacified, and ready to receive the fruitful seeds of his labours.

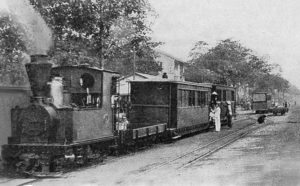

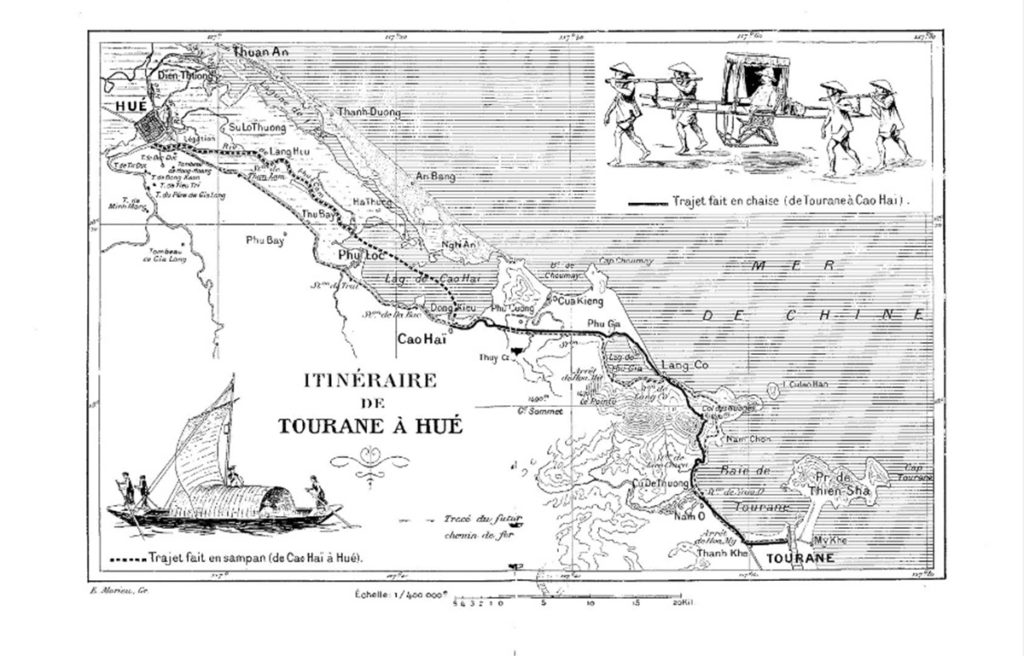

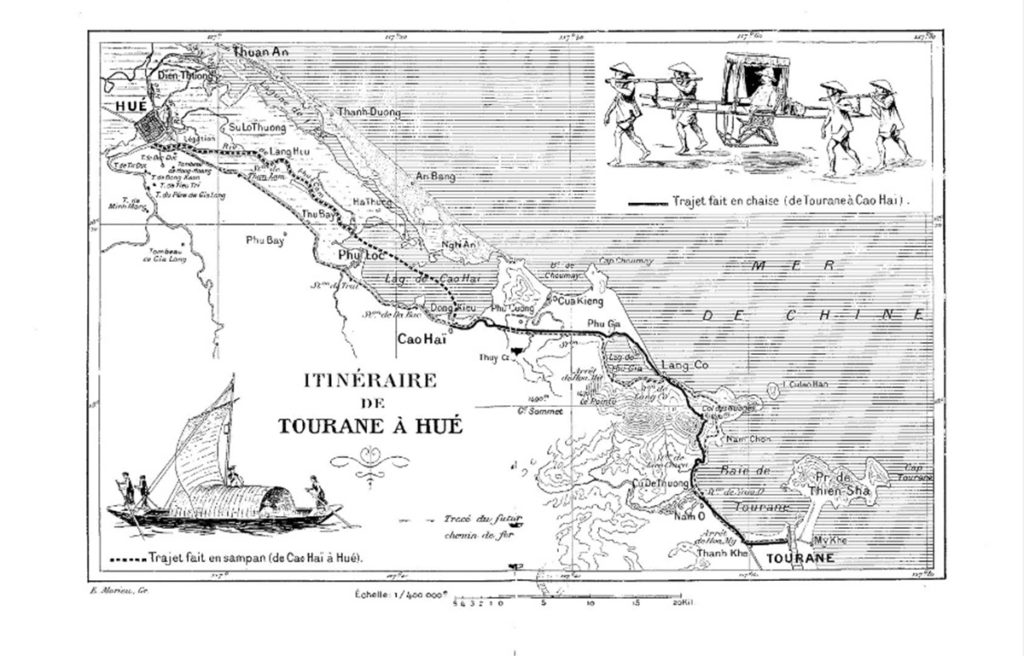

Already on the road from Tourane to Hue, which passes through the picturesque Pass of Clouds, one meets large teams of diggers and road workers. Their main “points of attack” are the new tunnels located on the flanks of granite rocks clothed with wild vegetation. The local tram (chair carrier) agonises about the future of his job; he will be replaced, before two years are out, by new rails and locomotives.

Whether coming from Hanoï or Saïgon, you must land in Tourane. One joyfully embarks from the little steamer of the Messageries maritimes after what can be a rough passage through the Tonkinese gulf. One rides by chair for a full day, viewing picturesque sights which are a joy to the eyes. Lunch is served in the village of Lang-Co. In the evening, after a few last kilometres travelled by night in the light of torches in order to scare off marauding tigers, one reaches Cao-Haï, where dinner is served. Then one settles in comfortable sampans to pass a restorative night, rocked very softly on the waters of the great lagoon. The next morning, one arrives in Hue, eager for excursions and strolls, ready to hunt for the trinkets which very well-informed merchants hold in reserve for the tourists of distinction.

A stay between two journeys by courier vessel leaves five or six days to be spent in Hue and its environs. This is sufficient.

The “places to see” are spread out at various distances, permitting visitors to undertake small, medium and large days of tourism. One returns at the end of each day satisfied and not weary, finding again with pleasure those pacifying sampans on the great lagoon.

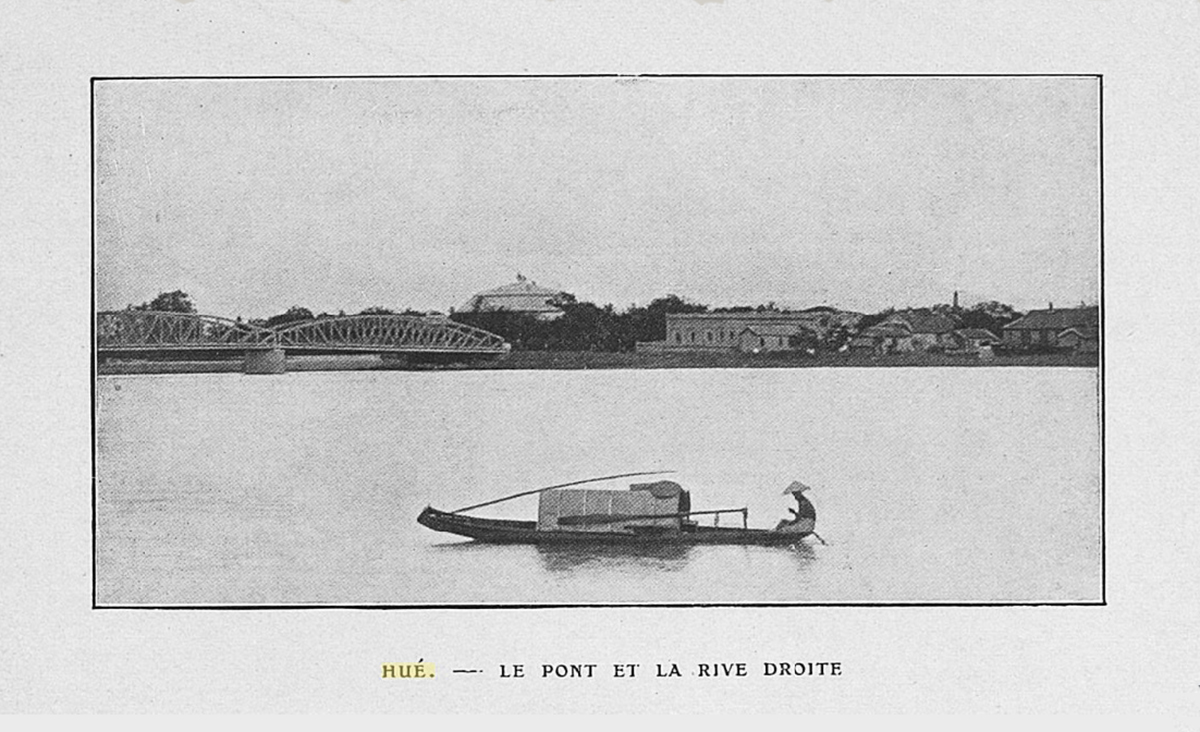

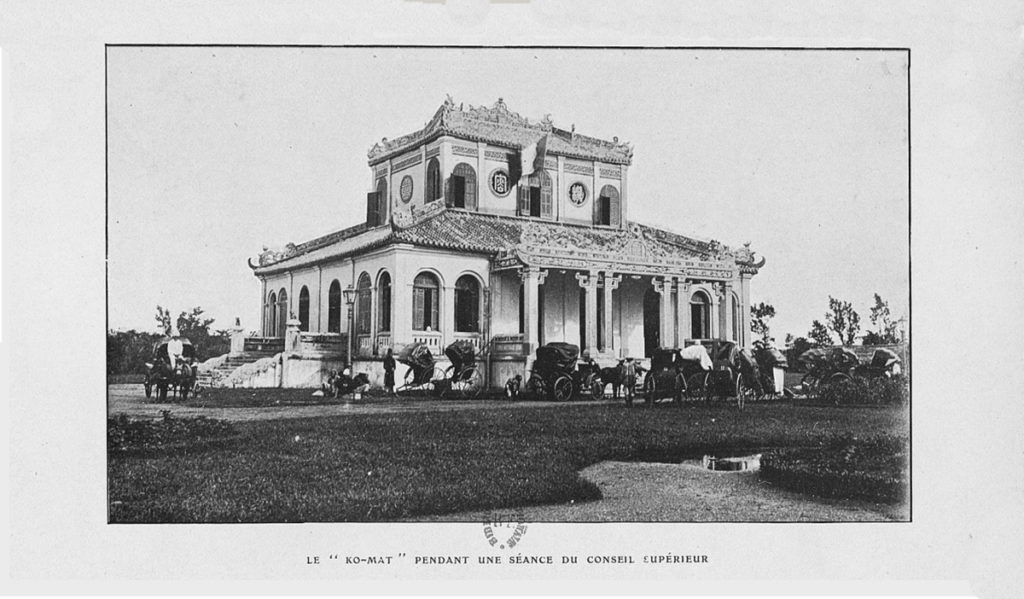

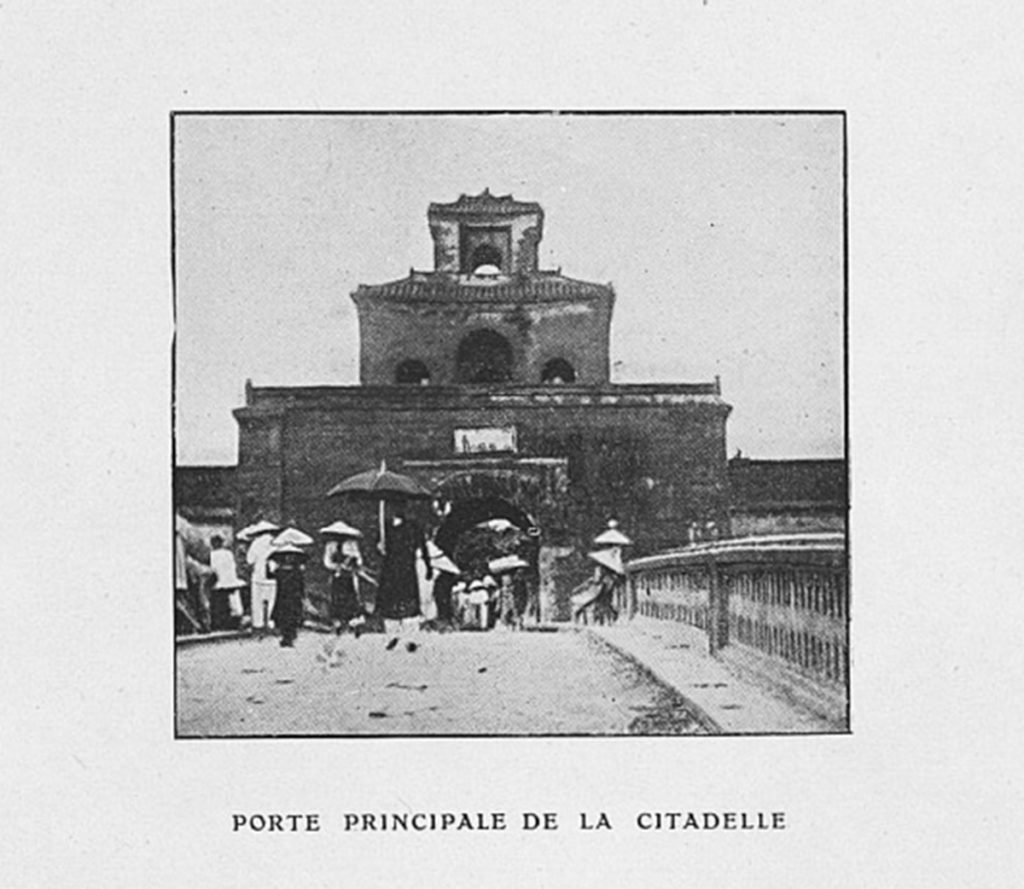

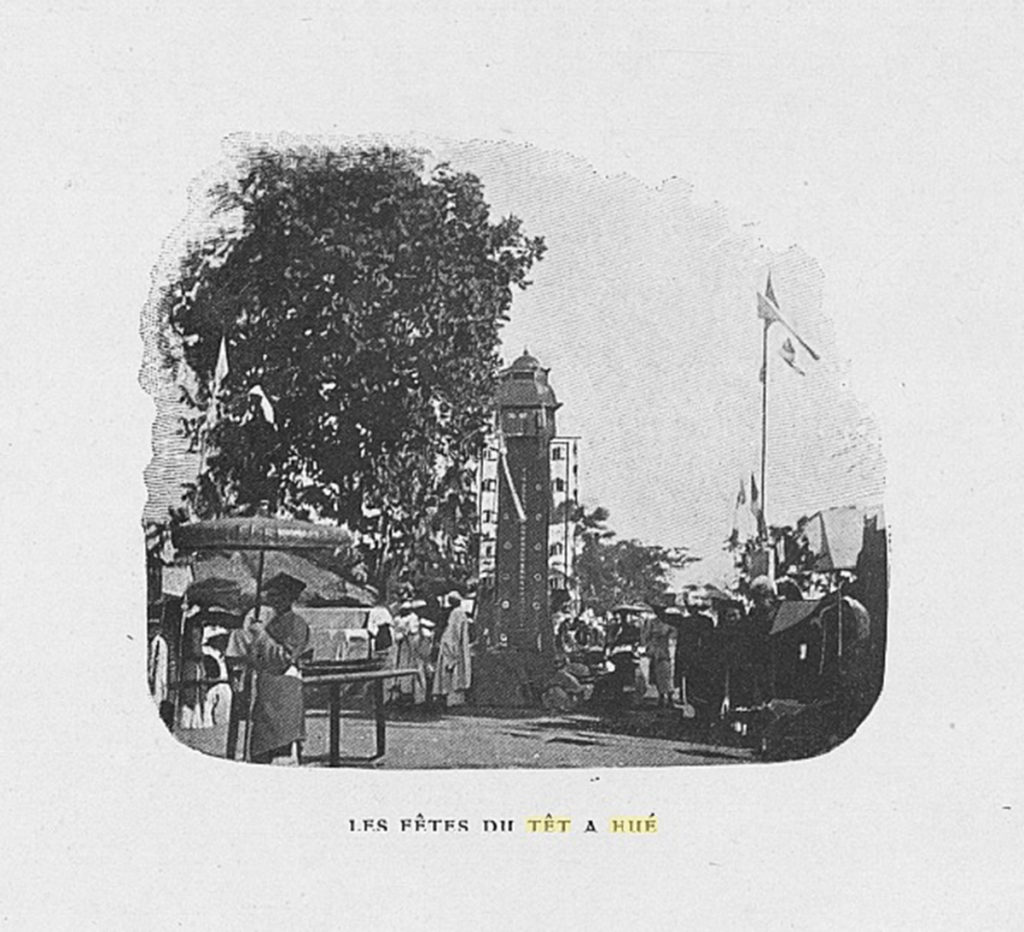

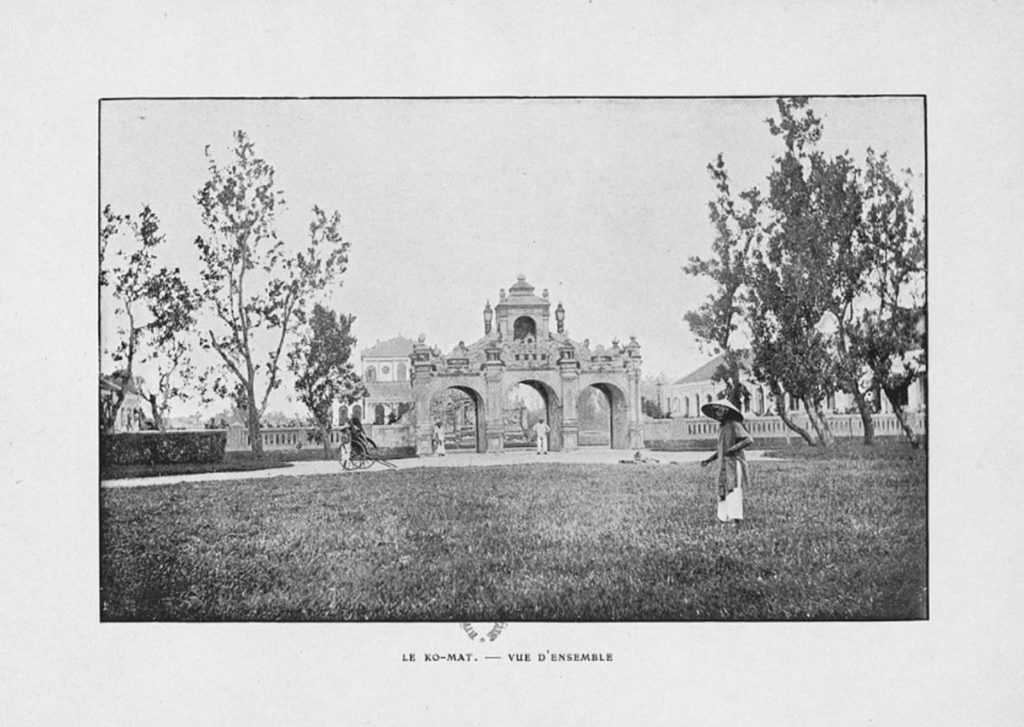

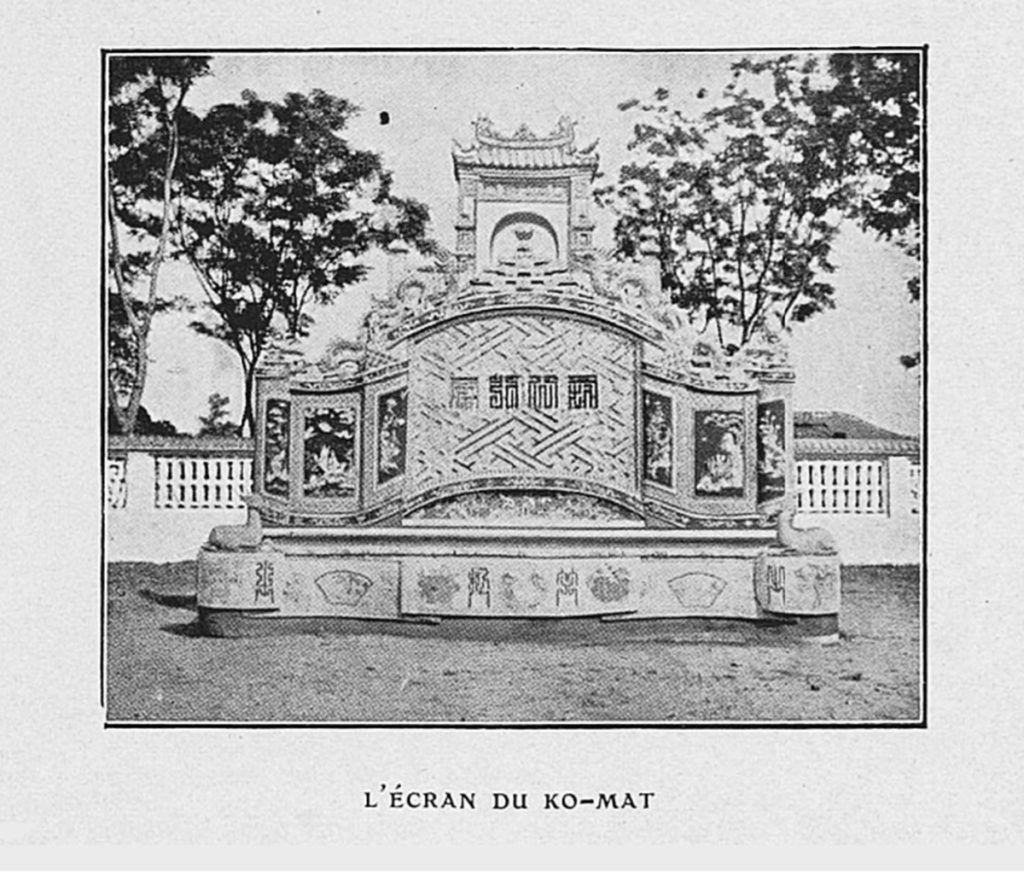

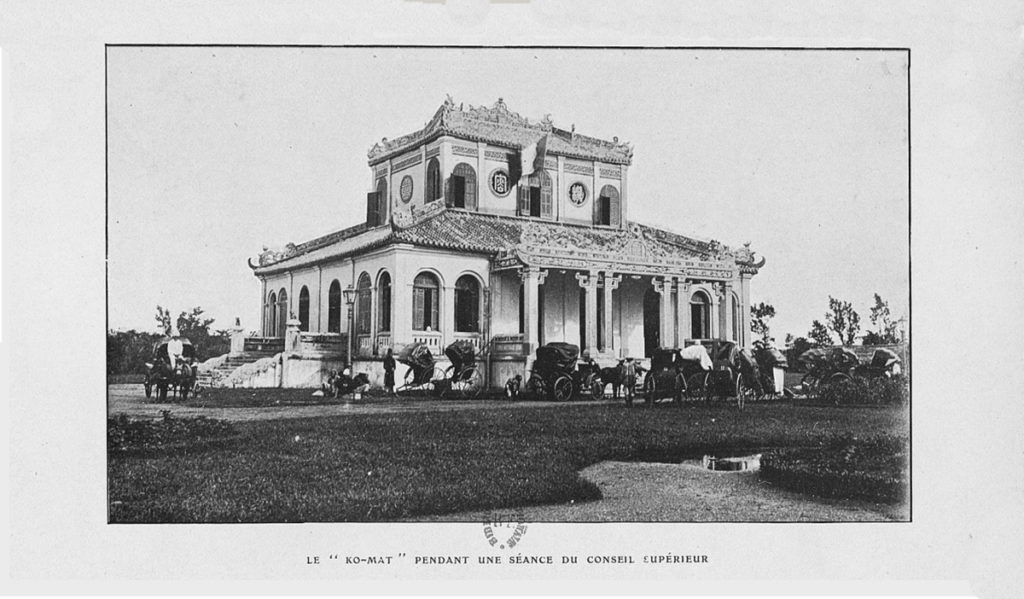

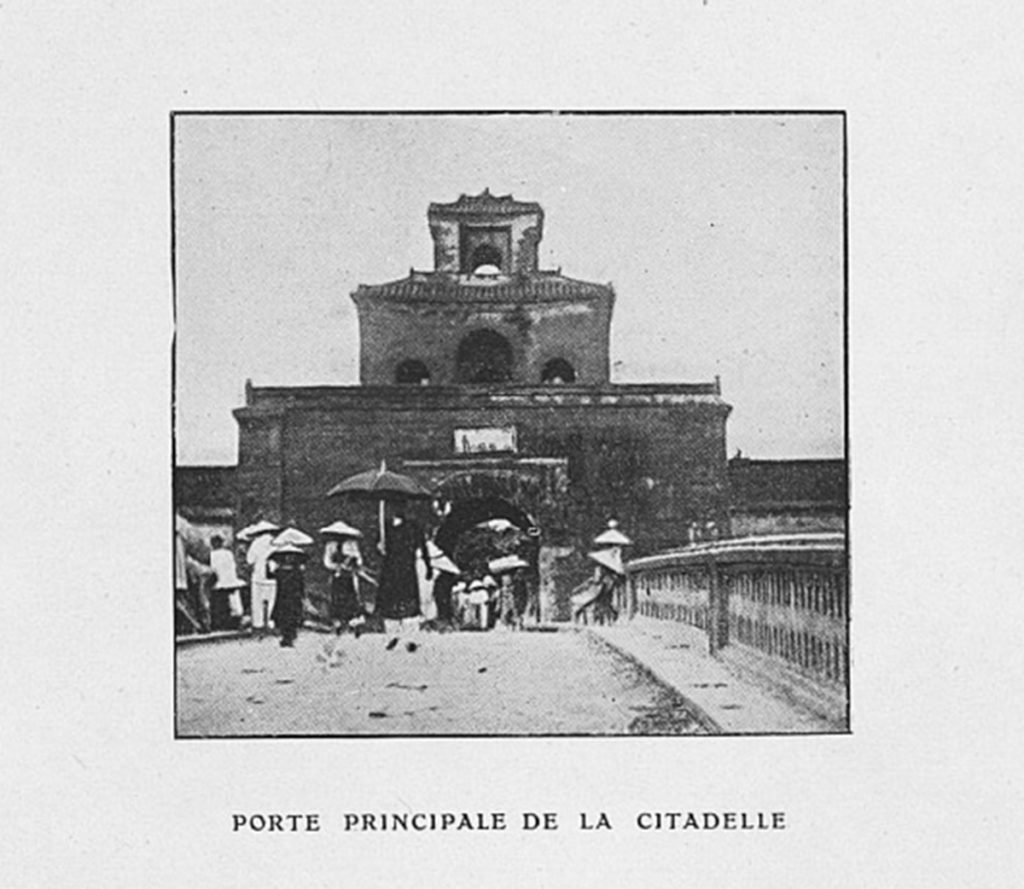

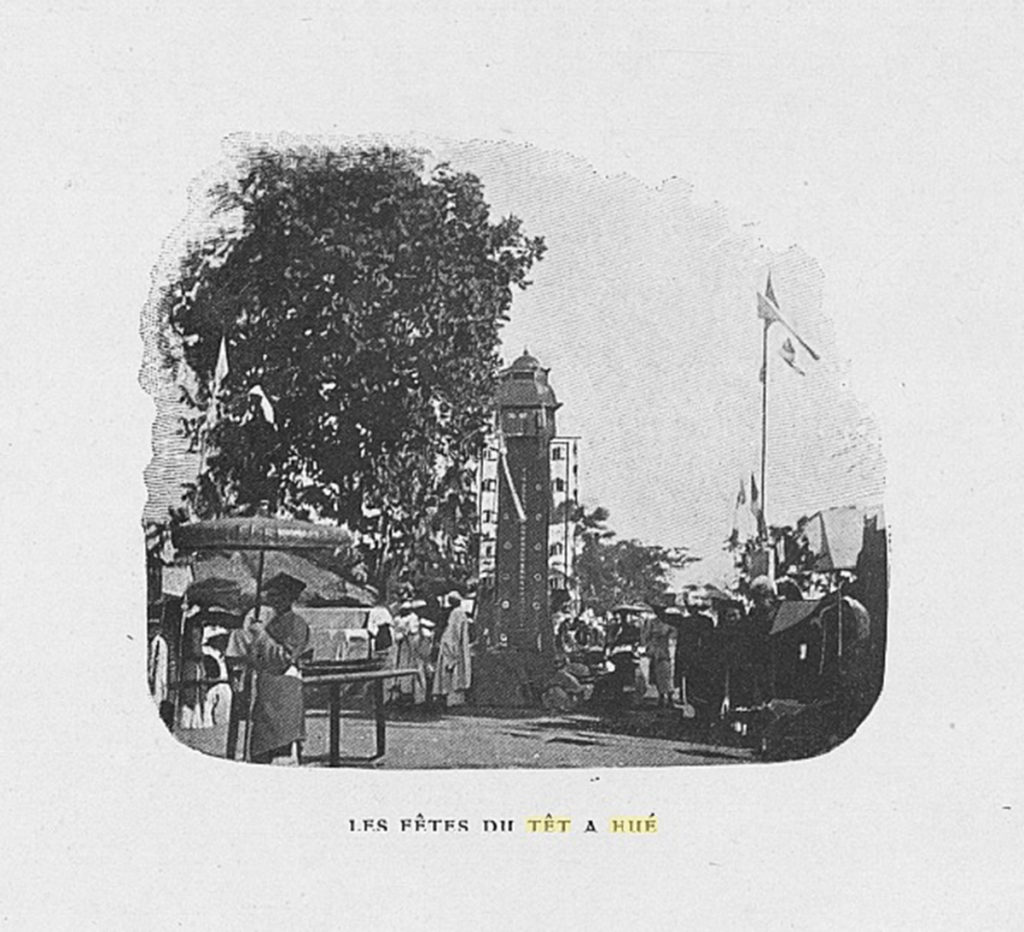

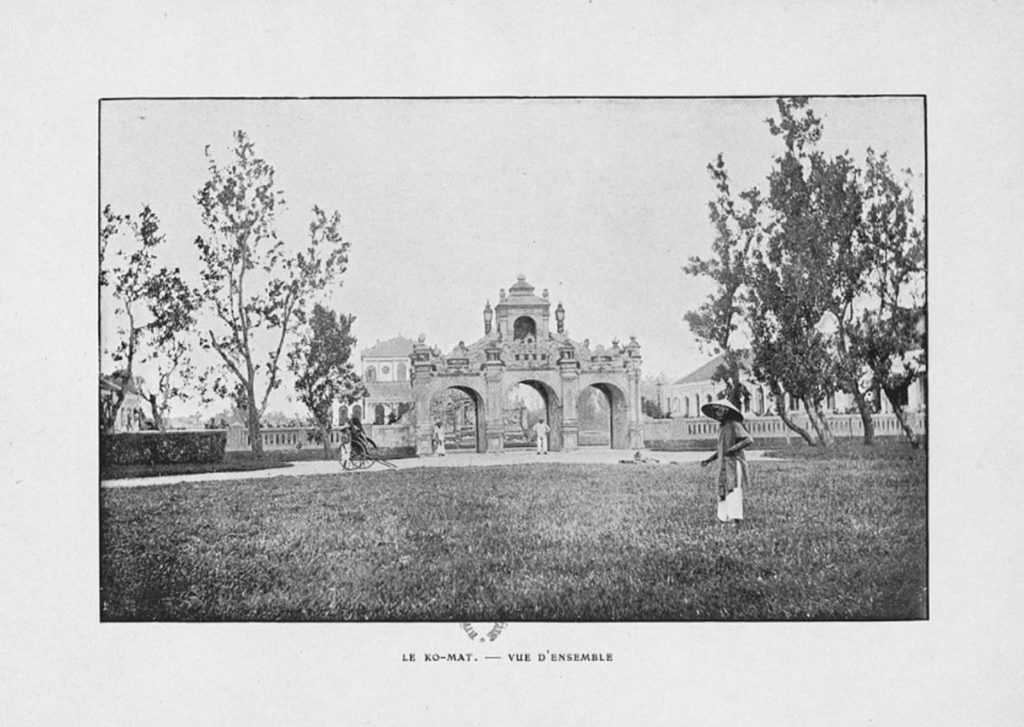

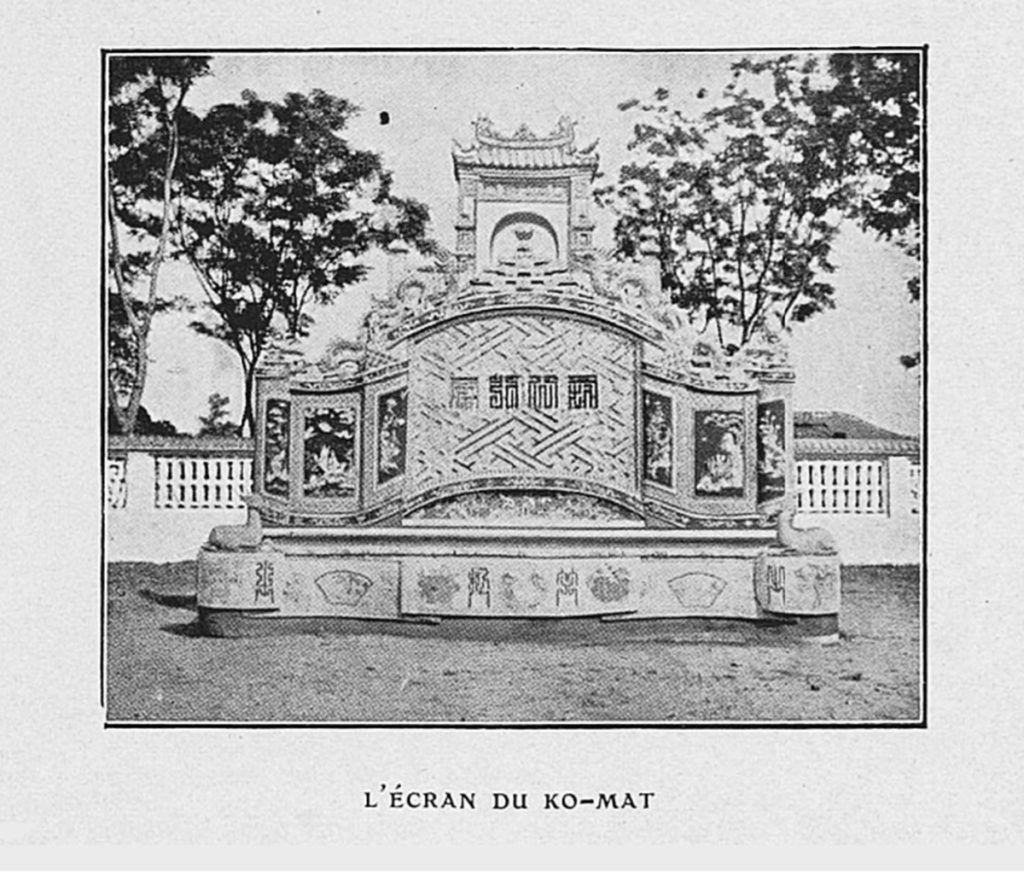

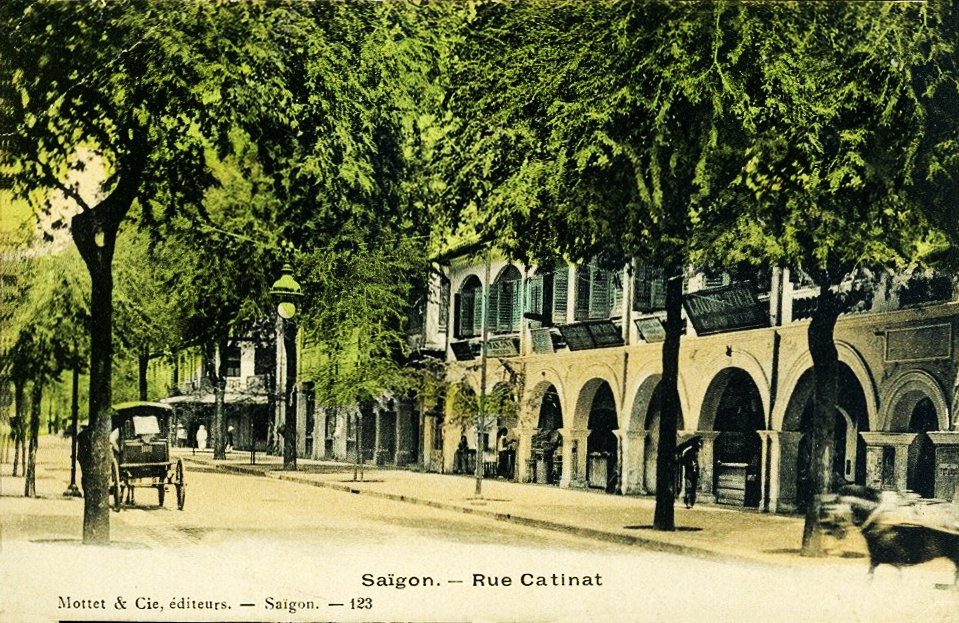

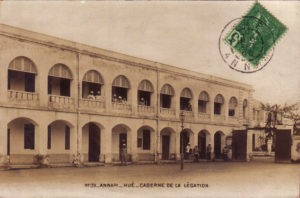

Properly speaking, Hue is not yet a city. Situated on the left bank of the pretty and gracefully named Perfume River, one will find here a vast Citadel, built about a century ago by a mission of French officers in the most exact Vauban style. Within its enclosure there are some basic elements: first, the vast Palace compound, dotted with pagodas, outbuildings, gardens and mandarin dwellings. Then the Co-Mat or Council of Ministers, the School of Agriculture, and the barracks of the Naval Infantry Battalion which holds garrison here. Against the brown walls of the fortress lies a swarming and fragrant Asiatic agglomeration, where, as everywhere in Indo-China, the Chinese control the bulk of traffic and wealth.

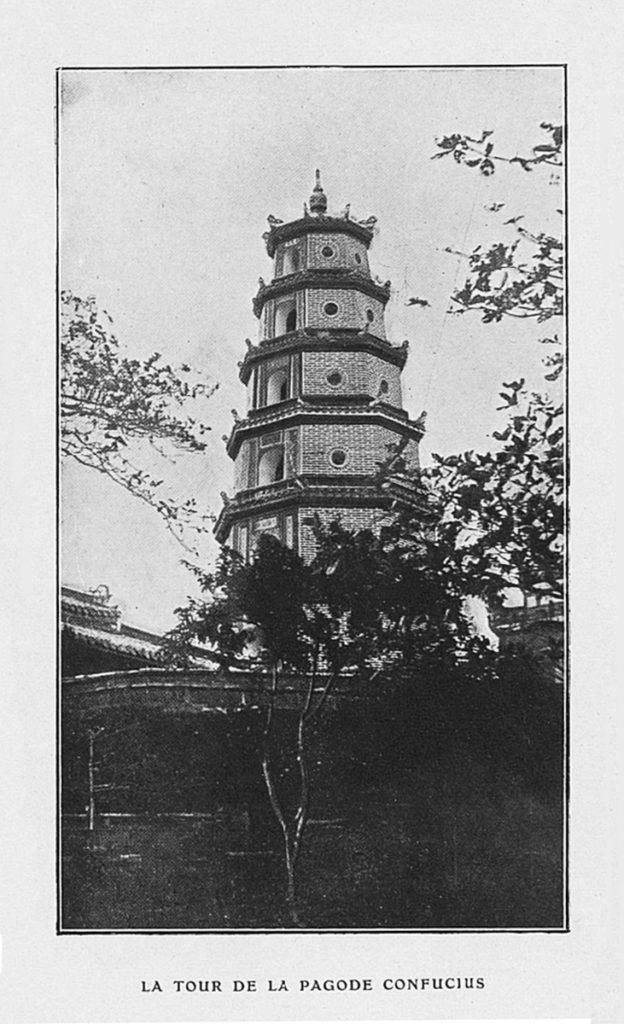

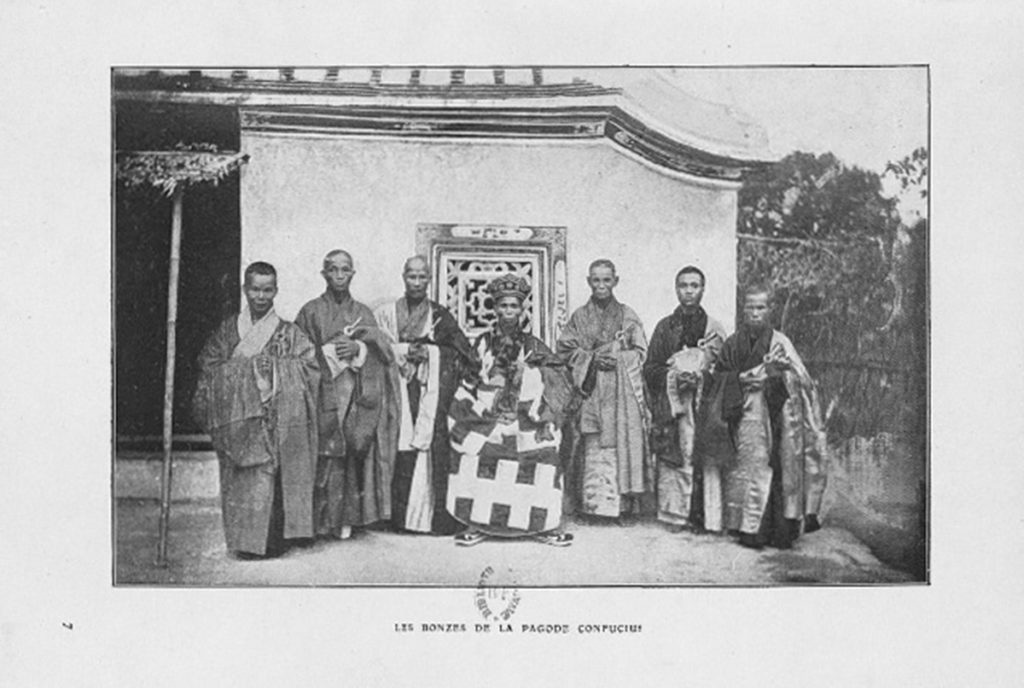

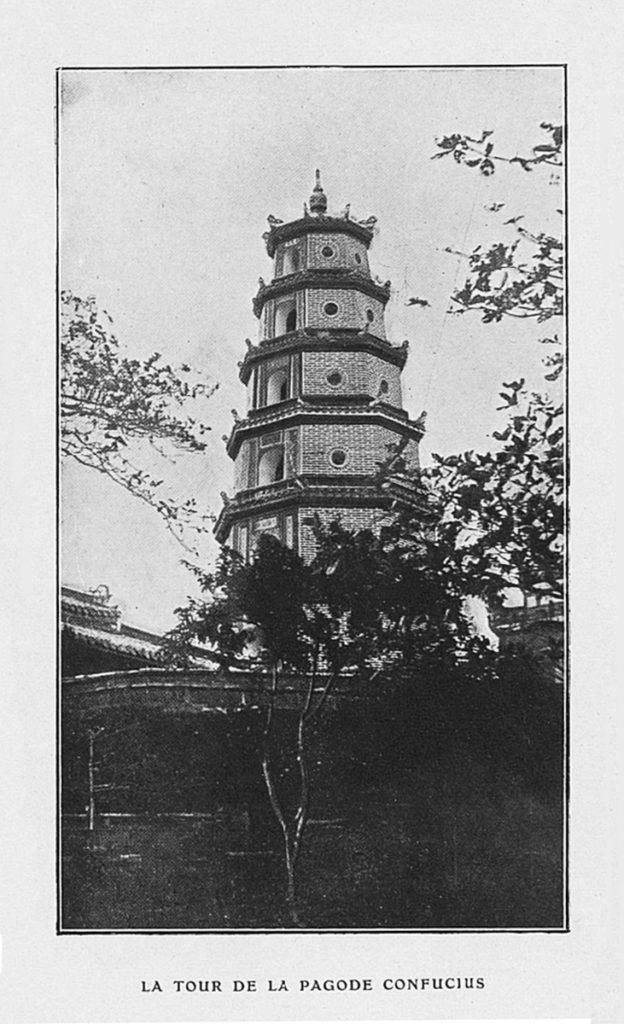

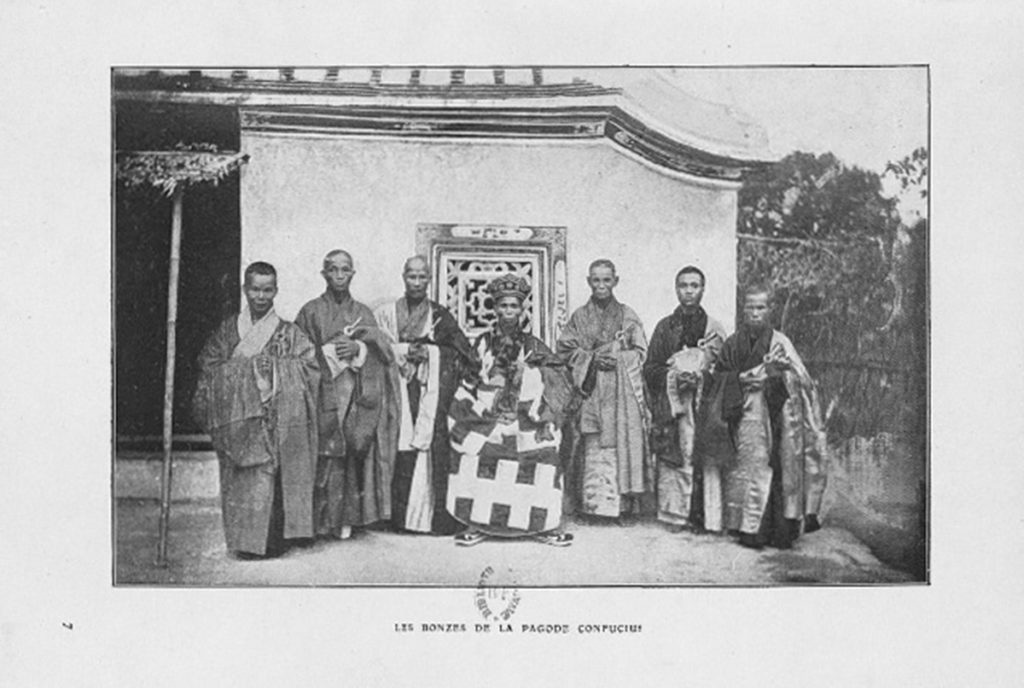

Upstream from the Citadel on the Perfume River, a short distance from the ramparts, a tall, octagonal tower in the Chinese style attracts attention. It functions like a “bell tower” of the great Confucius Pagoda, which serves as the Buddhist cathedral of the capital of the Empire of Annam. It’s in this temple, placed under the invocation of the great philosopher, that all ceremonies of high significance are performed. And in particular, examinations and competitions determining admission to the higher grades of the literary mandarinate.

Not far from the Confucius Pagoda, and still on the left bank, are the Landing Stage and the Baths of the Emperor, in direct and private communication with the Palace by lanes lined with high walls. The young sovereign is passionately fond of steam navigation, and two boats belonging to the Résidence supérieure currently ensure his favourite entertainment. However, it is sometimes necessary to supervise Thanh-Thai’s nautical audacity: one day recently, after commandeering a poor Chinese vessel with a breathless engine, he ventured to cross the sand bar of Lang-Co in an attempt to reach Tourane by sea. This prompted great commotion at the Résidence supérieure, which hurriedly dispatched some qualified officials to bring back the young monarch who had escaped from his capital.

Let’s pass along the right bank of the river.

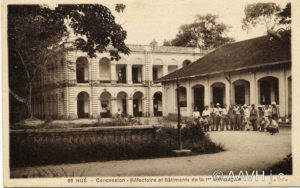

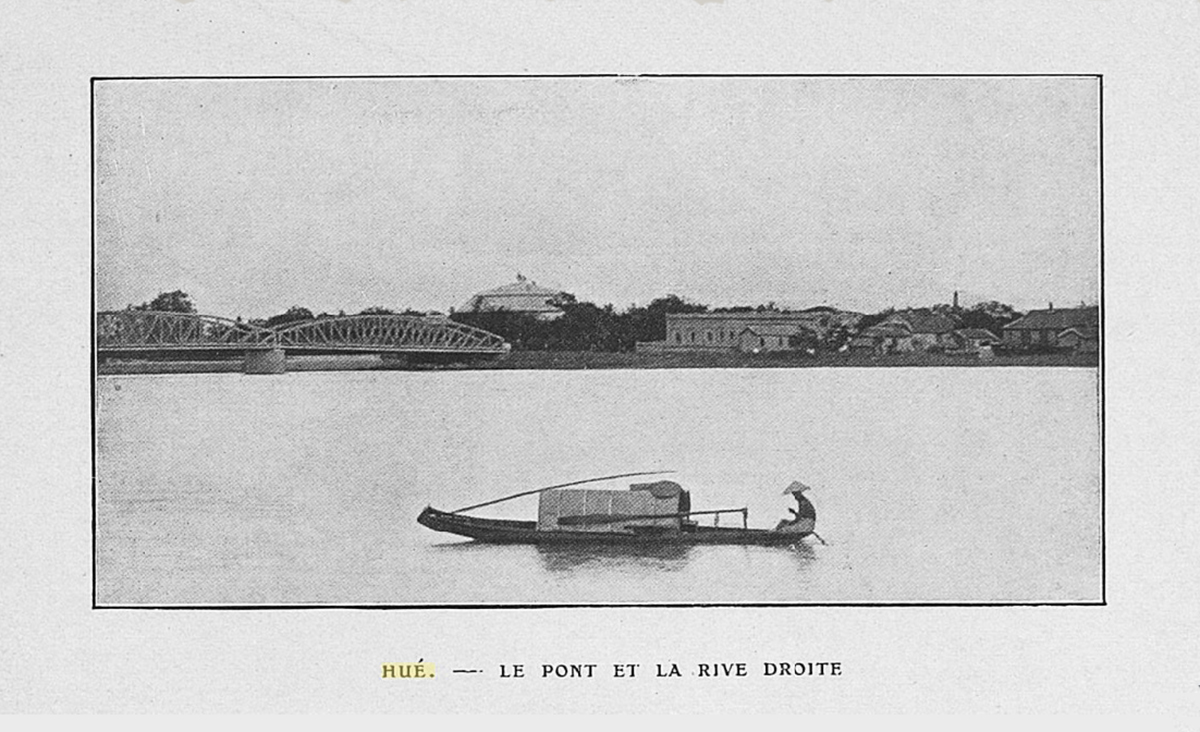

Here, visitors will find a series of modern buildings, mostly official in function, including customs, public works, gendarmerie, treasury and indigenous guard, together with a comfortable and well-kept hostelry. Also located here is the Cercle, where tourists are guaranteed a most cordial welcome. After an exhausting day trip, they will find pleasant pre-dinner relaxation here on the terraces of the club, which overlook the river.

Finally, rising above all these new and constantly rebuilt structures, visitors will see the roofs of the Résidence supérieure emerging from the beautiful gardens which surround it. It is still called, by habit, the Legation, on account of its primitive affectation. It was occupied by our diplomatic agent before the organisation of the Protectorate.

This European quarter, fresh and pleasant in appearance, is surrounded by greenery and forms a strong contrast with the dull, brown half of this composite and imprecise city.

A large iron bridge with its narrow frames, an obvious vanguard of the future railway, connects the two banks and seems to extend a destructive arm towards the old things destined for inevitable disappearance.

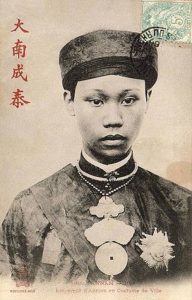

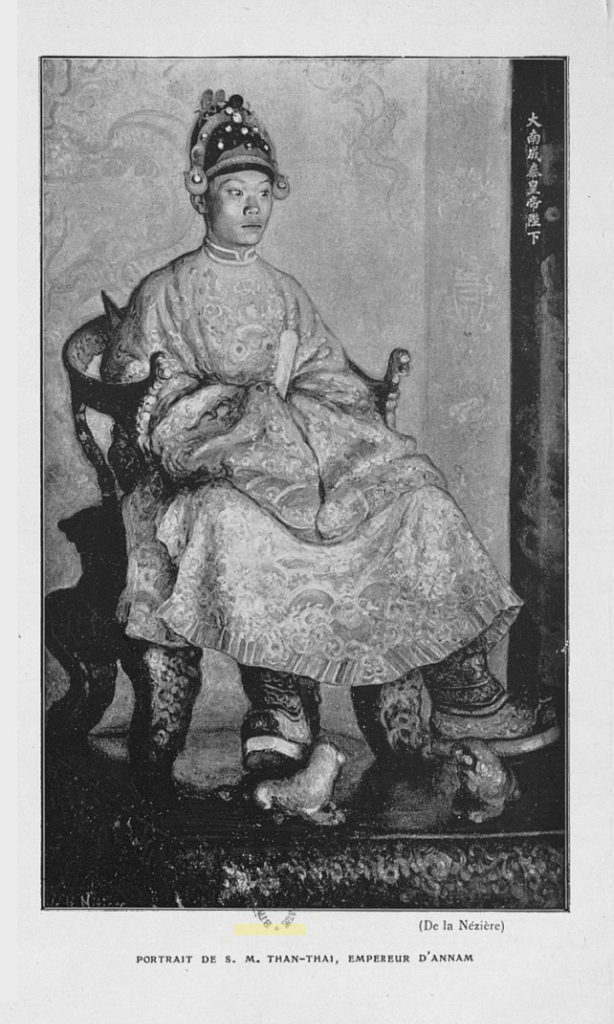

Will Emperor Thanh-Thai be the last monarch of Annam? Let us beware of prophesying in these delicate matters. He is only 23 years old and can therefore live and reign for a long time. But it is to be supposed that this century may see the tricolour flag float over the old ramparts, where the imperial standard, with its sumptuous embroideries and serrations, is now still tolerated. In any case, this absorption will take place without violence: our Indo-China government has too much interest in using to its own end the administrative mechanisms of the old empire. Supervised and framed, the mandarinate forms a valuable tool in the hands of our eclectic and wisely opportunistic administrators.

Indeed, in the skilful evolution towards progress and justice, it is surely better to let the old edifice fall slowly, rather than seeking ingenious ways to effect immediate adaptation. Thus, the evidence of old consecrated skills is still clearly understood and demonstrated here.

A visit to the Citadel, not including the Palace which must be visited separately, occupies a morning.

Here first is the Co-Mat or Council of Ministers, a new construction of modernised Annamite architecture which seems vaguely … seaside-like? Some say that it resembles a casino pavilion on some second-class beach, flamboyantly decorated with dragon motifs. For want of taste, should we think?

The same criticism might well be addressed to the so-called “à la française” décor favoured by His Majesty, which evokes fairly accurately your average “tapestries and furnishings” display in the Maison du Petit Saint-Thomas department store. On the whole, these errors may have their energetic sense: an active policy does not always have time to embarrass itself with aesthetics. In short, this style of decoration is one which befits silky and gilded puppets, all the strings of which are attached to the expert fingers of Monsieur le Résident Supérieur of Annam. Let’s regard it as a brand new “guignol” of a particular kind.

The School of Agriculture, where a fantastic host of orchids prospers and multiplies, forms a group of low and divided buildings, a whole city of greenhouses constructed from light bamboo, with fine lattices replacing windows. And here are the pupils of the course, led by a native professor and duly endorsed by our Agricultural Institute. They go out to the countryside to recognise some species, to analyse some soil. What pain we endured to convince them to cut their long nails curled up into horn clippings! They were much attached to these signs of idleness and patricianism, so incompatible with the handling of the pick and the plough. However, they have obstinately retained their silk robes, their parasols, their fans, their varnished slippers. Thus enrobed, these mandarinal youths file along the narrow paths of the rice field, a hint of disdain on their lips, proud and distant, united, refusing to incline their heads towards the robust soil.

To enjoy the wide-open spaces of the Hue countryside, one leaves the Citadel by the “Bridge of the Assault.” It was amidst great danger, on the night of the 5-6 July 1885, that officers of our garrison of occupation were forced to take this passage after their party at the Legation had been interrupted by an Annamite attack.

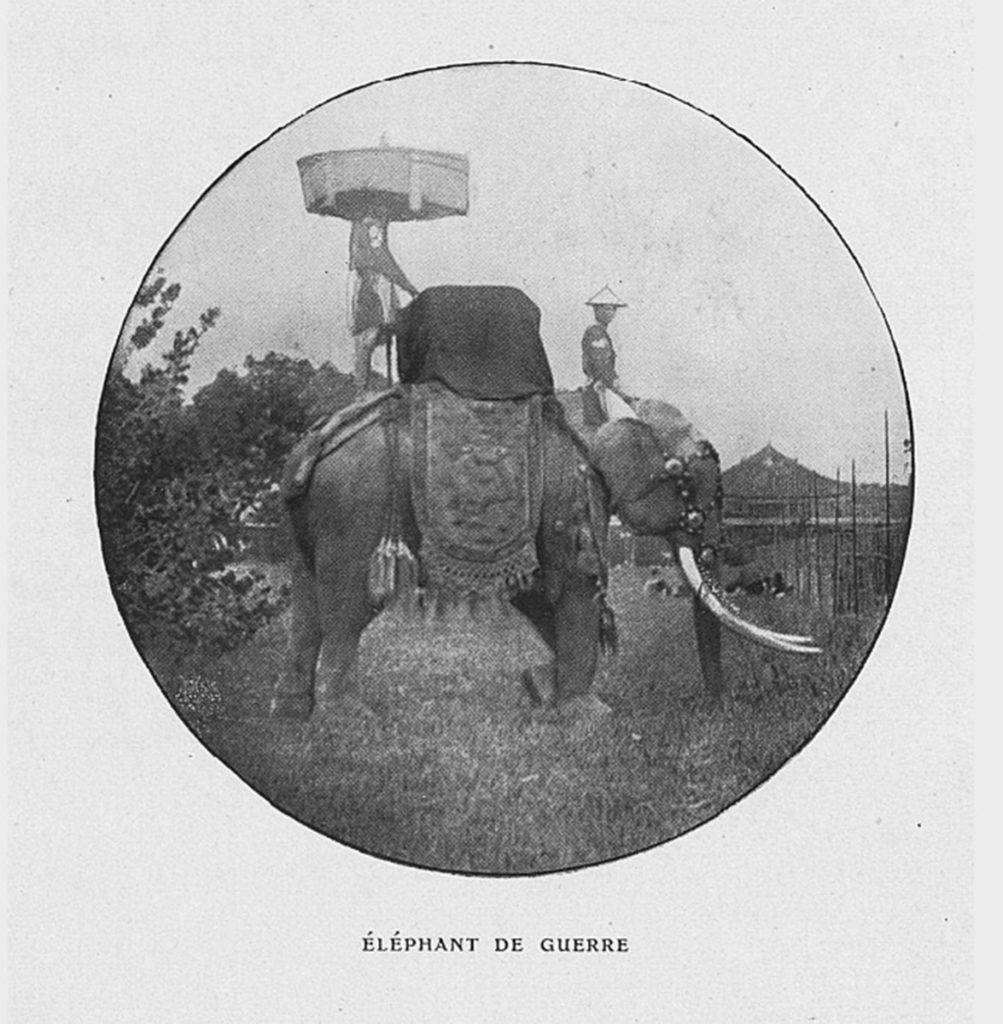

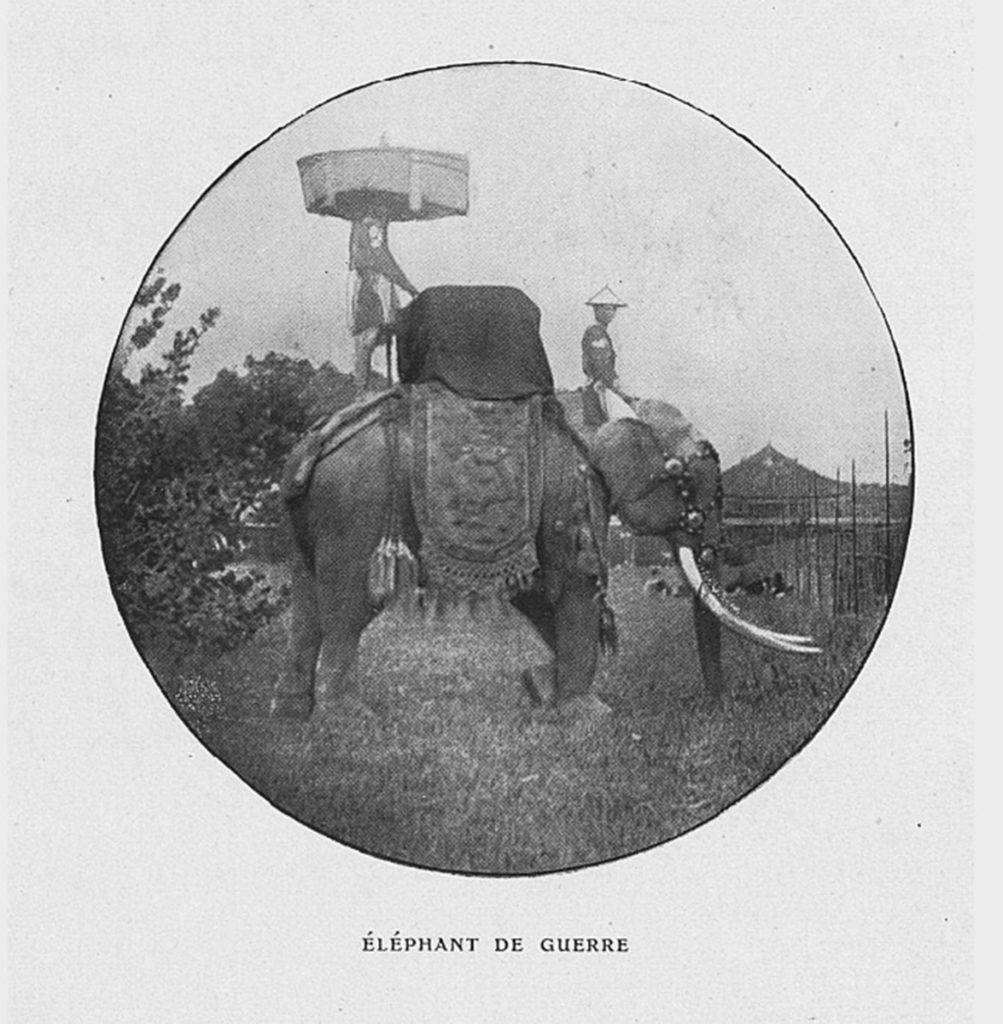

Out in the countryside, one sees His Majesty’s War Elephants returning from their morning walk. Oblivious to the wishes of their mahouts, these heavy intelligent beasts display the malice of a schoolboy, determined to prolong the pleasures of the open air. They tear out clumps of grass, shaking the roots to make the earth fall, blowing on them to chase away the last specks of dust, and finally, swallowing the tasty bites. Their mahouts insist on returning, using their heels and sticks; but the mischievous animals, continuing their meals, shake their big ears and utter fierce cries.

Let’s leave to the tourist-explorer of the native districts the pleasure of discovering the bargains of the trinket: Lots of bric-a-brac stalls where the adventurer may find pieces of beautiful jade, old porcelain or old enamelled copper, all vestiges of rapidly disappearing art industries.

And let’s reserve for the beautiful warm nights of November the experience of attending the Annamite or Chinese theatre, listening to dancers and singers, to orchestras where the tap-luk (zither) and the one-stringed violin draw precious motives, well synthesised by the effeminate suppleness of the Annamite race, with its inconsistent hieraticism, interspersed with playfulness and laughter.

The Palace and Royal Court

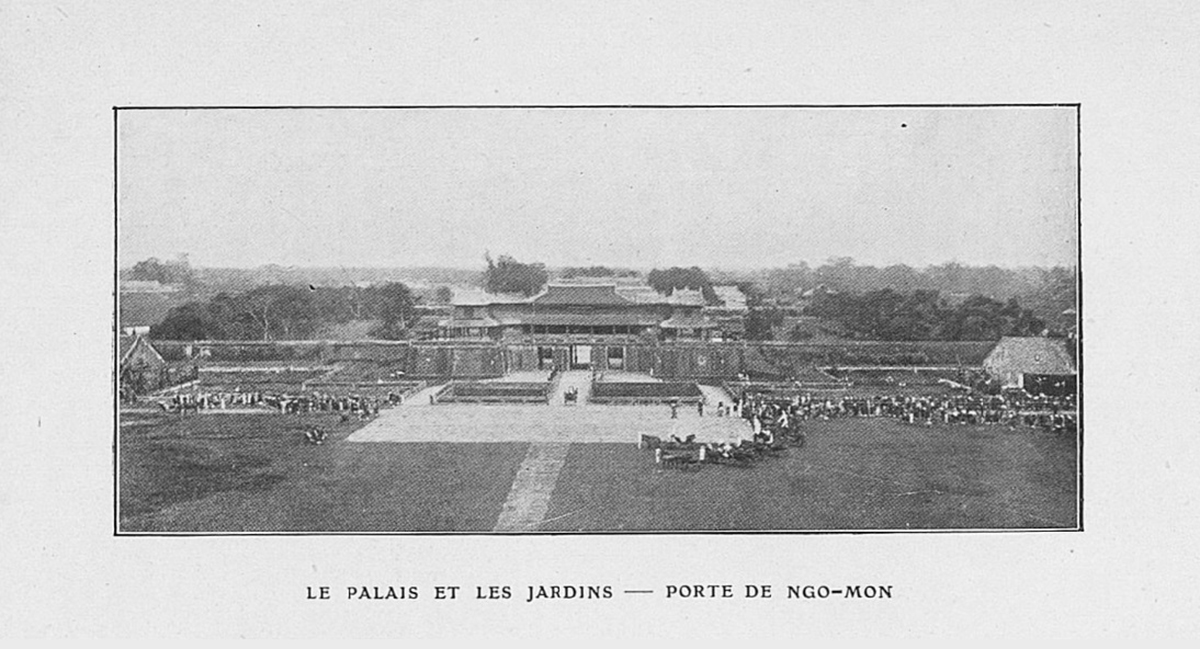

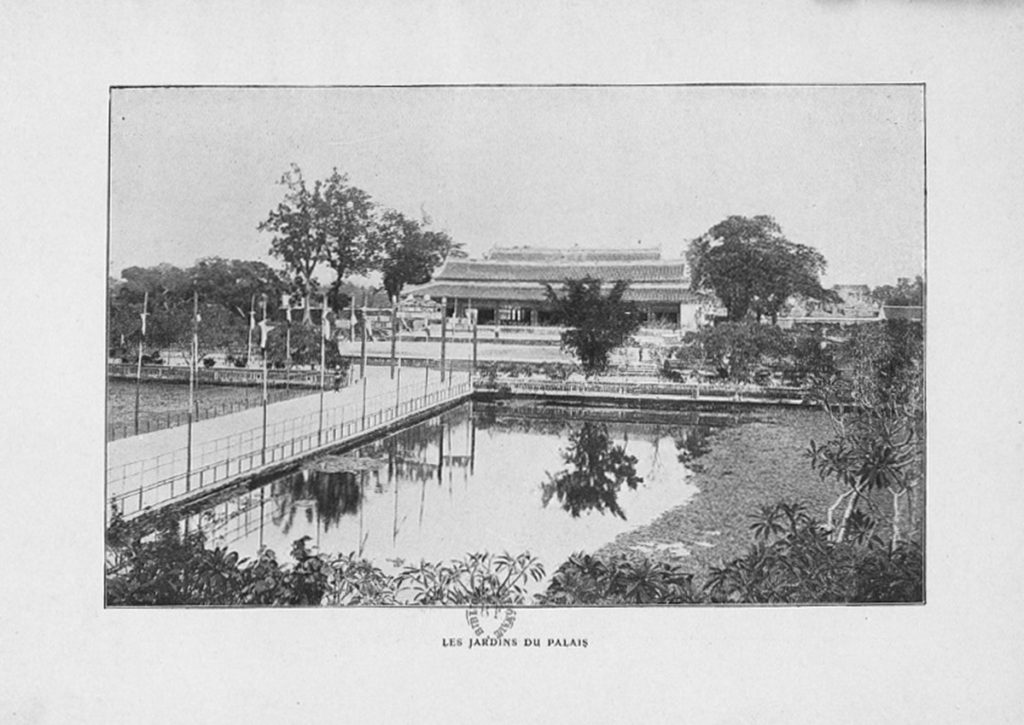

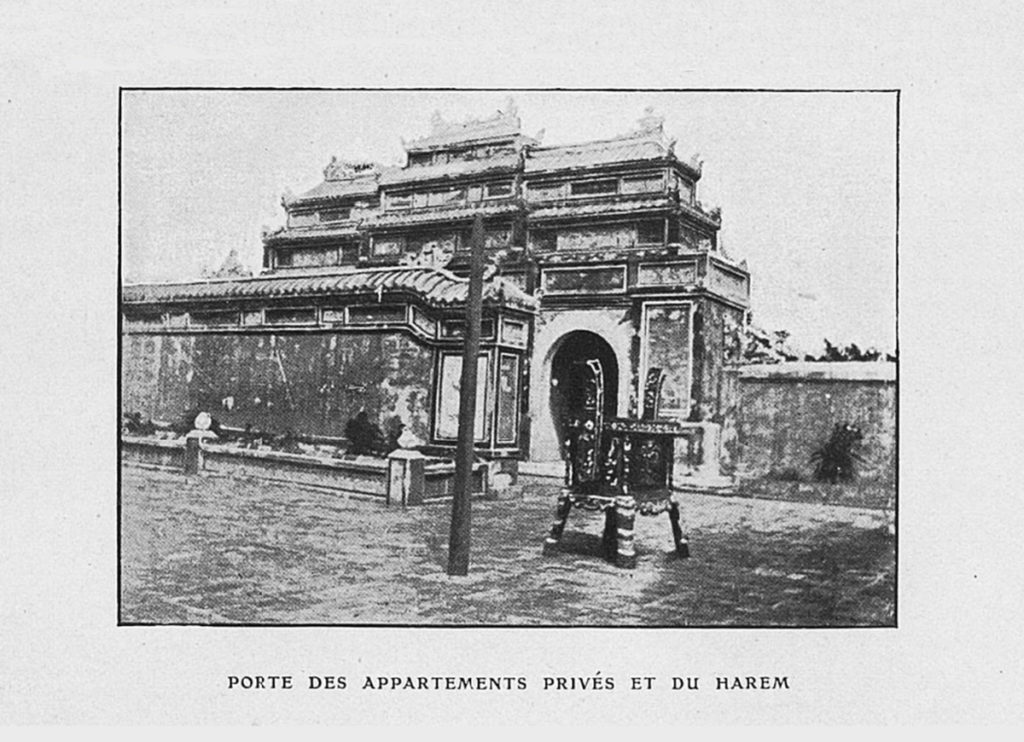

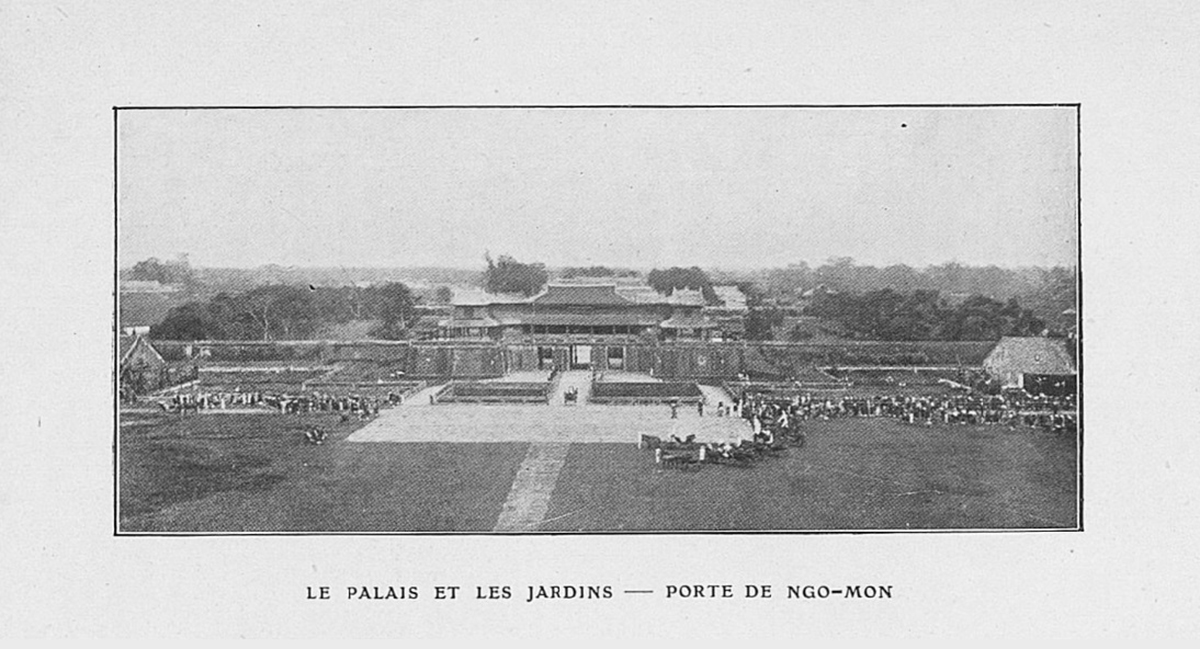

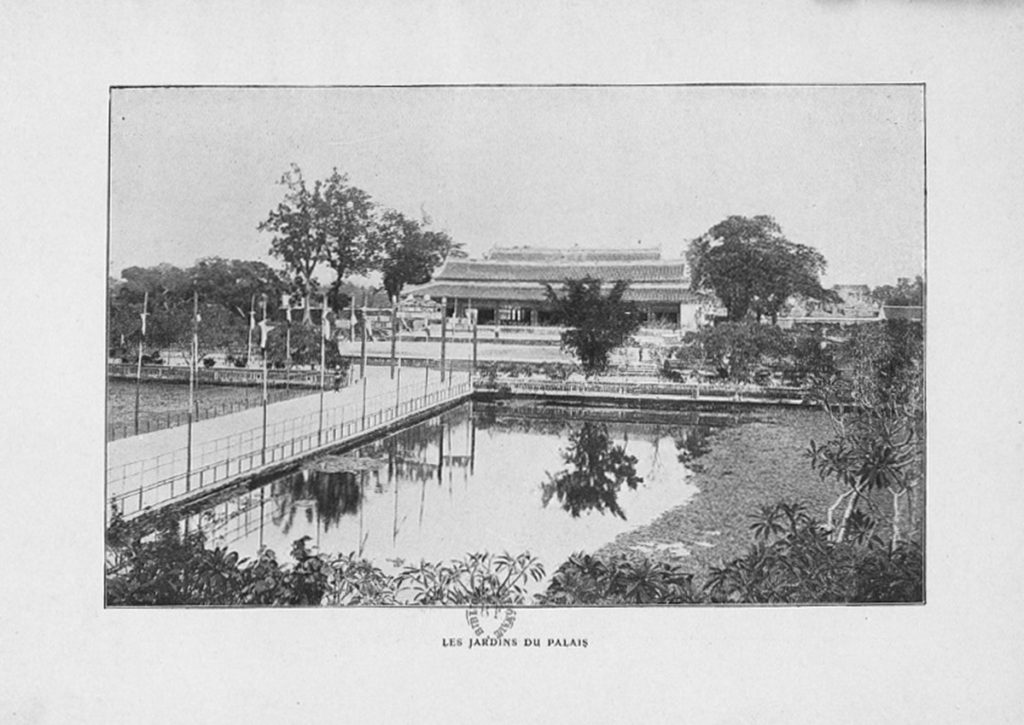

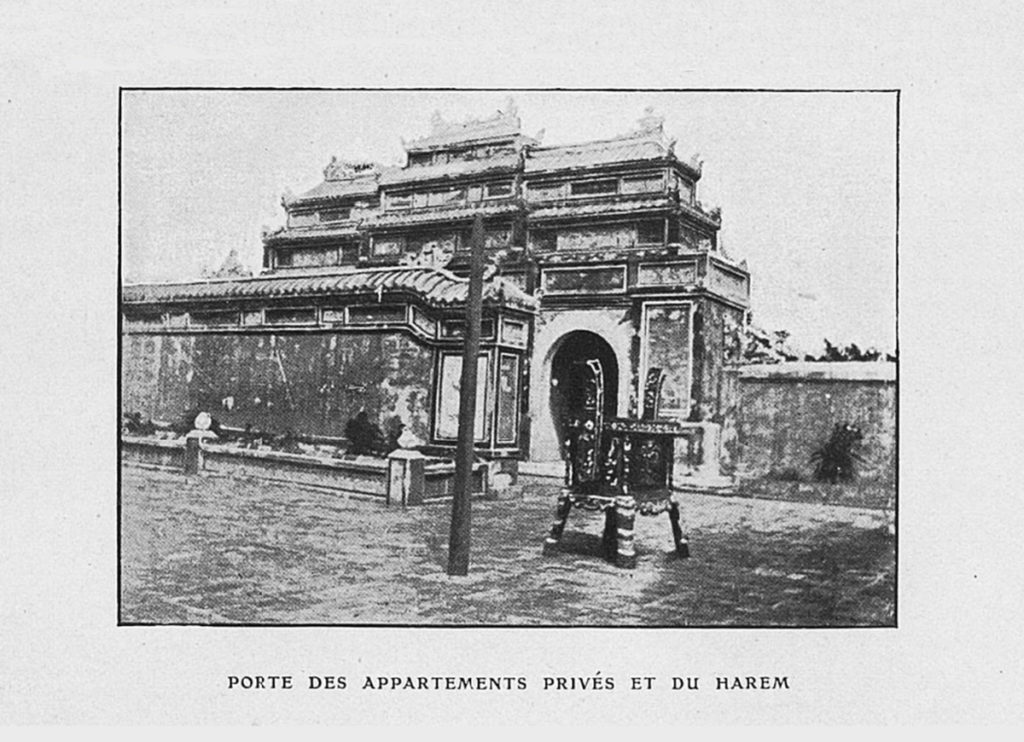

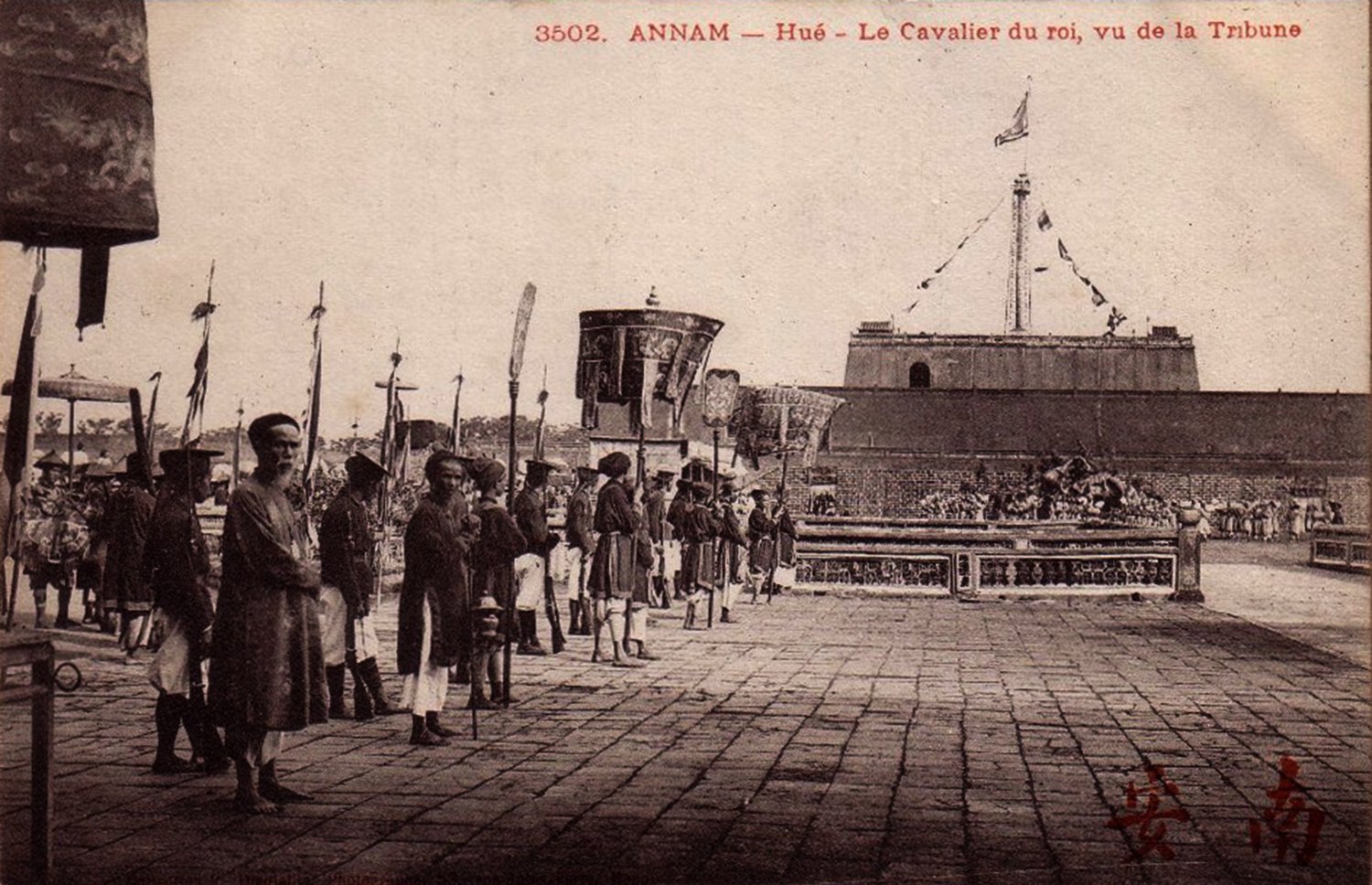

From the top of the “grand cavalier du roi,” a heavy protuberance in the fortified walls, one may obtain an overview of the palace and its gardens. However, curious tourists may see in detail only a very limited portion of this palace and its gardens. The mystery of the royal apartments, the harem and the sacred pagodas is not accessible to anyone.

It was in those hidden places that court intrigues, crimes and revolutions were germinated and played out. And today this is where a young emperor seeks mysterious distractions from the boredom of his idle reign. Sometimes, the echoes of singularly cruel fantasies reach our surprised ears. The sages affirm that it is necessary for us to close our eyes, to leave barbarism in this, its last refuge, which, like the rest, will eventually disappear.

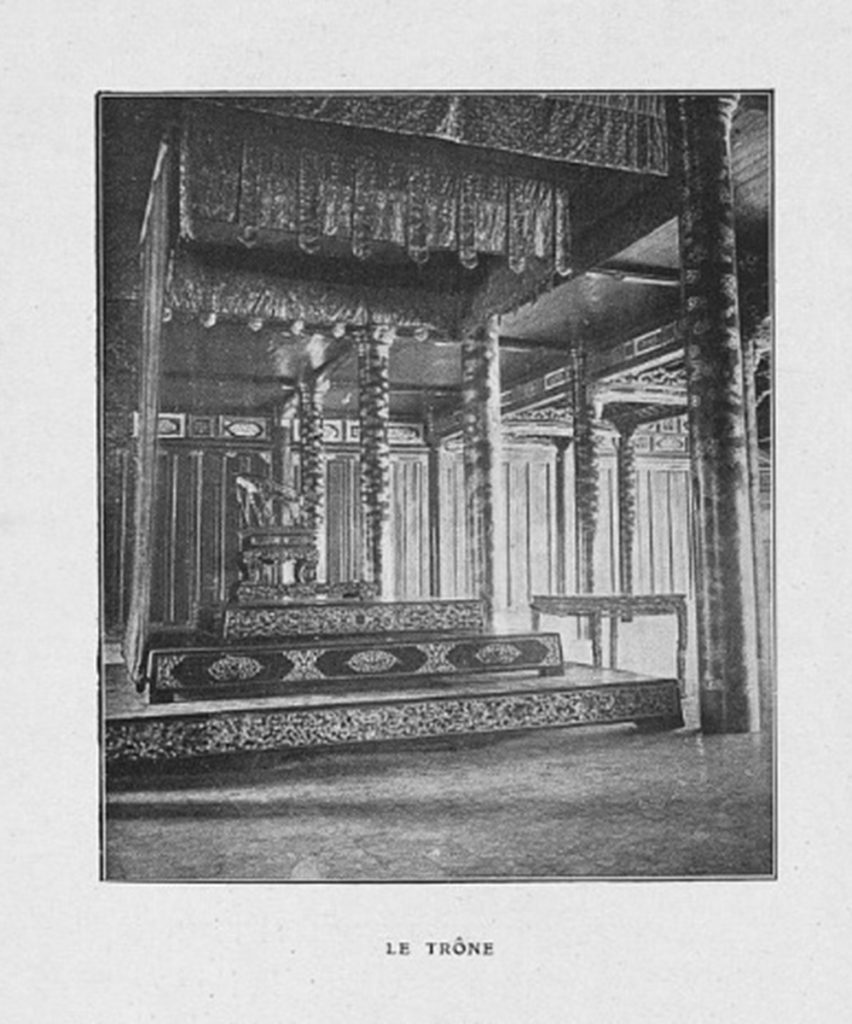

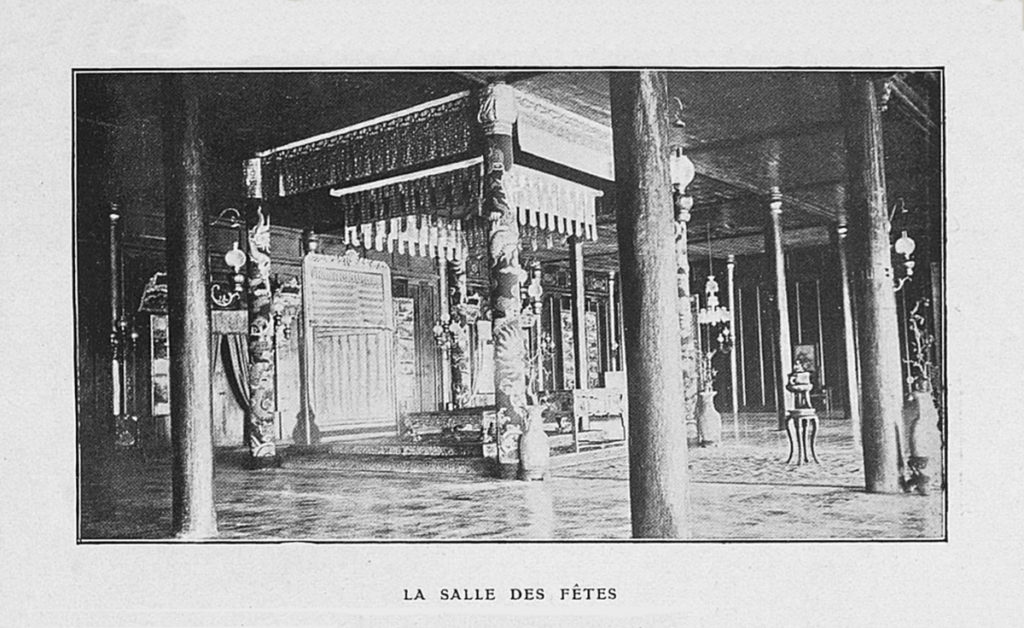

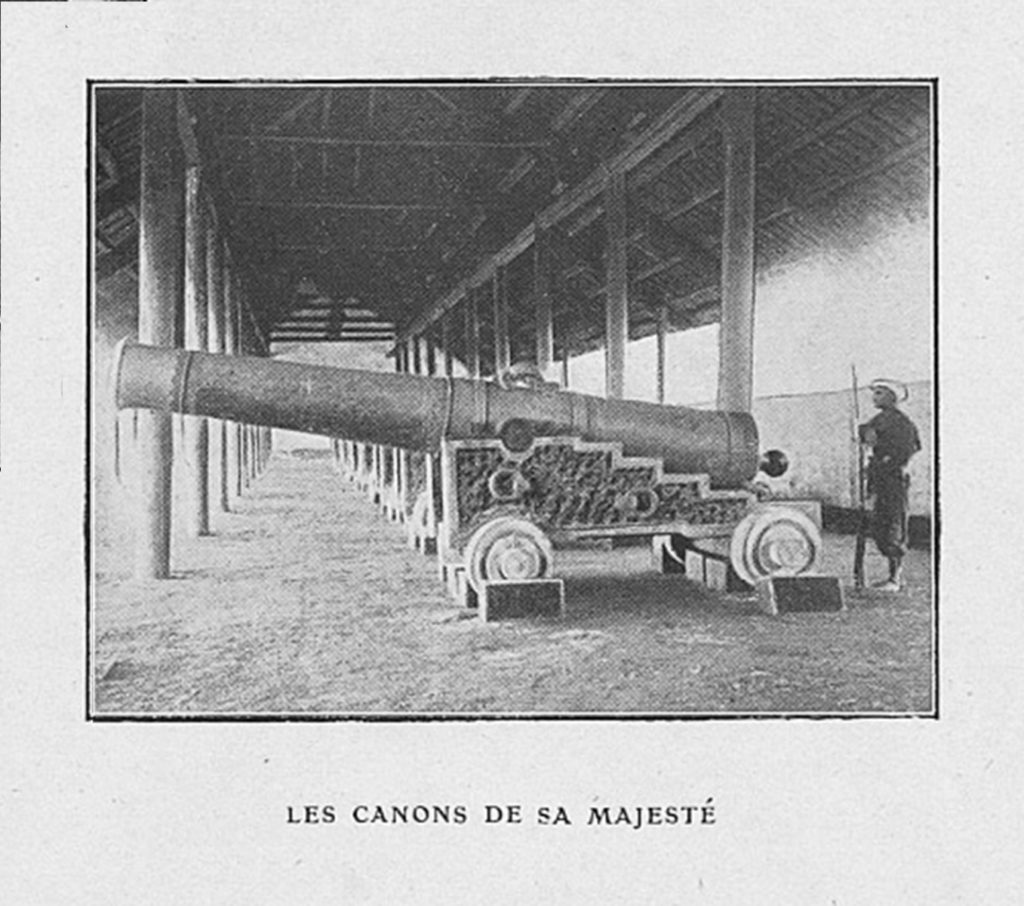

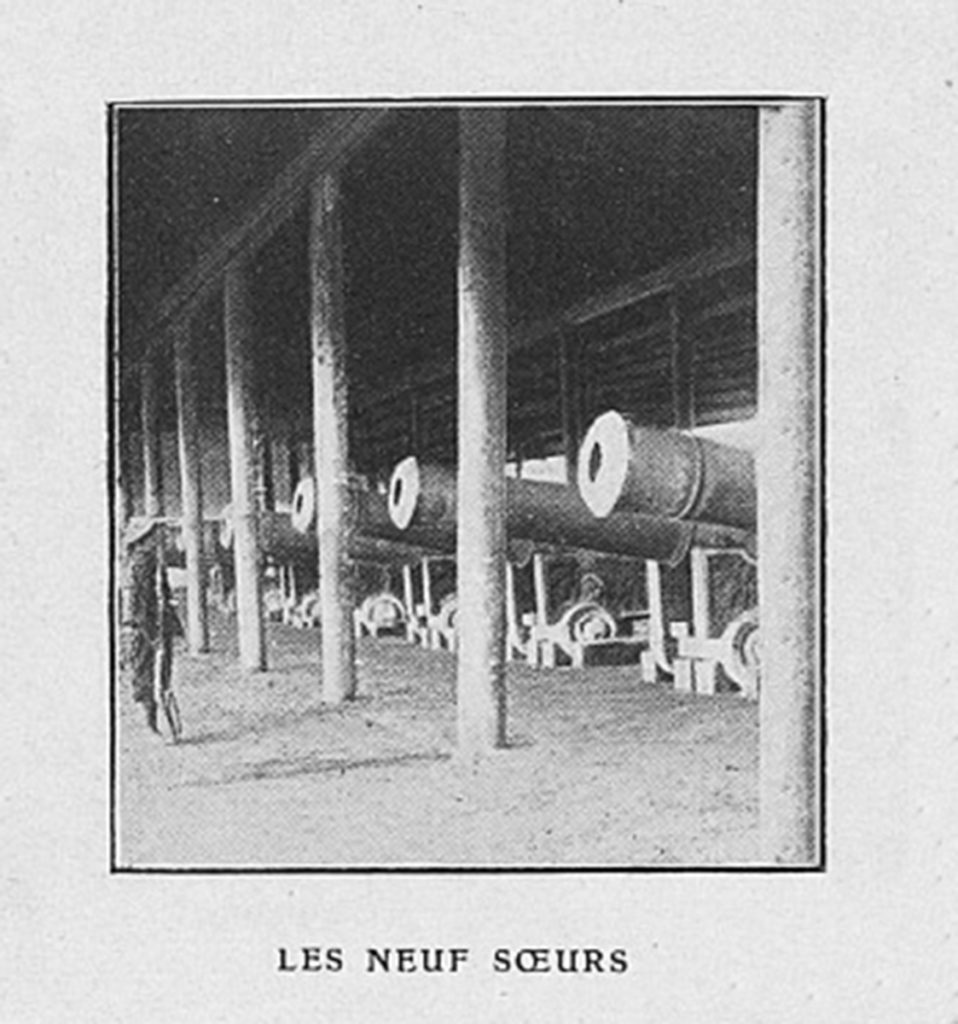

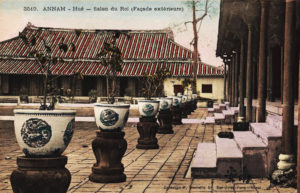

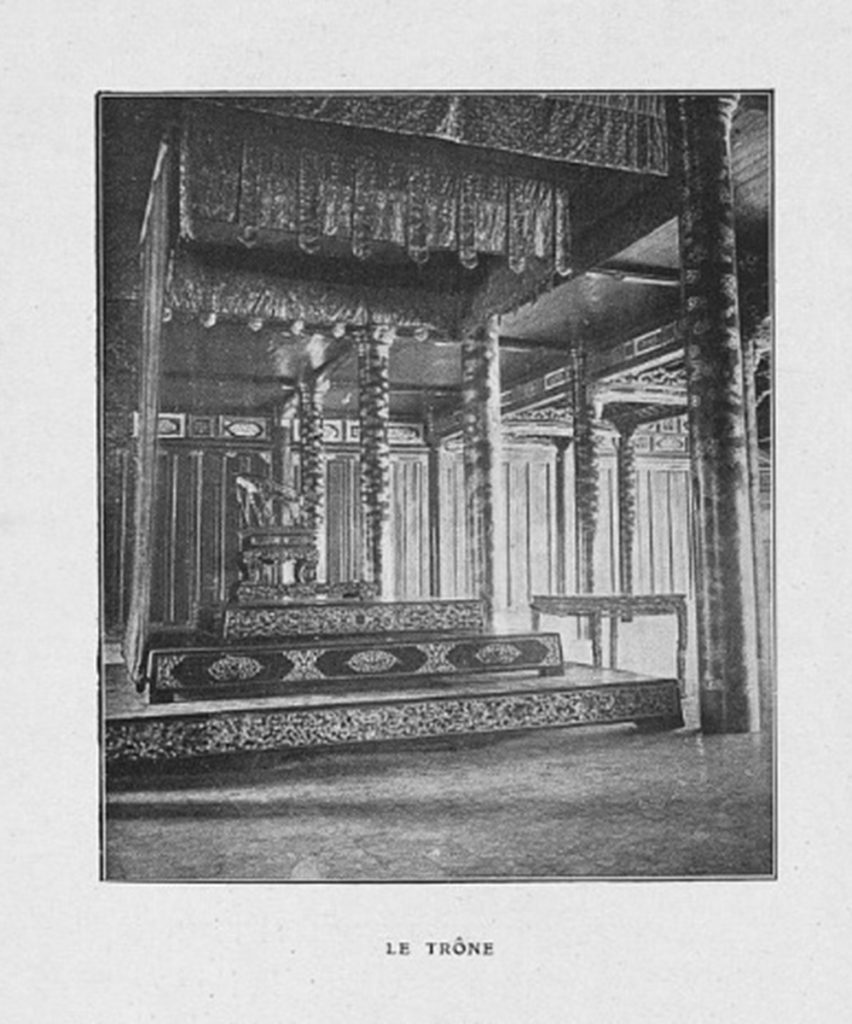

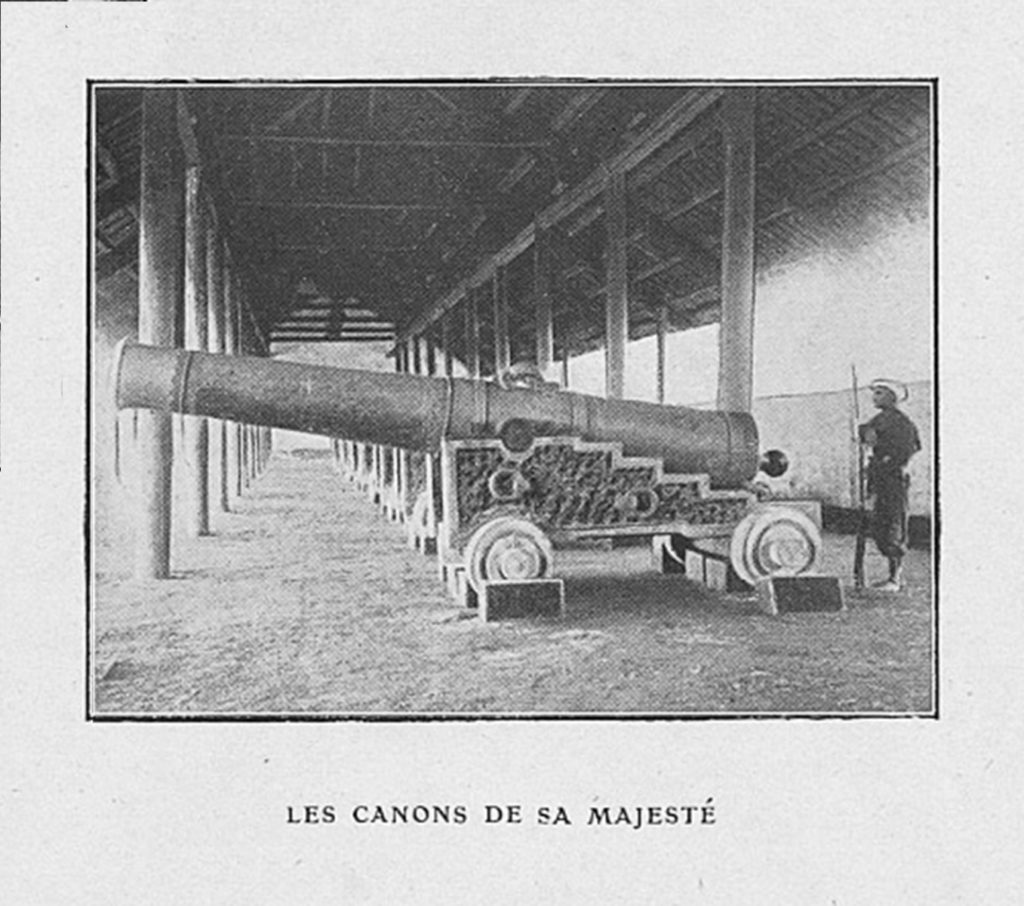

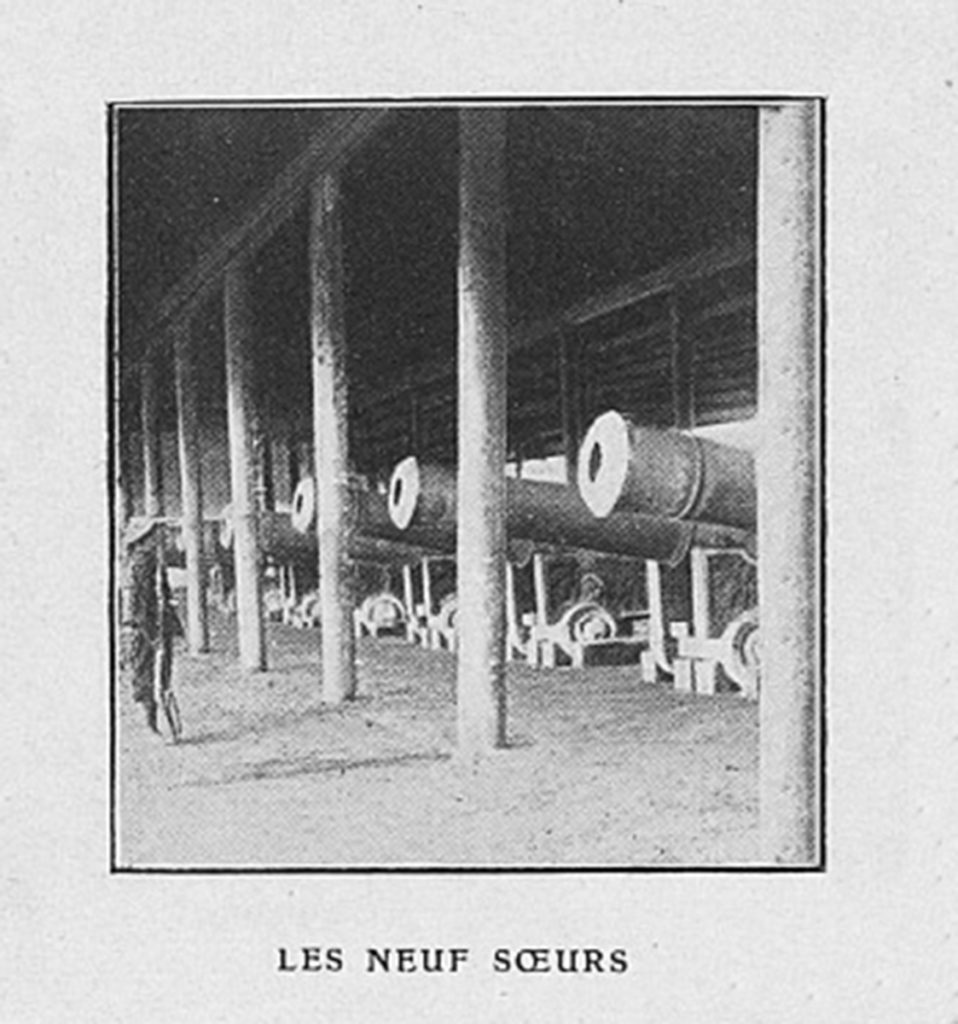

You will then see the throne room, the ceremonial hall, the dining room and the “salon à la française.” You will see the pagoda of the ancestors, the pond with the crocodiles where, until very recently, thousands of young saurians were given as annual symbolic presents to queen mothers. You will see the Ministry of Finance, the bell workshop and the store for theatre accessories and costumes, singularly reminiscent of the rags used by our provincial theatres. It seems that the unique misery and perfume of the chariot of Thespis are the same in whatever latitude! Finally, you will see the “Nine Sisters,” the nine sacred bronze cannon of His Majesty, which now lie silent forever.

One enters the Palace by the great Ngo-Mon gate, which looks out over the “Esplanade du cavalier.” This door is a mass of granite, perforated by vaults, surmounted by tribunes, and crowned with a heavy horned roof. Dragons, clouds, bats, sacred books, brushes, tap-luks (zithers) and fans, motifs of architectural ornamentation, are reproduced and multiply on columns, on carved beams, on coffered ceilings, at the corners of roof ridges. With an intelligent guide, an interpreter or a scholar from the Résidence, it’s possible quickly to enumerate these few symbols which reappear everywhere in Hue, representing the sum total of the artistic imagination contained in sculptures, enamels, woodwork, balustrades and terraces, as well as in a more delicate range of knick-knacks, incense burners, teapots, cups, trays and boxes.

However you view it, Annamite art has comparatively few strings to its bow, just like Annamite music and dance, which revolves around the repetition of a few monotonous and restricted motifs. It is by its assembly and the association of the monument with nature that the Annamite people take interesting revenge. It certainly has a sense of “décor,” but we must not look too closely. The artifice is often coarse and fragile, of a kind analogous to that abundance of votive offerings in gilded and coloured cardboard which one finds in Taoist worship.

At the corners of the pagoda roofs you’ll see figures of monsters, with gaping mouths and menacing tongues. From a distance, the subjects seem to be treated in mosaic, or at least in vigorous ceramic work. They stand out strongly against the dark foliage of the great pines.

Yet as one approaches, one discerns a frightful polychromic conglomerate made from the debris of old cups and plates, glued onto poor mortar that’s softened by the tiniest drop of rain. In this way the monster, an ephemeral architectural motif, loses, one by one, its claws and its scales.

After passing through the vaults of the Ngo-Mon gate, you come to gardens with water features. Here one enters a wide stone passageway, framed by two arches with bronze columns engraved with the legendary dragon, which support enamel panels inscribed with mottos in Chinese characters, similar to those found everywhere in the Palace, as well as in the Tombs scattered throughout the graceful countryside of Hue.

These characters mean, in turn:

Righteousness, integrity, justice.

Greatness, eternity, longevity.

Direct path to radiant virtue

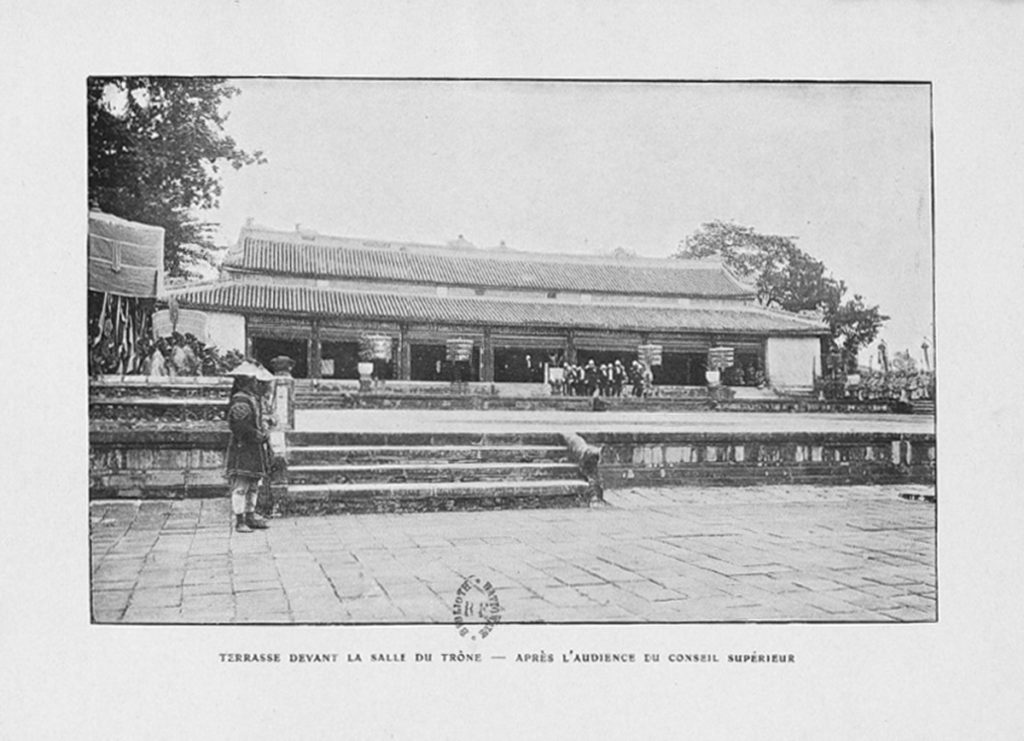

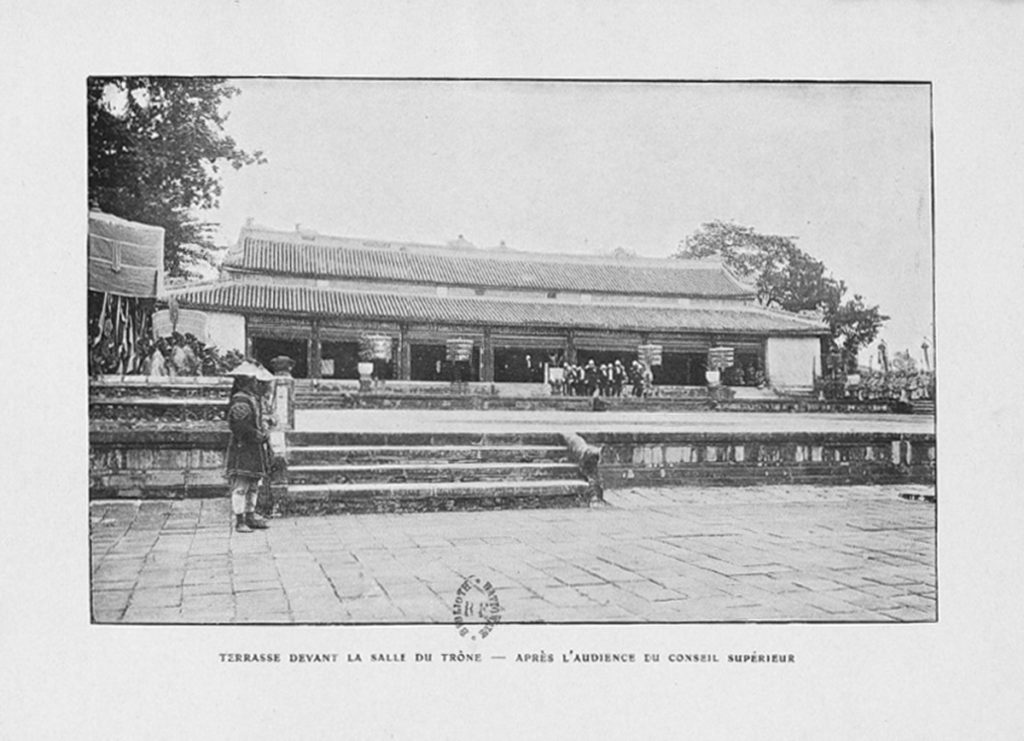

Let’s continue to the terrace of honour, which provides access to the Throne Room. When the monarch received the Conseil Supérieur last year, this terrace was animated with a display of banners, a flickering of sumptuous gilded silk robes, while, on the right and left, on large grassy areas, the War Elephants, then in high formal dress, swung their trunks solemnly, like monstrances.

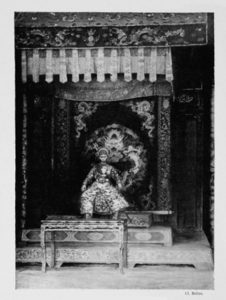

The official reception in the throne room was a remarkable spectacle: the hieraticism of the little emperor, encamped very high, as if on the summit of some dazzling rockery, enveloped in his regalia of gold, silk and precious stones; the marble immobility of the mandarins, bearers of insignia, eunuchs and guards distributed all around the throne, their eyes fixed obstinately on their jade horns, that indispensable accessory of the great outfit, in order to ensure the dignity of the eye by preserving it from uncertainties.

This strange and grandiose spectacle, descended from the depths of the ages and faithfully perpetuated, left the average western viewer adrift on a vast sea of enigmas.

The speech of the governor, the reply of the king, translated by the great interpreter, offered nothing unexpected. After individual presentations, a glass of champagne brought this ceremony to a close after less than one hour.

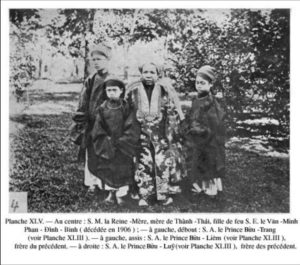

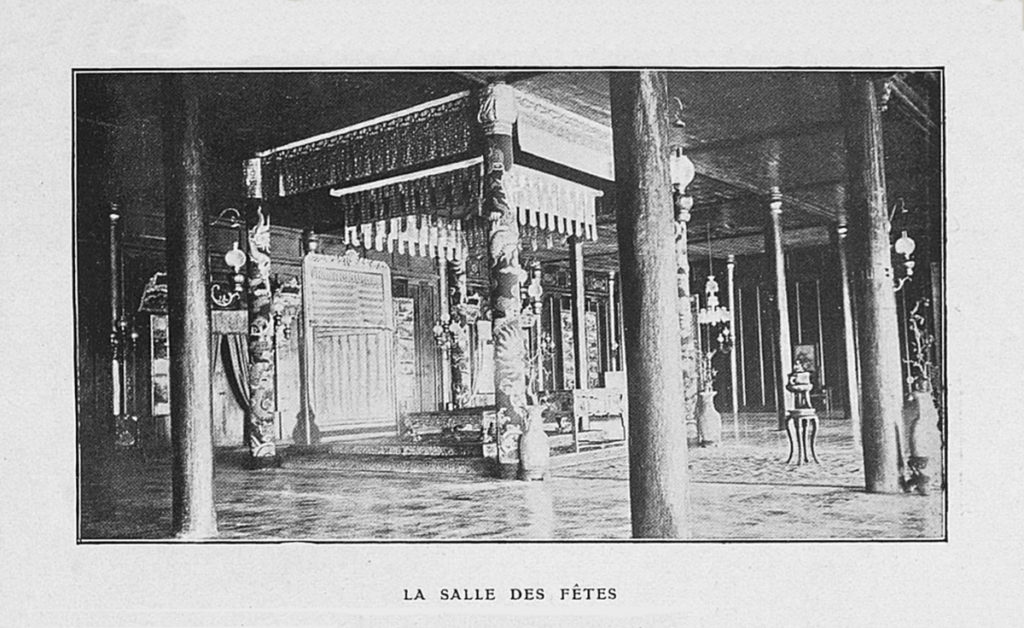

Longer, and much more entertaining, was the gala evening at the Palace. Here, it was not impossible even for a secondary personage to make contact with the young princes, brothers of the king. These elegant adonises sported chignons and were dressed in marvellous silks, from which emerged only the finest extremities. These young princes have renounced betel and may add an ivory smile to the natural charm of their figures. The emperor himself, in contrast, remains reactionary on this point, revealing at moments of friendliness a tooth of ebony. All of them are quickly conquered with talk of the bicycle, their dominant passion. And they are particularly moved and ardently attentive when engaged in conversation about the possibilities of modern steam power – “Horseless carriages can now travel as fast as steamboats…. That’s very fast!”

During these elementary insights into technological progress and sports, classical singers unfolded their monotonous and melancholic poems, developing their reptilian gestures, parallel, slow and supple, in the attenuated light, which gave their tawny arms the shade of brownish gold.

A young and very obliging clerk of our Résidence, very initiated to the rites, has been assigned to the Ministry of Finance. It would be imprudent, perhaps, to leave the vault with its piastres and bars of gold without control and without a European guard. This ministry is in fact more of a depository, a store for precious goods. In its halls there reigns an absolute peace, quite a contrast to the rumours and intrigues found in other royal bureaucratic hives. Preserved here are precious things used for the making of royal costumes, collections of earthenware for the current needs of the palace, large bolts of saffron-coloured paper and gold spangles. This is where the official records of scholars and royal delegations are written. The ministry also preserves the insignia of the mandarinate of the various classes, which are distributed gratuitously during promotions; And, lastly, a real oddity… abundant supplies of cinnamon, of very superior and very expensive quality, a condiment of constant use in the imperial kitchen!

And here, set apart, is the emperor’s special casket, which contains over 60,000 piastres in old money. This hoard was constituted following excavations carried out beneath the old mandarin dwellings of the Citadel, destroyed following the proscription of their once powerful mandarin owners who had unwisely become the focus of ambition and intrigue.

We should add a little about royal finances. Visitors may be curious to know what the part is represented in the great budget of Indo-China by the court of Annam, its high dignitaries and the many royal officials of all kinds. Here are exact figures from the last budget agreed by the Conseil supérieur of the colony.

The government general of Indo-China grants the Annamite government an annual sum of 960,000 piastres, or 2,400,000 francs. Of this sum, the court receives 280,000 piastres, or 700,000 francs. Of this endowment, until recent years 25,000 piastres or 62,500 francs were spent on the three queen mothers, surviving wives of deceased emperors. Lastly, the expenses of the king’s pleasures and his table are ensured by a monthly payment of 4,000 piastres or 10,000 francs…. That’s 120,000 francs a year spent on the young emperor!

It is difficult to explain this last sum, in a residence entirely lacking in night-time restaurants, betting shops and opera houses; And since the constitution encloses the Emperor in his palace and tolerates only short walks by him outside its walls, one understands still less the size of the subsidy. On the other hand, if the purse of the royal pleasures seems overly provided, the total budget which ensures the salaries of the numerous indigenous officials of all classes, spread over the whole territory of Annam, seems very modest: just 680,000 piastres, or 1,700,000 francs!

It is customary to repeat that, if mandarins and the mandarinate apparatus are paid little, they know how to make complementary resources; and that there would be no advantage in paying them more, since they are able to conceal the misappropriation of public funds very easily. However, this singular reasoning, adapted specially to the ancient customs of Asia, loses its value every day. These days, the indigenous official, caught between close French administrative supervision and the easy slander of his citizens, can no longer realise the fat prebends of former times.

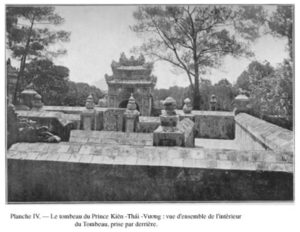

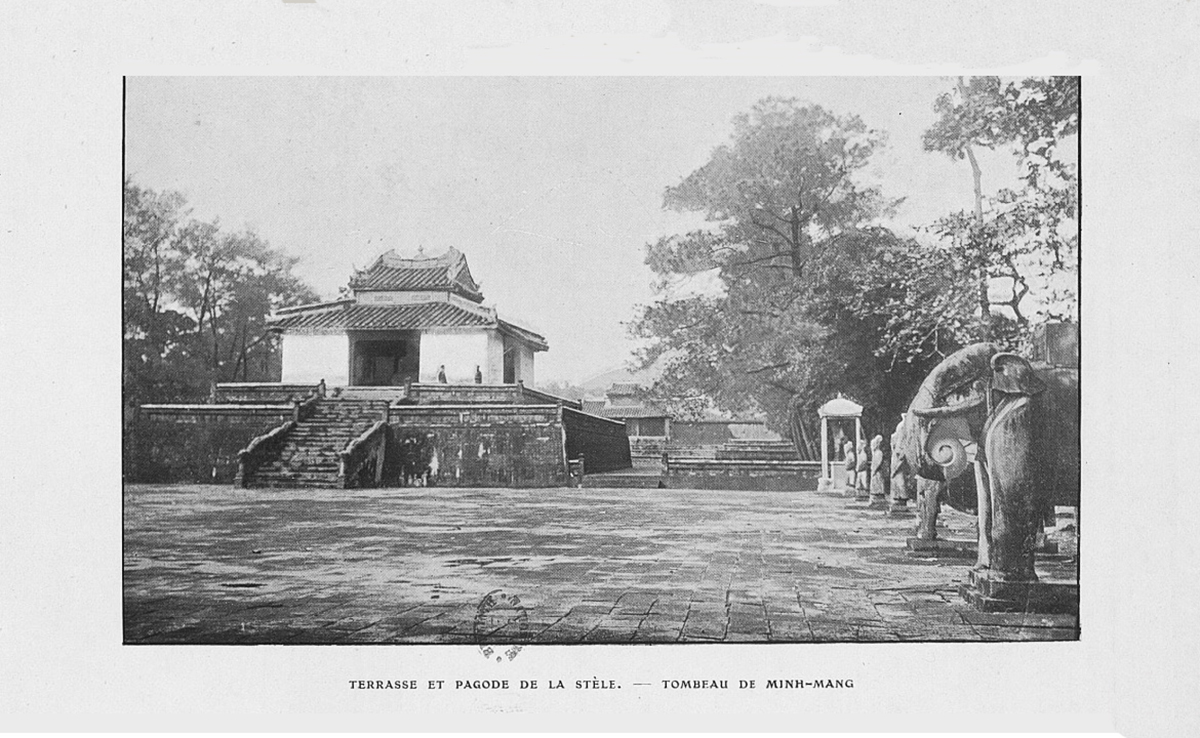

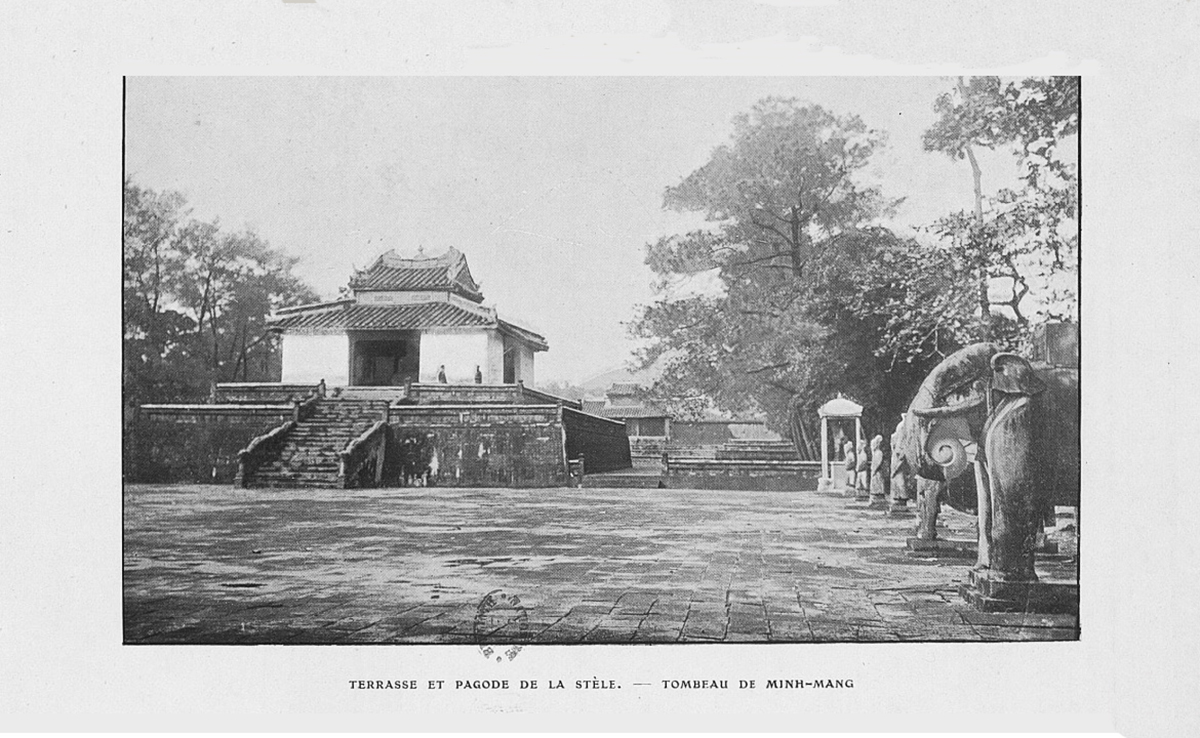

The Tombs

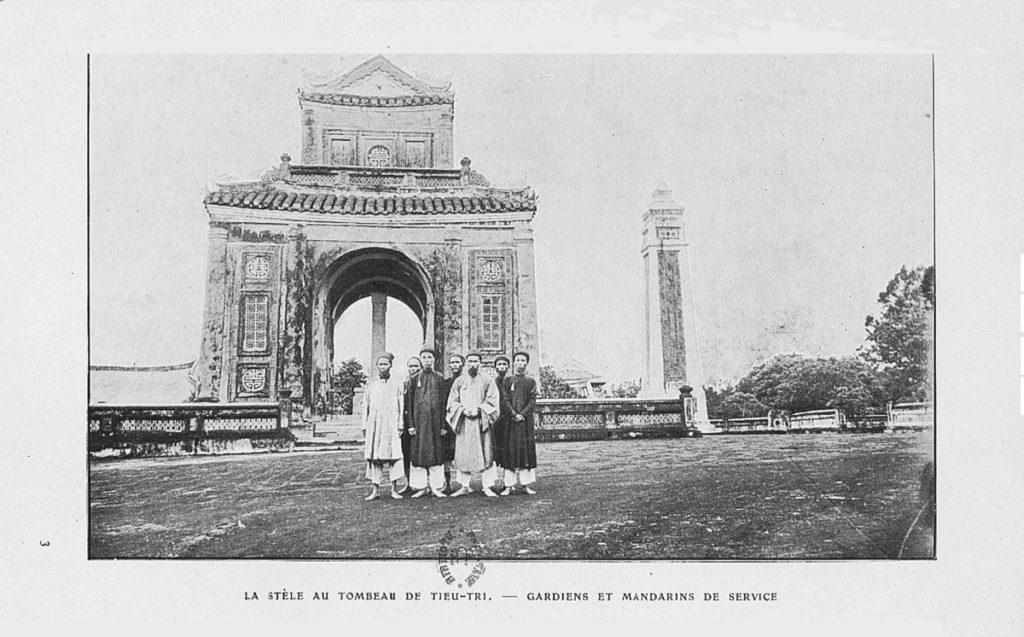

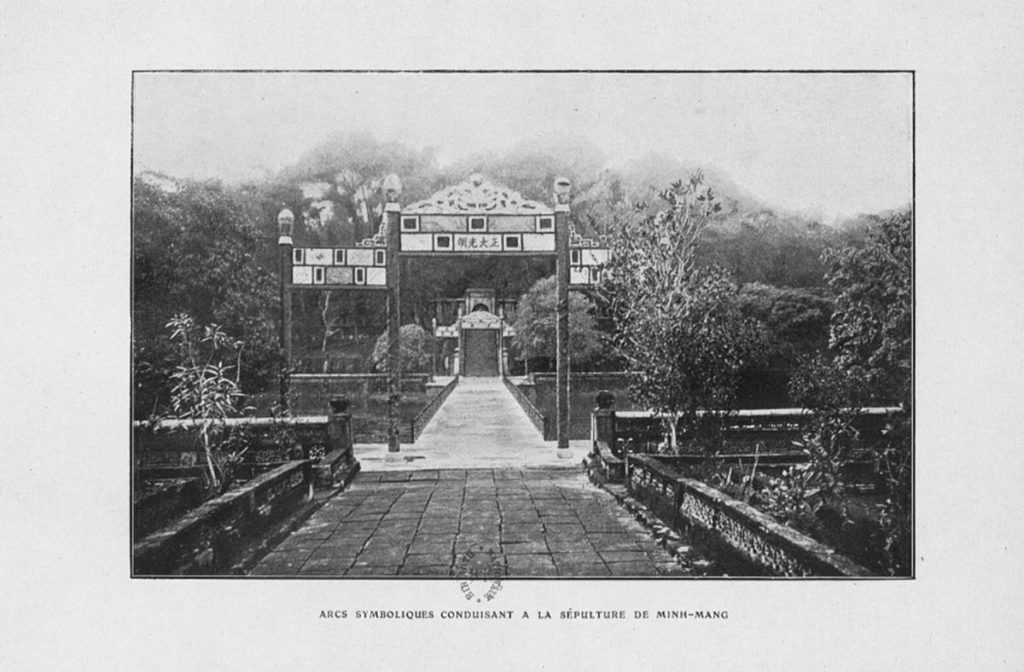

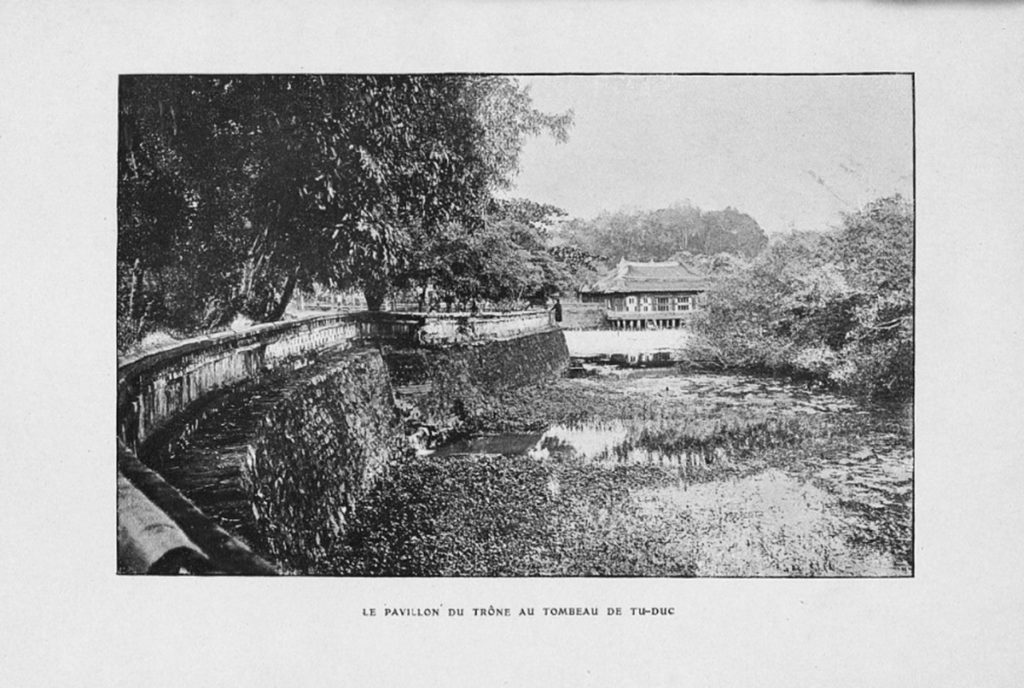

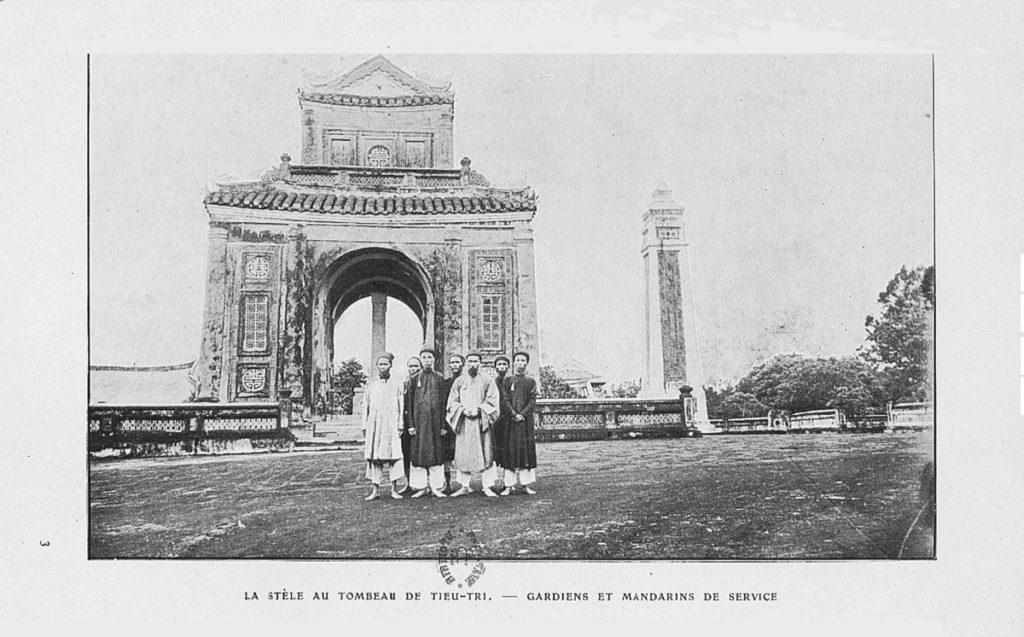

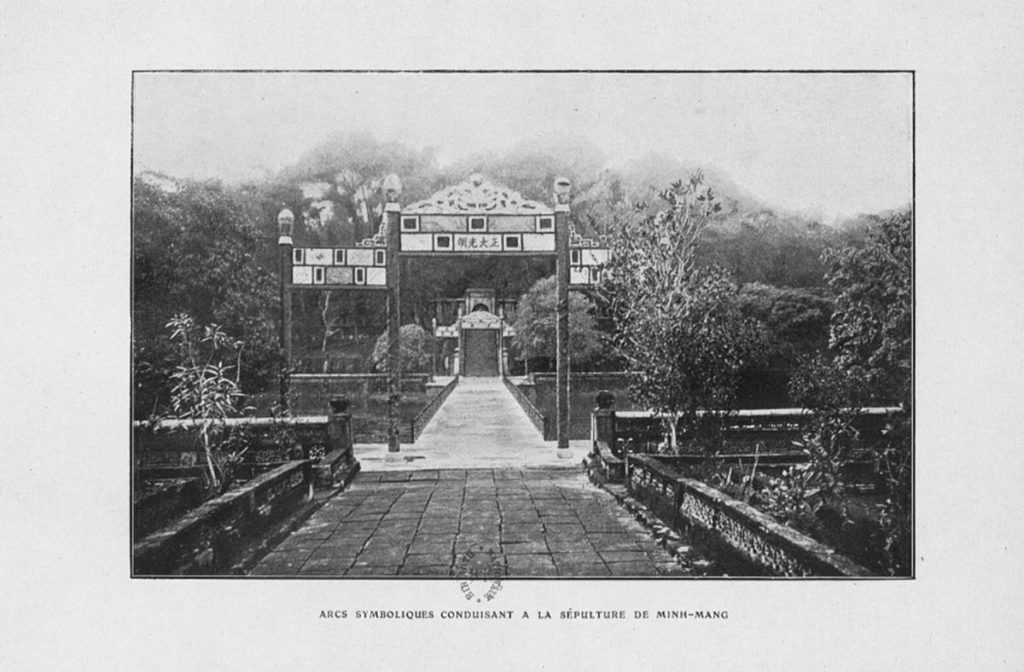

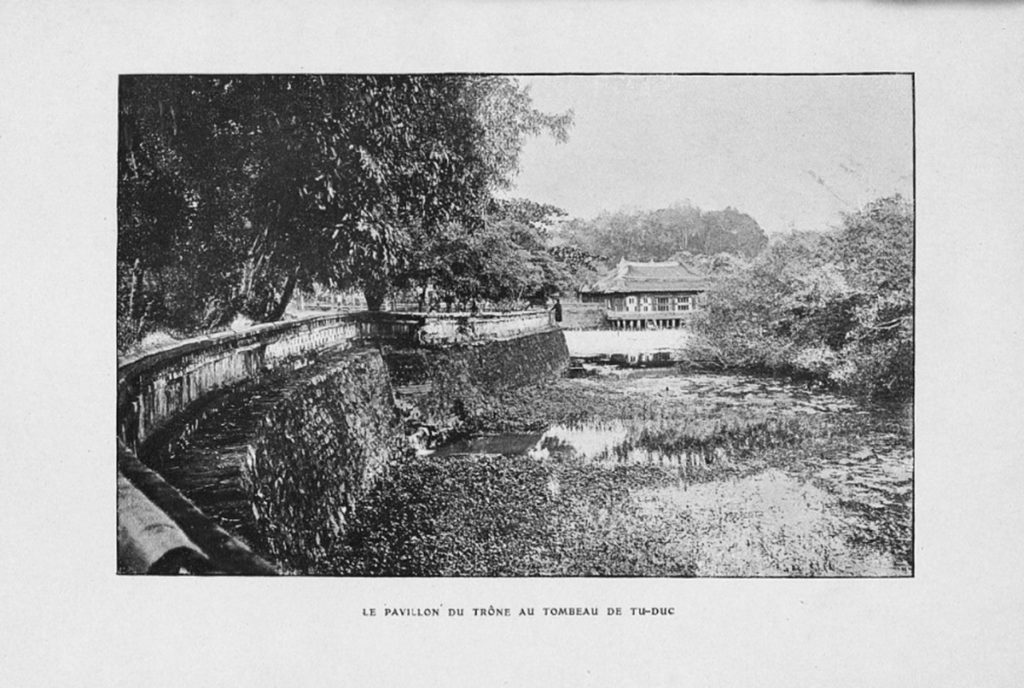

The main interest of an excursion to Hue focuses on the tombs of the emperors. The oldest of these tombs date back less than a century. For the older dynasties prior to that of the last six emperors, one searches vainly to find necrological traces, even ruins, left on the ground. There is a mystery here. It seems that this architectural piety, symbolic and decorative, emerged spontaneously from a sort of renaissance in which we may have played, perhaps in a small way, the role of the Italians. The age of the Citadel was also marked by the creation of grand necropolises built amidst ornamental lakes, all built to a royal design based on that of the Gia-Long Tomb, the oldest and wildest of the classical tomb quartet which the tourist should not omit to visit: Gia-Long, Minh-Mang, Thieu-Tri and Tu-Duc. When one considers the elegance of their avenues, the Versailles-like width of the stone steps which give access to their terraces, the layout of the balustrades, one wonders if the same French officers who built the dark ramparts of the fortress did not also give indications of aesthetics for the mausoleums?

In any case, a real harmony emerges from these constructions, situated in the grandiose settings of hills planted with maritime pines and giant ficus.

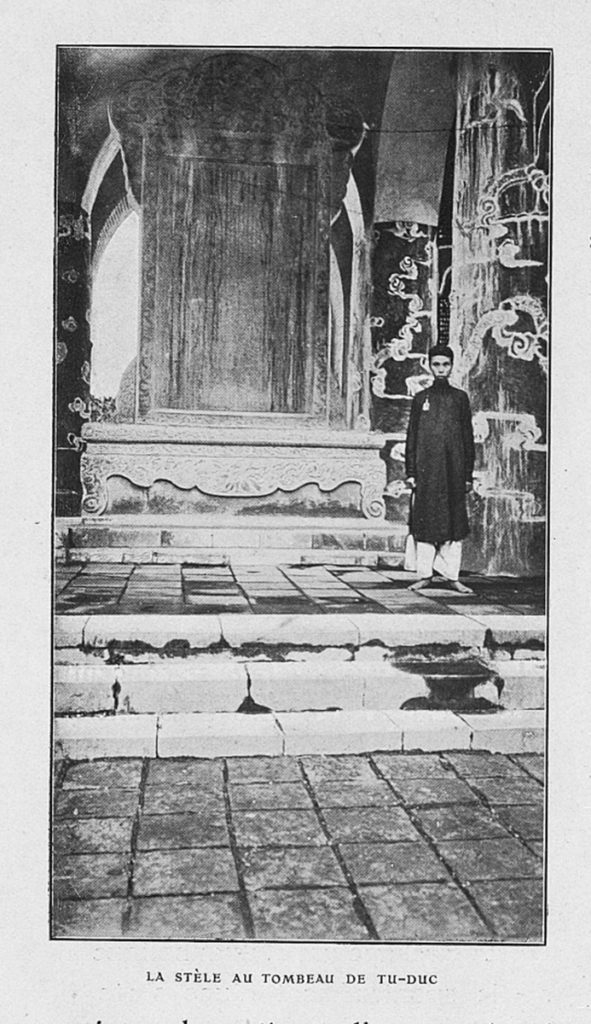

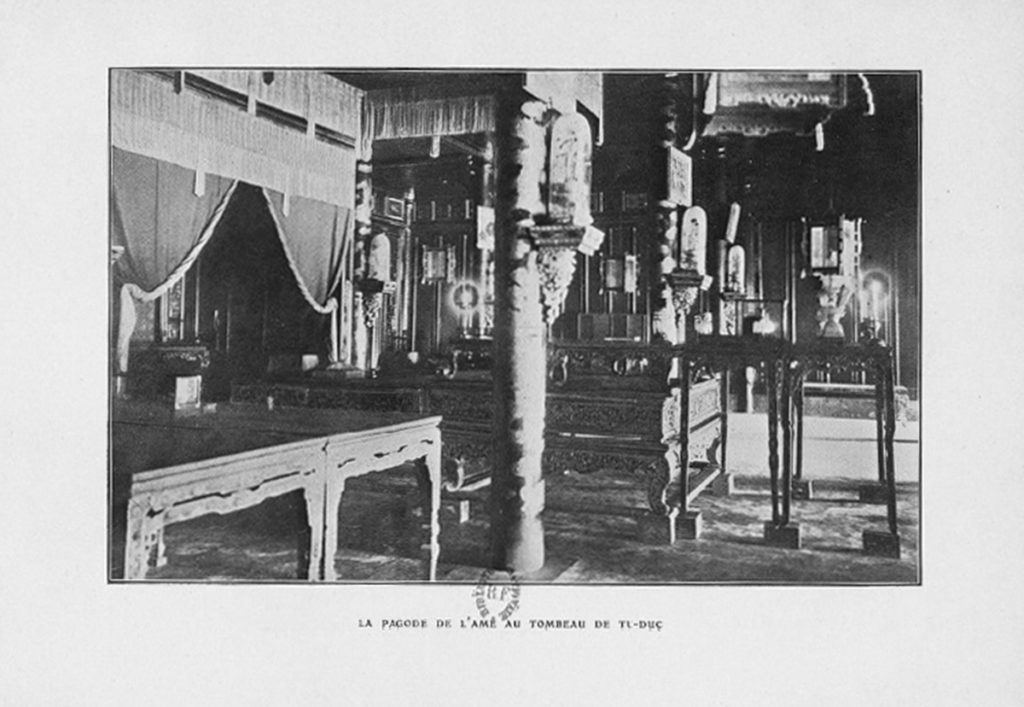

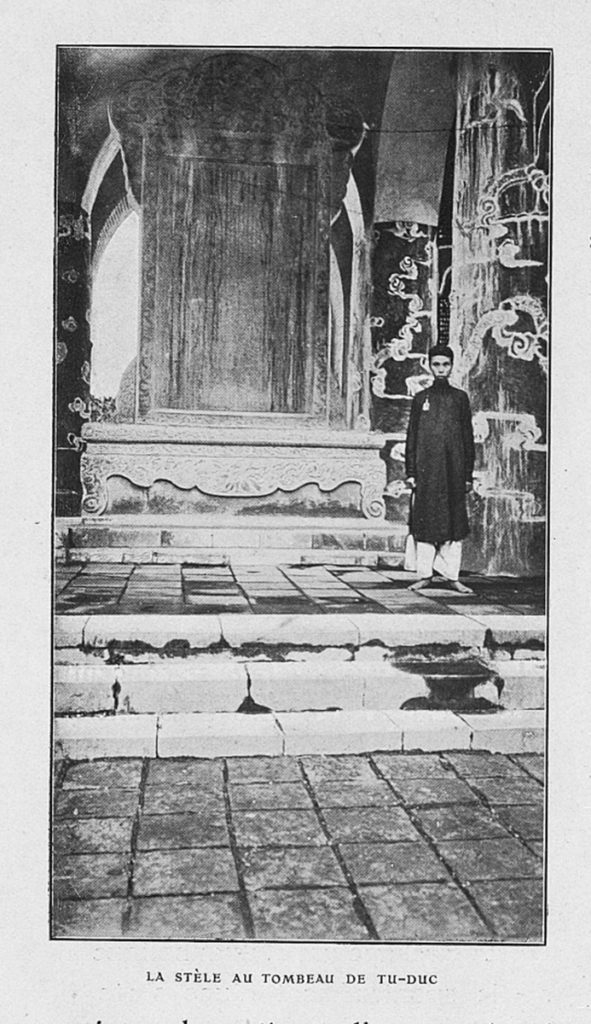

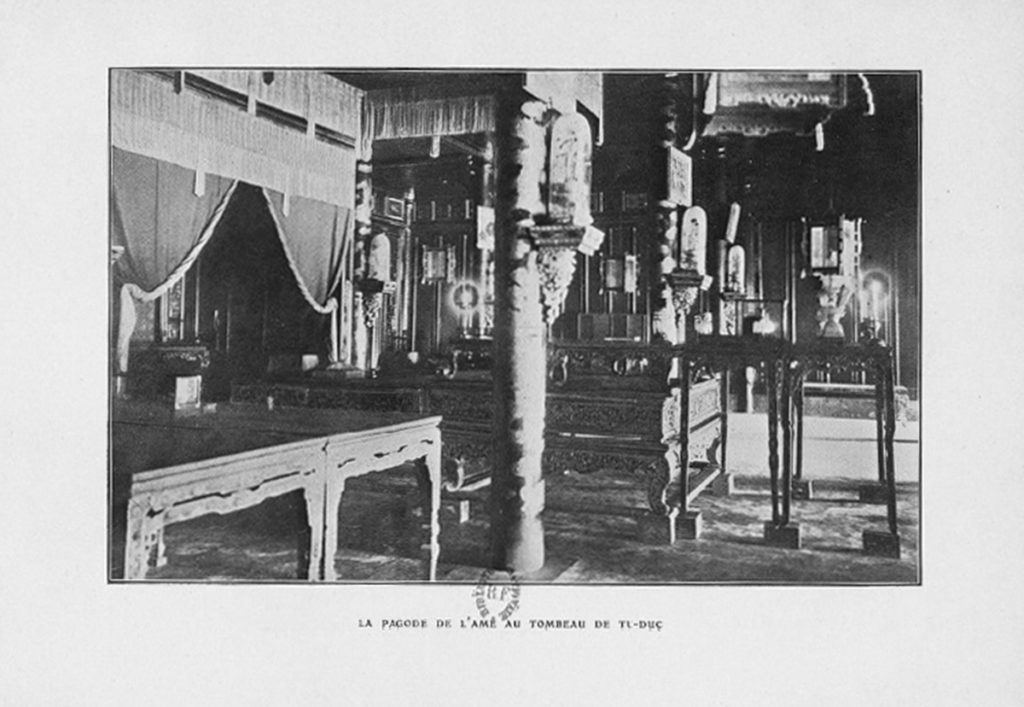

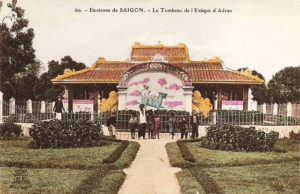

The Buddhism of Annam, strongly influenced by Taoism, accords a formidable appearance to the tombs of the great. These are subdivided into various different areas, each with a monument of profound significance, and it is their ensemble that forms the tomb. Every man must be considered according to his physical person, his private soul and his public life, so each emperor’s tomb presents three distinct elements – The Tomb, the Pagoda of the Soul and the Stele which traces the highlights of his reign.

The Tomb is ritually inaccessible. It is concealed beneath a large mound planted with trees, shrubs and flowers, crowned with a strong enclosure of stone closed off by a barricaded and padlocked gateway.

The Pagoda of the Soul houses an accumulation of rare and precious objects. In front of the veiled altar, where a symbolic tablet rests on a carved ancestral altar, lie all the items which give a complete and precise account of the deceased’s intimate habits – his favourite books, his own literary works, his betel chests, his tea sets, etc. Old royal favourites or former ladies in waiting from the court stand silently on watch in the soft shadows. They are charged with scrupulously observing the rites, of maintaining with one thousand attentions all the signs of his survival, of continuing to assure to the eternal soul of the departed a residence of luxury and repose, populated by graceful symbols, favourable to noble reveries.

The three essential elements of an imperial tomb are always complemented by an annex called the Pavilion of the Throne. This lightweight and in no way obituary construction commands a view of the entire site. During his lifetime, the emperor would have come here to take relaxation by reading works of high philosophy and following the progress of construction of his palace of eternity.

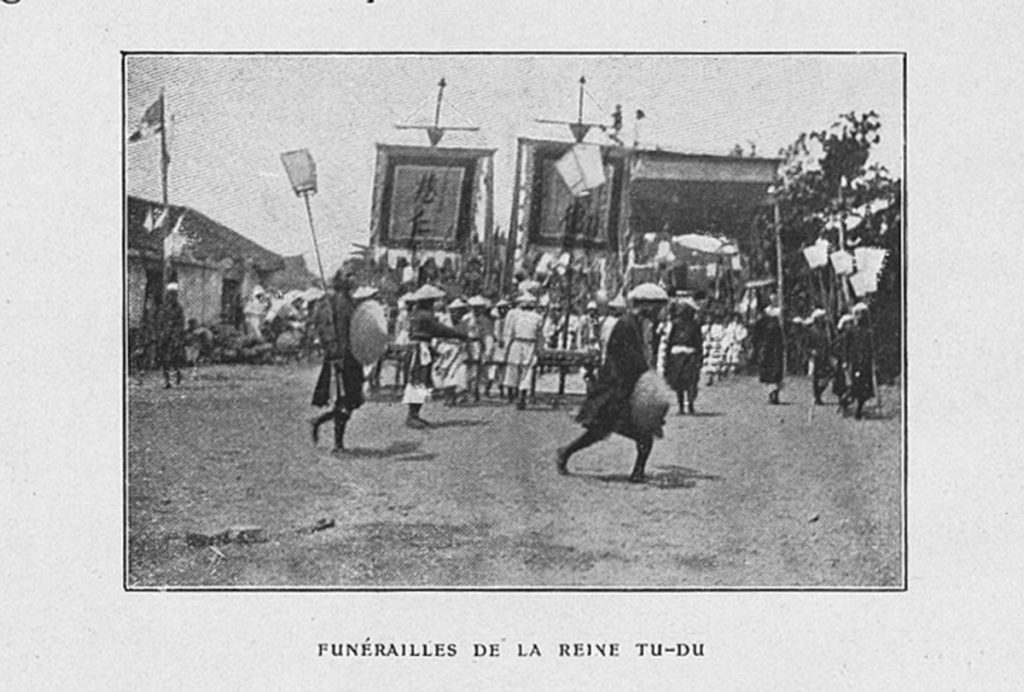

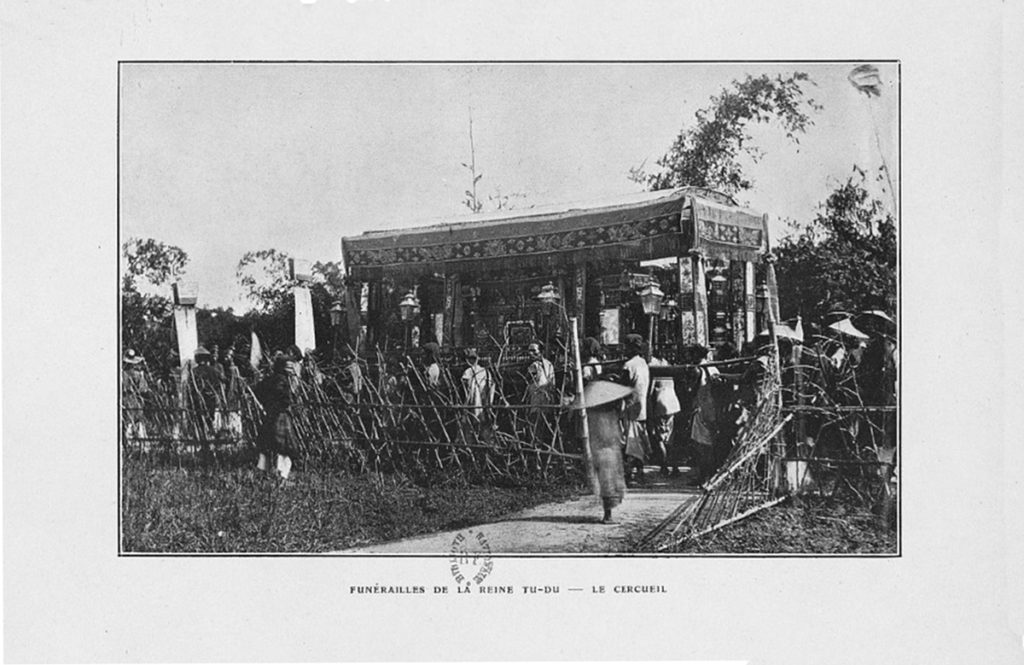

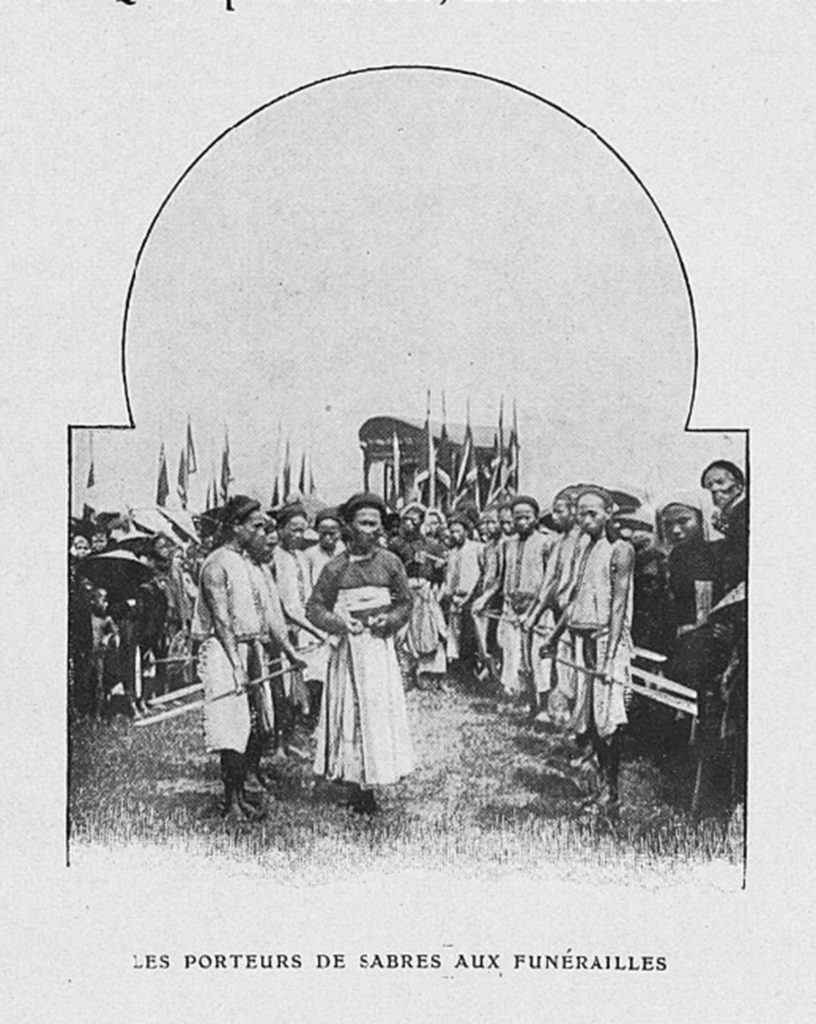

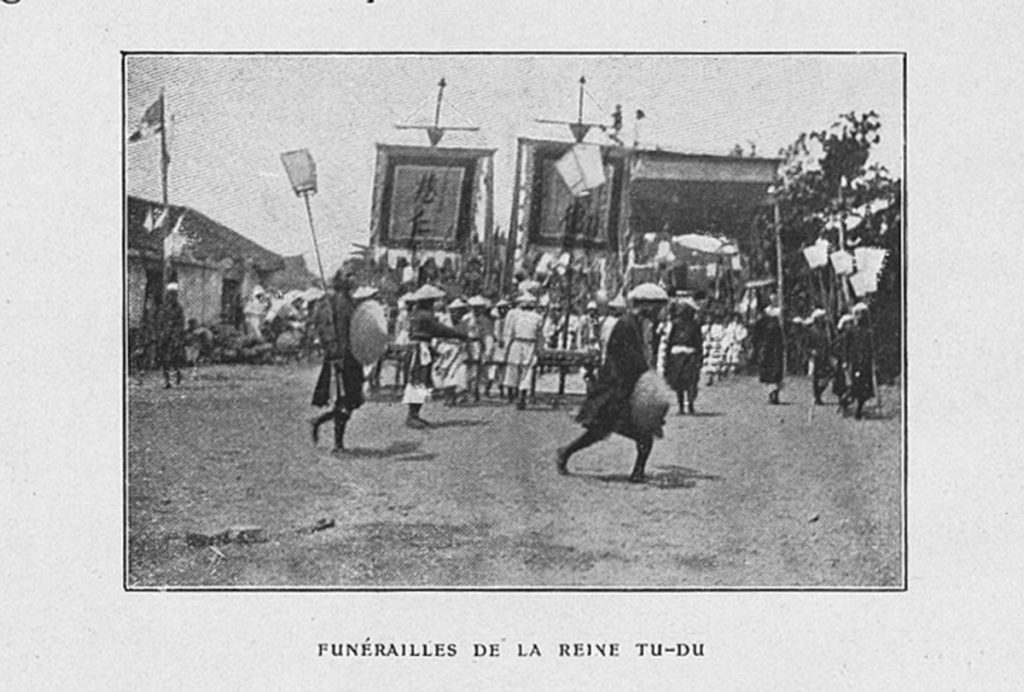

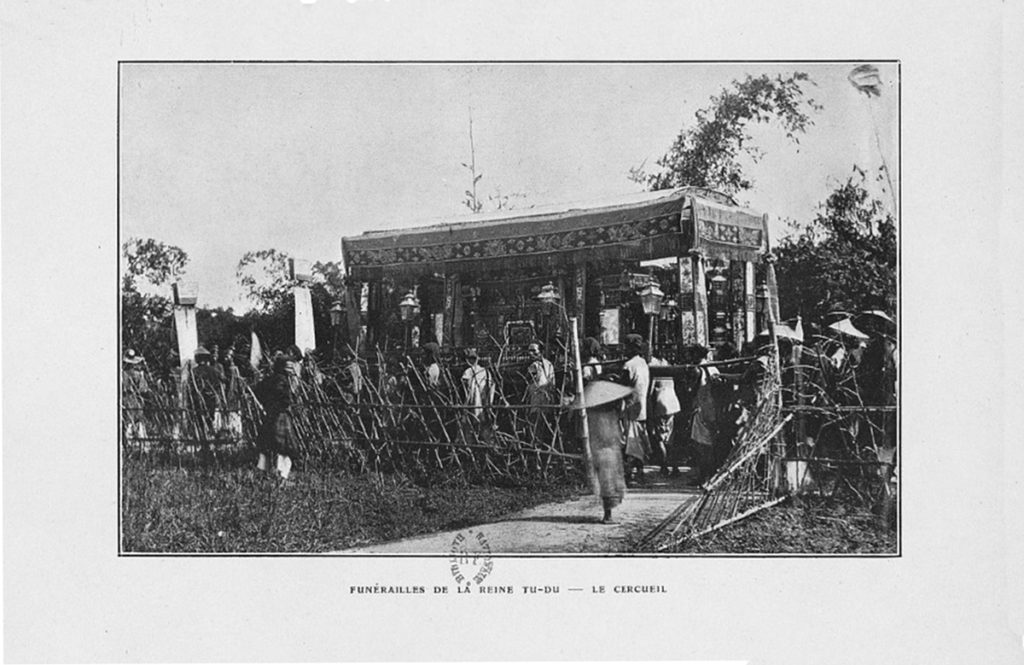

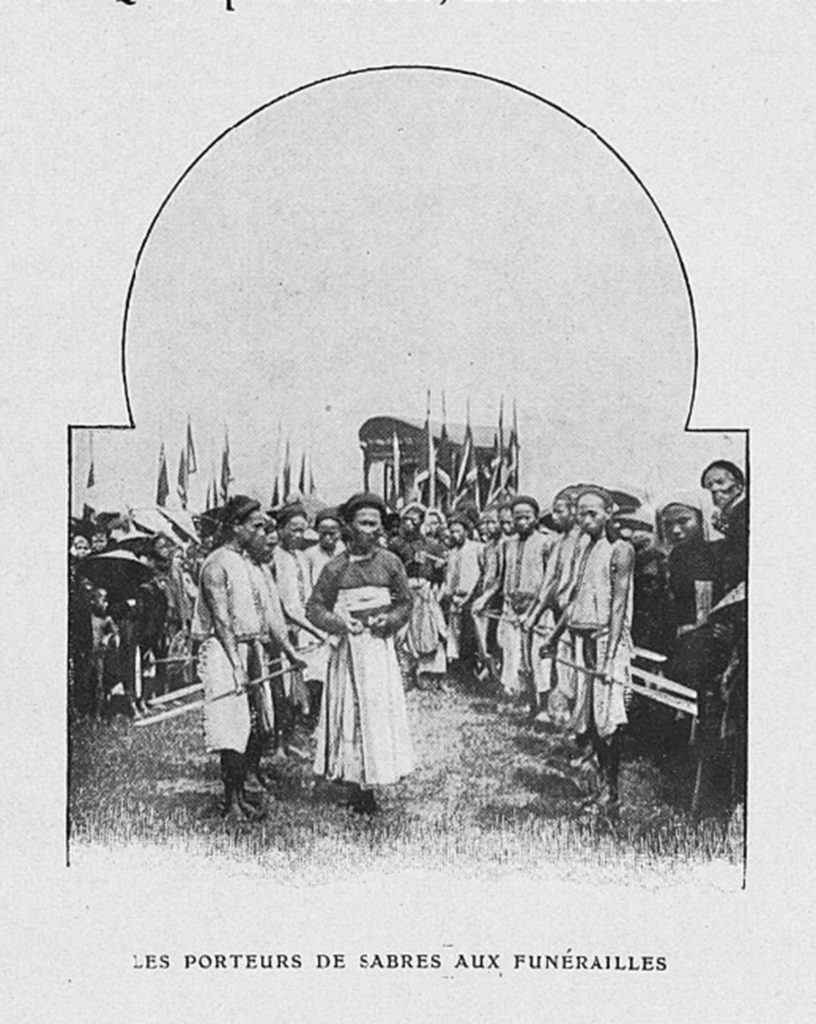

We can guess that royal funerals at the court of Annam display a splendour corresponding to the sumptuousness of the tombs.

The last ceremony of this kind dates from the month of July 1901. That was when the old Queen Tu-Du, wife of Thieu-Tri and mother of Tu-Duc, passed away. Her funeral lasted a whole day. At the outset, an endless procession wound its way at length through the broad avenues of the Citadel. The coffin was then taken to the Landing Stage and placed on a vast raft which served as a catafalque, crossing the Perfume River under the escort of a flotilla of sampans of honour, each carrying members of the great mandarin families. On the right bank, the procession was reconstituted and continued its journey to the tomb of Thieu-Tri, where the old queen was laid to rest near her husband. The two souls, symbolised in two precious tablets engraved with sacred characters, were placed side by side on two altars of twin ancestors sheltered in the same temple.

The Nam-Giao Festival

In the graceful countryside of Hue, where the melancholic sighs of the maritime pine bring to mind the sobbing of inconsolable lovers, two other manifestations of royal architecture still call our attention:

One is the Arena, or, more exactly, the fighting pit for elephants, panthers, tigers and buffaloes. The walls of this pit are now crumbling and abandoned. Since the court no longer supports the great barbarous pomp which these evocative games of Rome and Byzantium once contained, the Arena has already become a distant memory.

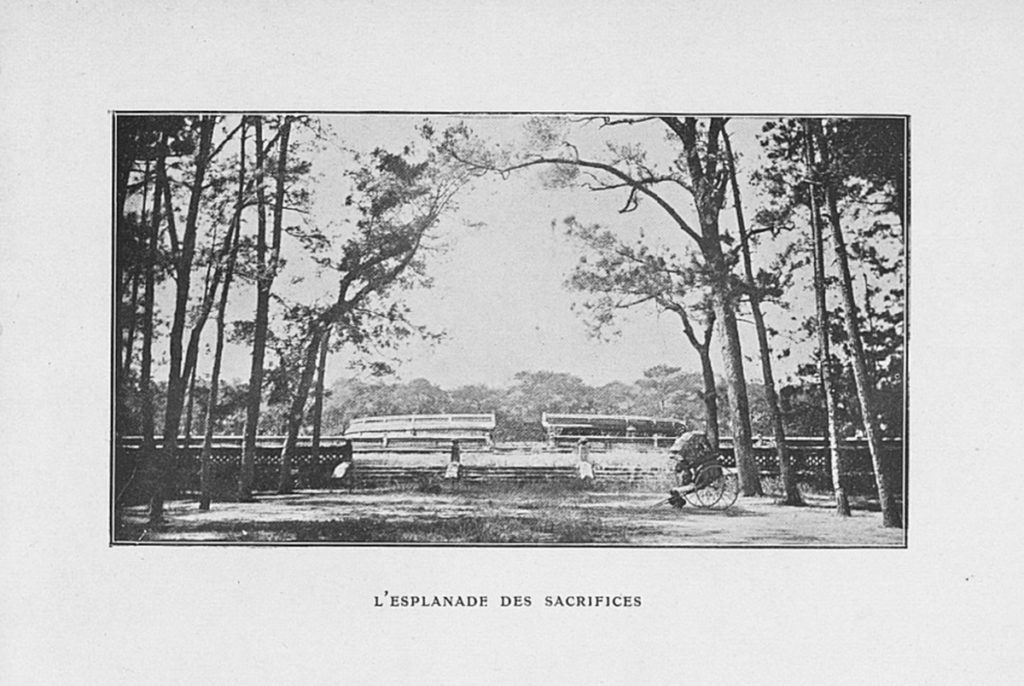

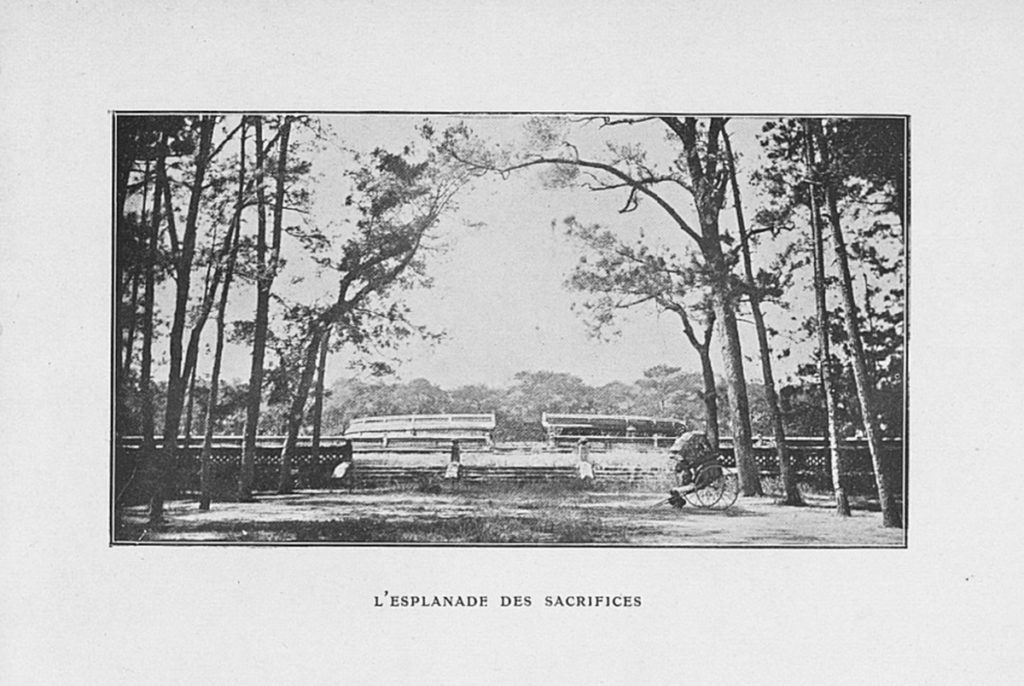

Of greater significance is the Nam Giao Esplanade or Esplanade of Sacrifices, a large terrace of square stone, bordered with balustrades, containing another circular raised enclosure. The whole is framed by a beautiful forest of regular, distinct and symmetrical pines. Each of these trees represents an important mandarin personality of the court, and Asiatic superstition is pleased to draw omens from the height of their trunks and their proud verticality, or, on the contrary, their cheeriness and the indolent inclination of their branches, smothered by vigorous neighbours who forbid the access of light from the sun….

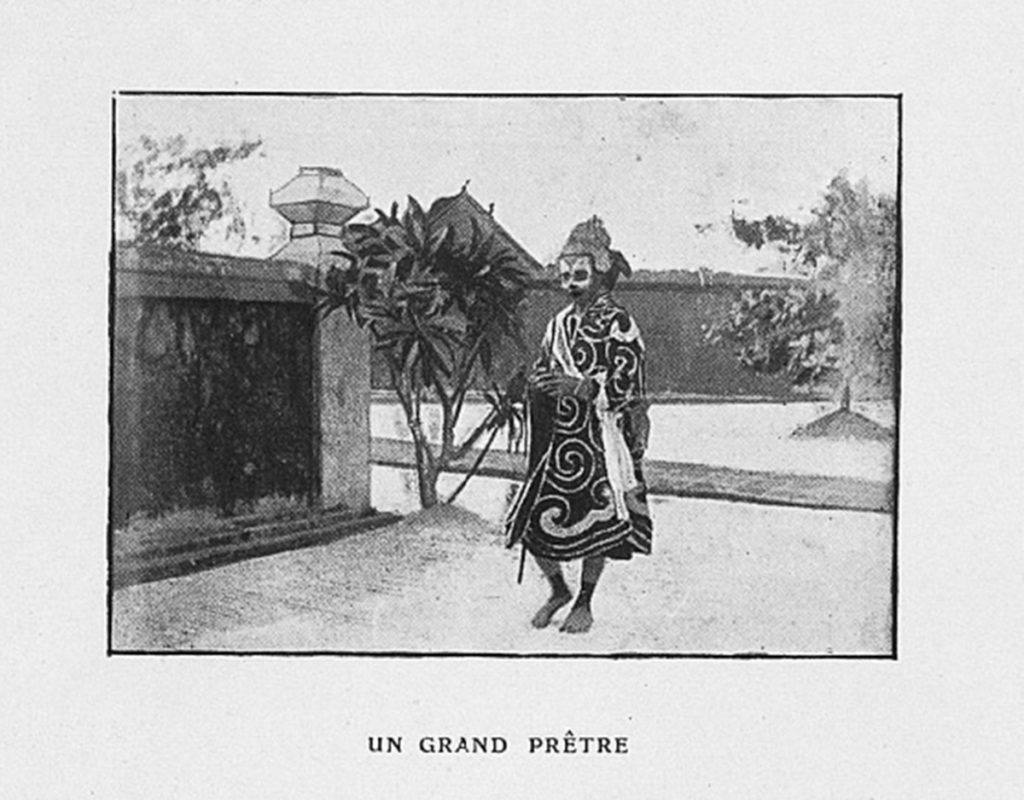

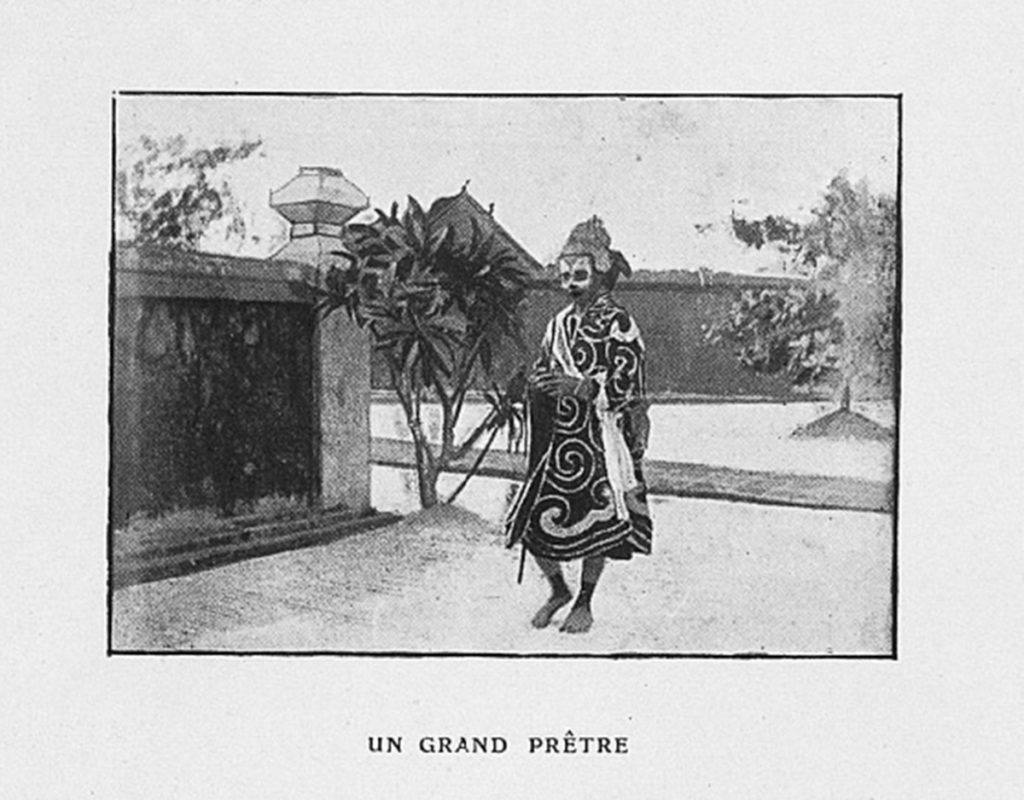

On this Esplanade is celebrated, every three years, the nocturnal Nam Giao Festival, solemnly presided over by the emperor in the guise of great priest. On the night in question, the monarch emerges at sunset from the great neighbouring pagoda after completing a holy retreat of 11 days. Large buffaloes, slaughtered and skinned, are arranged symmetrically across the flagstones along with a bloody garland of slaughtered pigs, calves and poultry. Countless altars carry offerings of fruits, choum-choum (rice alcohol) and precious objects. The night passes in prayers, which, from the first murmur, swells and grows to become clamours and vociferations. Flesh and bones are burned in pits, more beasts are slaughtered and spirits are invoked on the broad esplanade, now awash with blood and bathed in moonlight. At first light, the ceremony ceases and delegated notables of the villages carry away quarters of meat for more intimate rejoicings.

How much more graceful and idyllic is the Spring Ploughing Festival, which puts in the patrician hands of the young emperor the handle of a gilded and sculptured plough, with which he traces a hesitating furrow before his prostrate people, who thank the Buddha for his benevolence.

*****

Tourists, hurry! Because Hue, that delicate and fragile watercolour, is already pale and faded, and will soon surely disappear in the civilising whirlwind. Hasten there now, while there are still some vestiges of the vanishing Annamite empire to be seen.

The ruling classes of Annam are delicate, refined and cruel. They love pleasure, and are happy to expend minimal effort in all things. The Annamites will not be remembered as a civilisation which defied the centuries and commanded respect as conquerors. The history of this people will be heralded not by great stone monuments but through literary works on silk which enunciate philosophical truths and sacred maxims. A subtle intellectuality reigns amidst the silence of the tombs and in the soft shade of the pagodas. When the old literati with their fine silver beards, mummified in their robes of silk and gold, proclaim in their ghostly voices the winners of the triennial mandarin examination, we are gripped with sadness and regret by the thought that conquest and progress on one side and conservation on the other are difficult to reconcile.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

Bursts of artillery exploded upon the ramparts, and bugles rang in the fields, as our Résident-Supérieur, M. Rheinart, followed the civil and military officials by standing in attendance before the throne.

Bursts of artillery exploded upon the ramparts, and bugles rang in the fields, as our Résident-Supérieur, M. Rheinart, followed the civil and military officials by standing in attendance before the throne. He responded to M. Rheinart’s speech in a crystal clear voice. The French officials then retired to let the mandarins do their laïs. At the front of the throne room were the princes; beside them were the ministers and great dignitaries, and finally all the other mandarins.

He responded to M. Rheinart’s speech in a crystal clear voice. The French officials then retired to let the mandarins do their laïs. At the front of the throne room were the princes; beside them were the ministers and great dignitaries, and finally all the other mandarins.

held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”

held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”