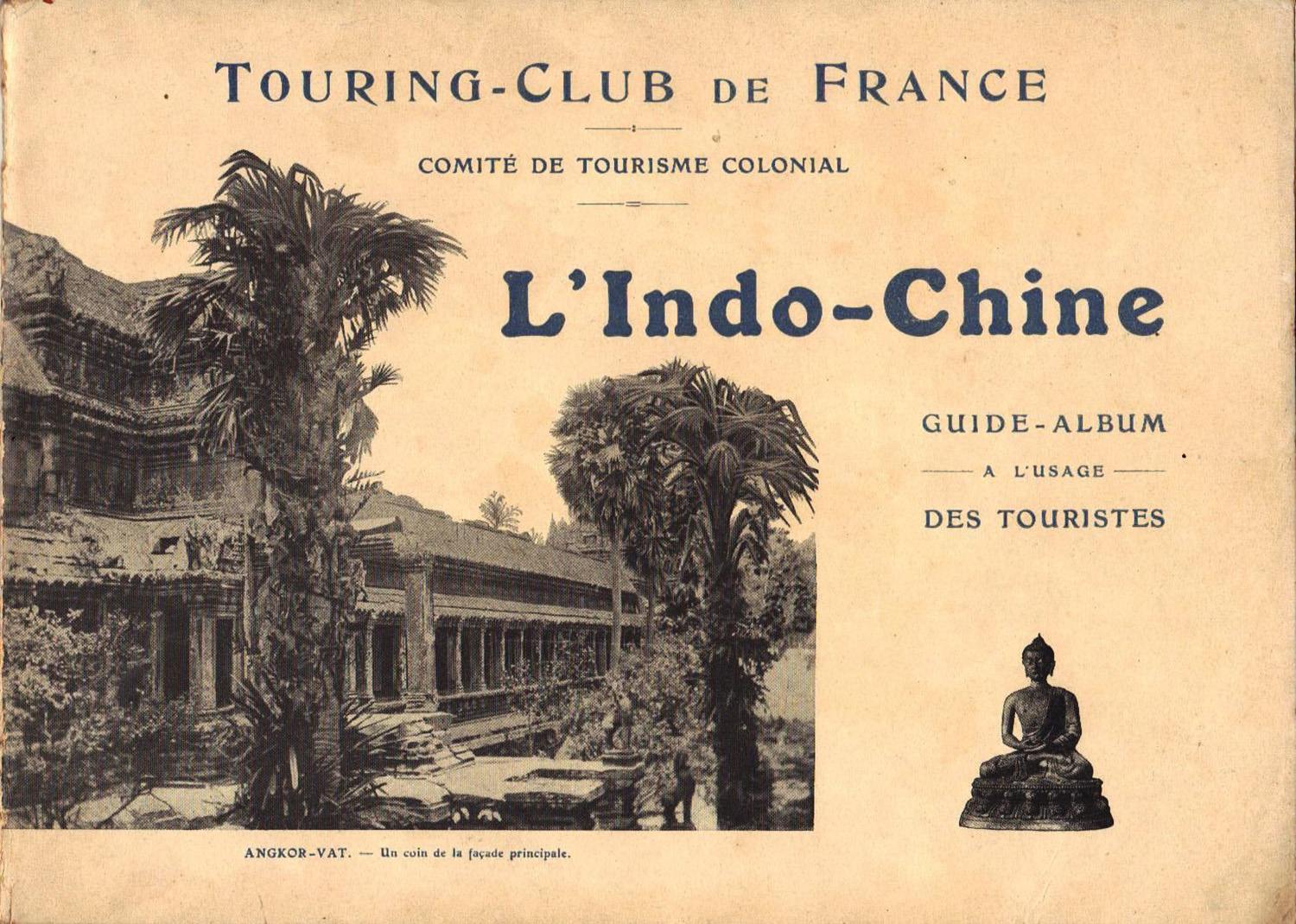

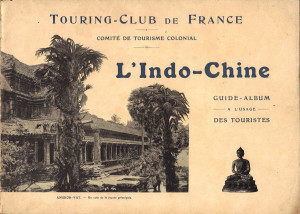

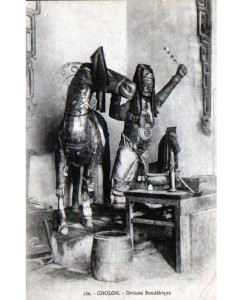

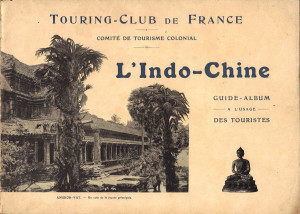

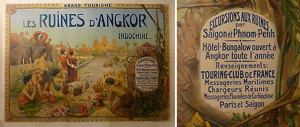

The Touring-Club de France Indo-Chine guidebook-album of 1913

Up to now, our colonial empire – Algeria and Tunisia excepted – has played a negligible role in the immense tourist movement which has already transformed many other parts of the world where it already represents an economic factor of primary importance.

This fact is especially striking in Indochina, where it takes on the character of a major economic deficiency.

Some clarifications are needed to support this assertion:

Indochina is located in a part of the world where the intensity of tourism is considerable. This is affirmed by the figures cited below, which are drawn from the most direct and reliable sources.

The Trans-Siberian railway line

By a quite explicable phenomenon which it is important to note first, the Trans-Siberian railway line, far from competing with the shipping companies and harming tourism in Southwest Asia, has on the contrary favoured it. Today we may say categorically that the new rail route has permitted travellers to the Far East to complete their tour of East Asia without the need to make a long and repetitive return journey by sea.

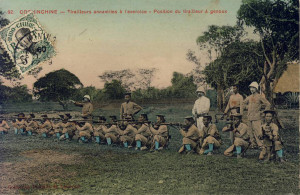

At present, Japan annually receives around 20,000 tourists; Java 8,000; and the Philippines 4,000.

To these figures one must add, to the number of people likely to be interested and attracted by Indochina, a portion of the 25,000 tourists who travel each year to India.

However, in the presence of this data, we experience some embarrassment to admit that the number of visitors received annually by Indochina in recent years has never exceeded 150!

That figure alone is enough to characterise the weakness of our efforts to date in the field which concerns us here; just as it shows the importance of developing a programme to rectify the situation.

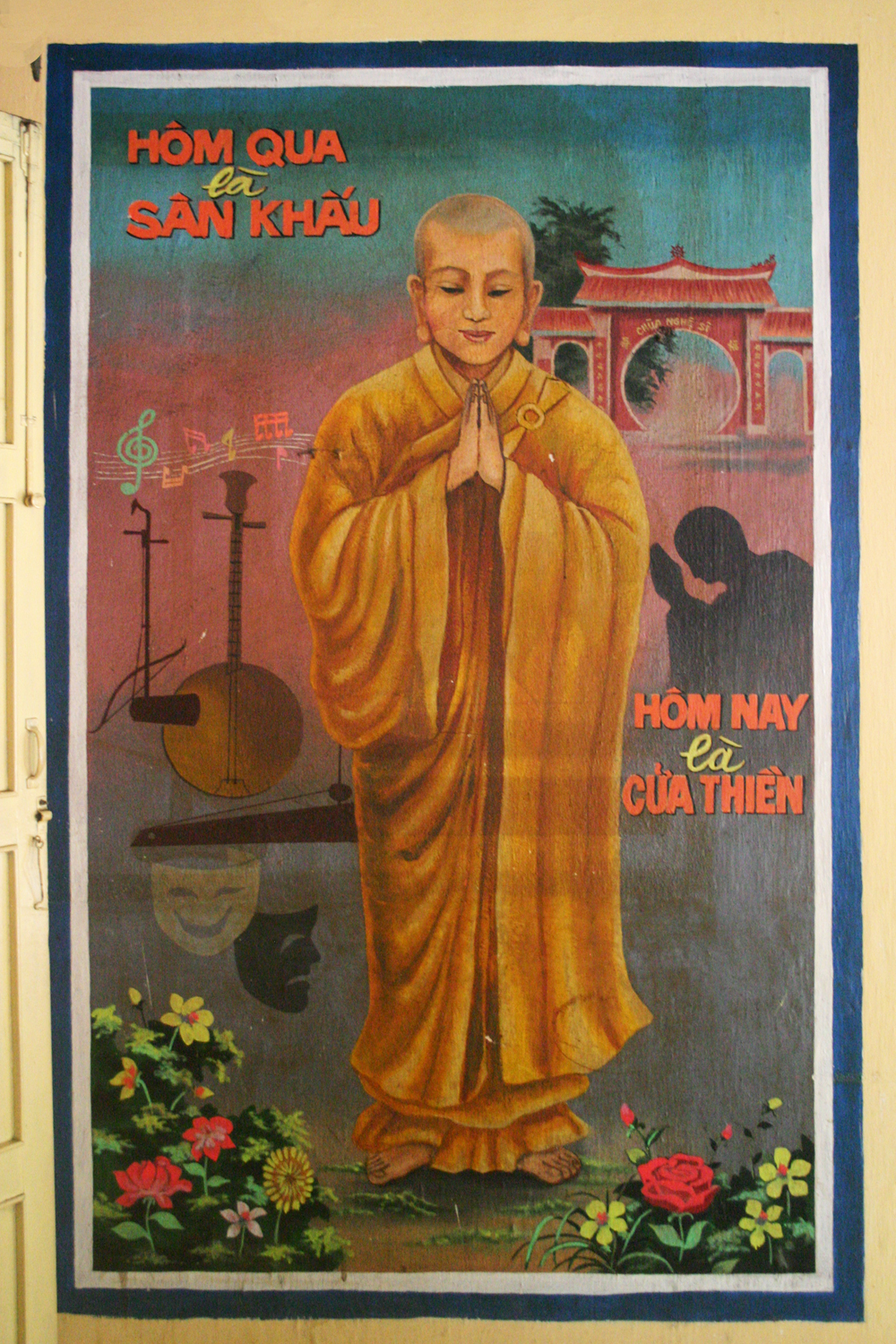

Cherry blossoms in Akasaka, Tokyo

Japan is a country whose charms and sights are famous, but they are unquestionably inferior to those of Indochina; neither can Java, where in reality there is a lot less to see than its well-established tourist publicity maintains, support a comparison with our colony.

The Philippines attract 4,000 tourists each year; these are exclusively American citizens who wish to know the new colony of their Union.

As for India, there we find a long established current of tourism, recruited from a global clientele for whom this trip has somehow become a “classic” one.

What is obvious is that, amidst this considerable tourist activity, the same participants must be counted more than once, because many of them obviously feature in the statistics of the several different countries they pass through during one overall excursion.

However, these same tourists gravitate around Indochina, passing near its coast, staying in Singapore and Hong Kong, without our colony experiencing any benefit from their presence.

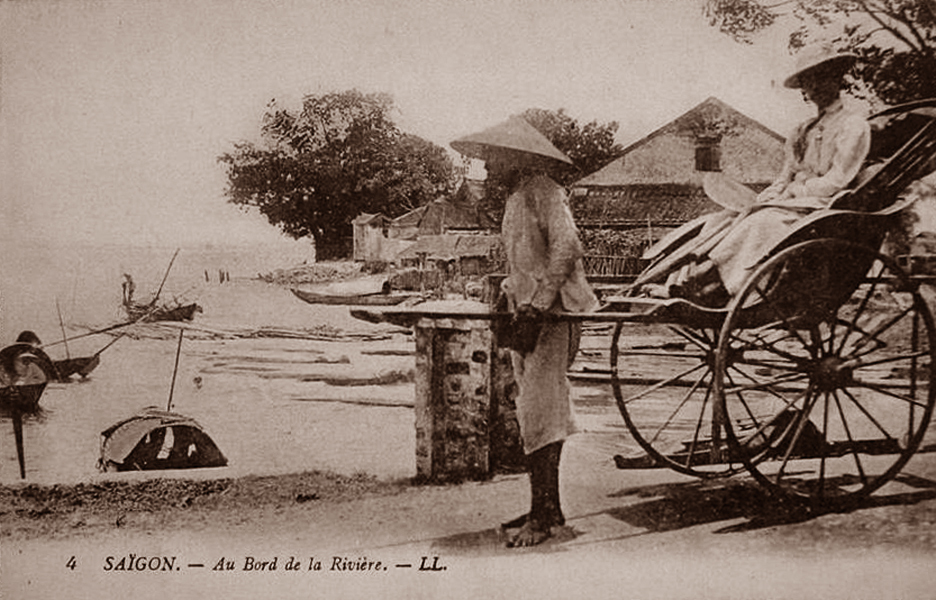

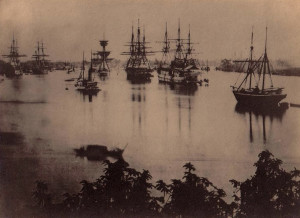

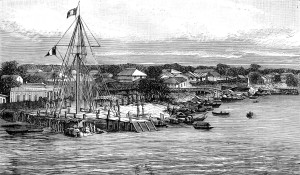

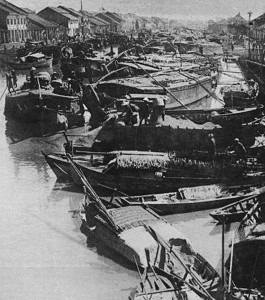

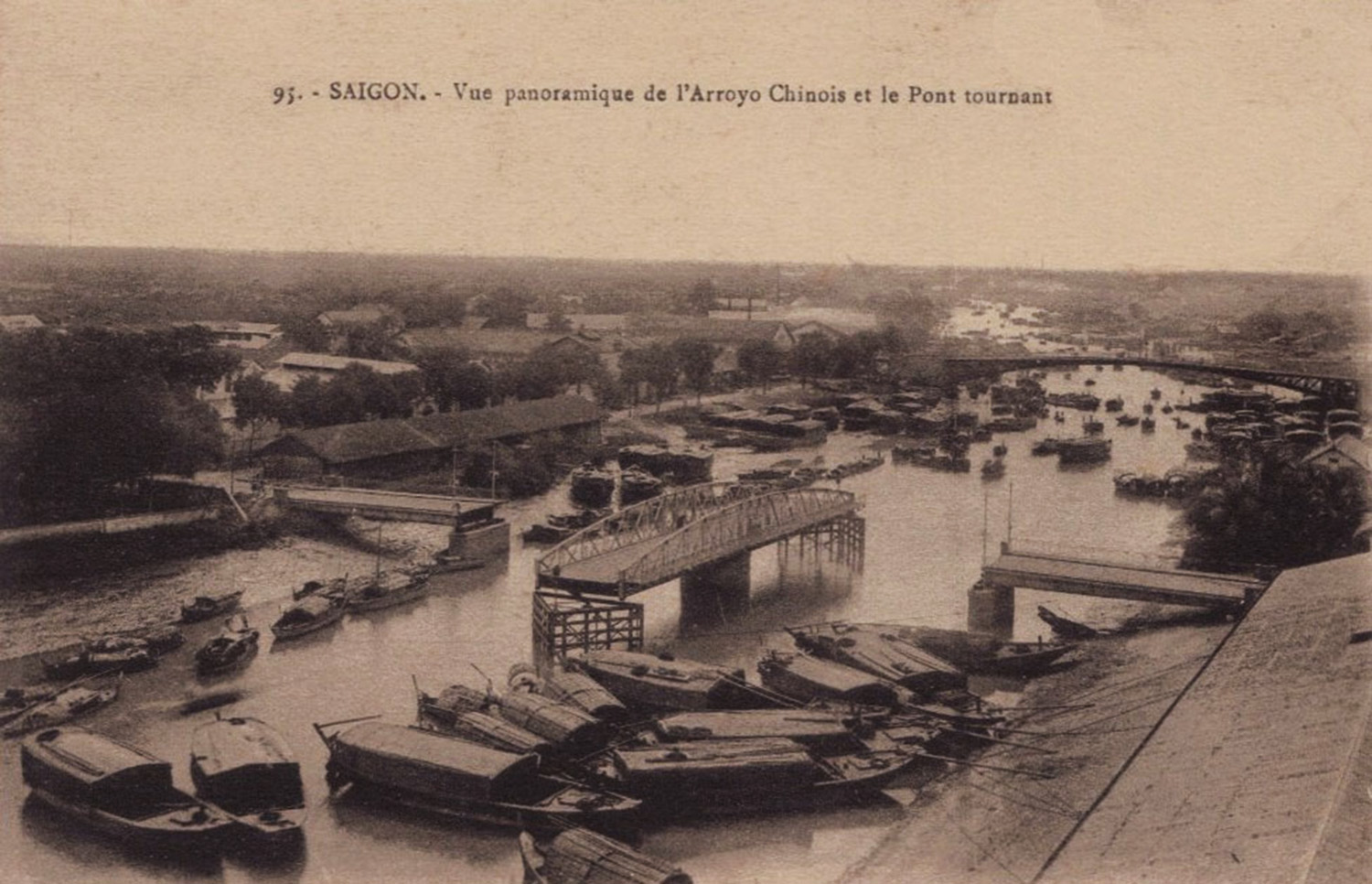

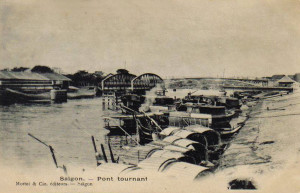

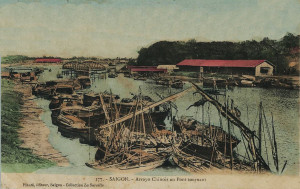

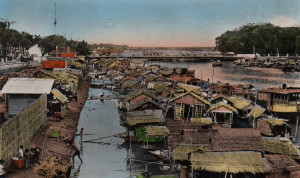

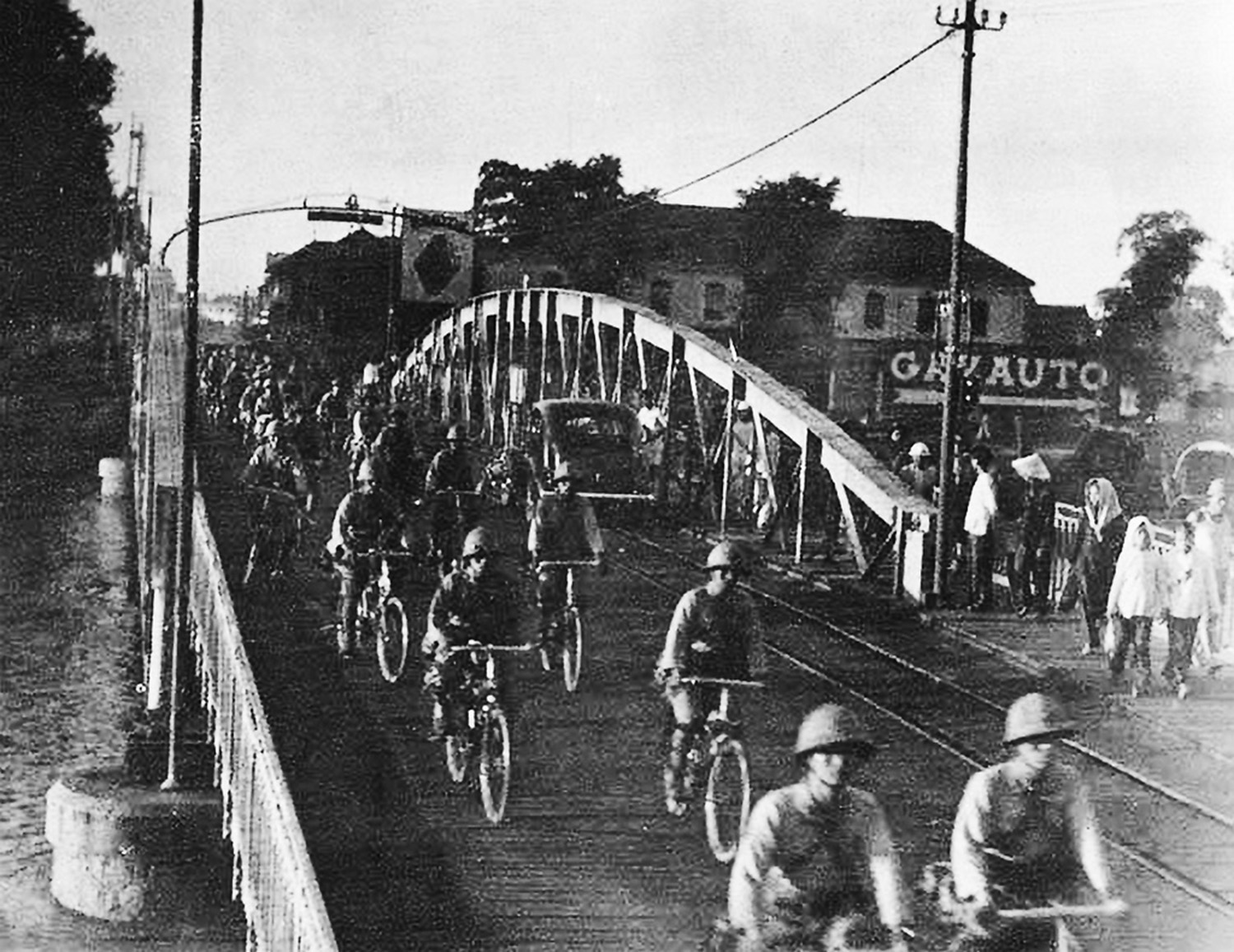

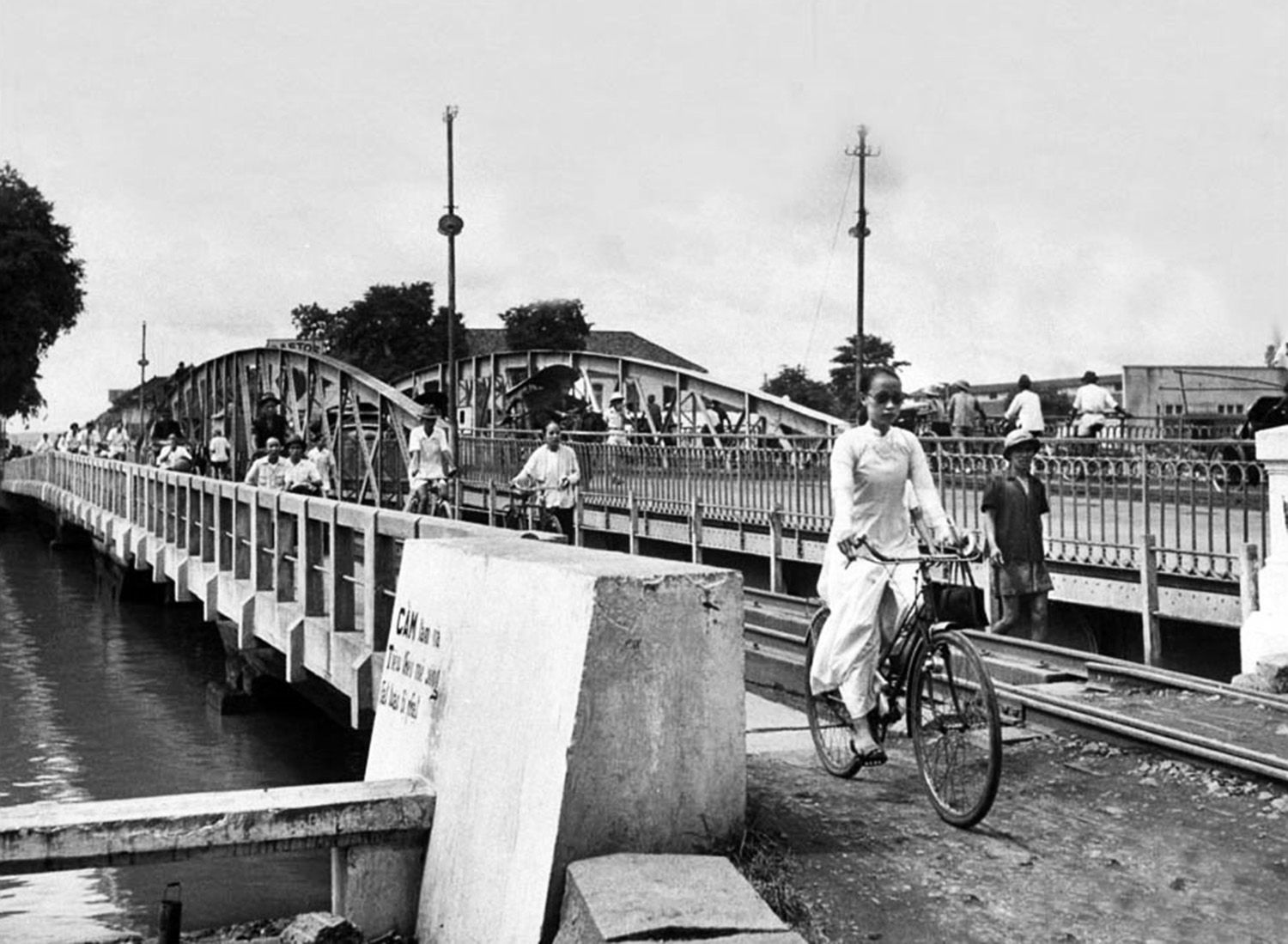

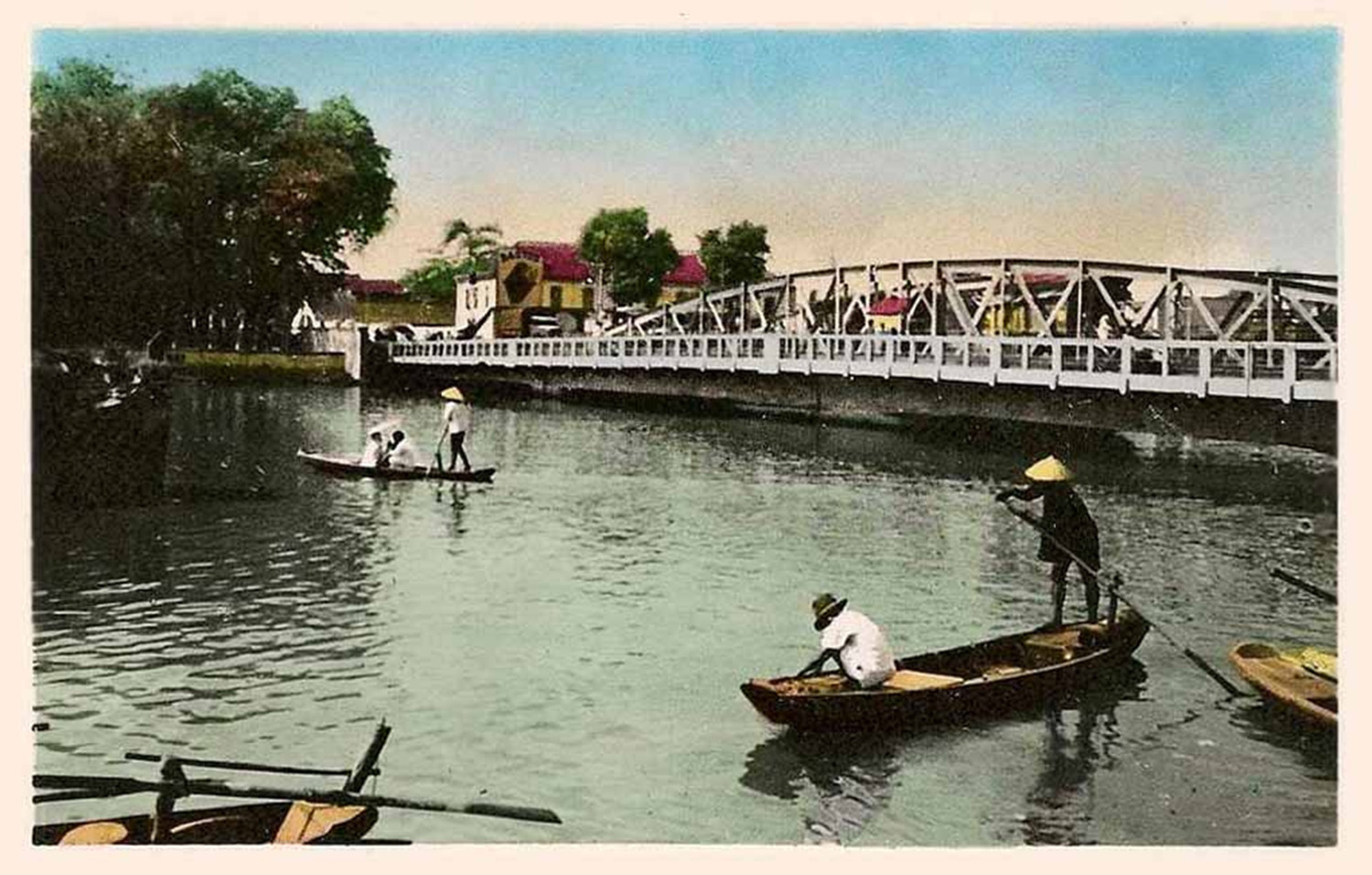

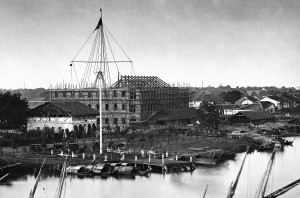

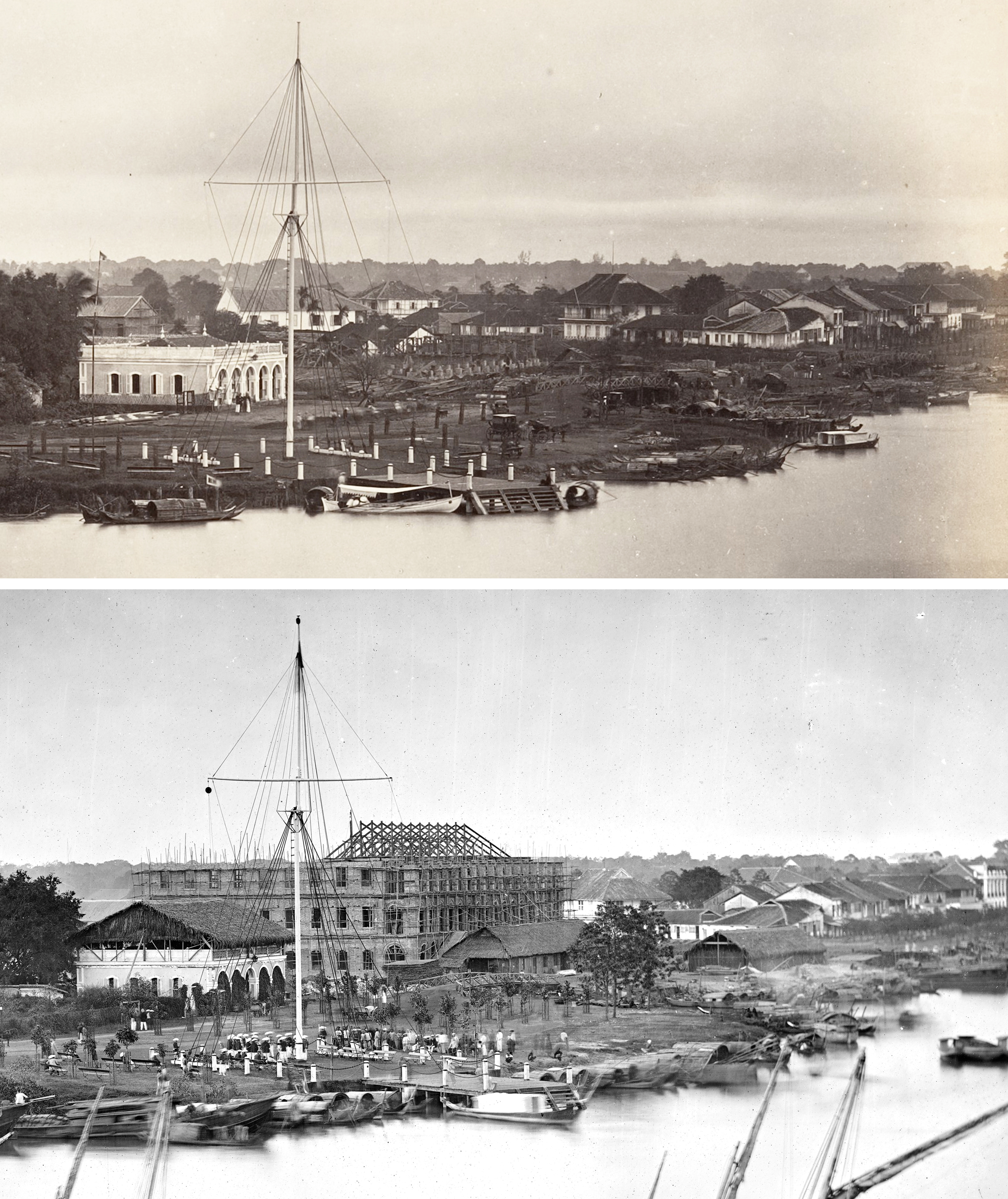

Sampans in Saigon harbour

The reason for this situation is not difficult to identify: it is simply that up to now, no-one, either in our colonial world or back home in the Metropole, has given any thought to the shocking contrast which exists in this respect between our possession and neighbouring countries; and as a consequence we are viewed with indifference and disregard by international tourists.

One can, however, affirm that no country possesses, grouped together in one land, as many architectural, artistic and natural wonders as our Indochina: wonders made even more remarkable by the fact that each of these wonders is unique in the world. Potentially, therefore, they accord in an absolute and very timely manner with the famous “Best in the world” category so dear to Americans, which justifies above all in their eyes the nature and value of a touristic attraction.

If our rivals in neighbouring countries have attained such remarkable results while our tourism industry is still in its infancy, this simply reflects the determination of those countries over many years to draw a practical and profitable advantage from the wealth factor represented by the tourism industry. For us, however, this was never a major concern; it took a very long time here – almost until the very last days preceding the Great War – for the potential value of tourism to be realised, and even now it remains largely neglected, while others at the door of our Asian Empire stage a wonderful party.

Manila Customs House, Philippines

The results obtained by our Asian neighbours in places like Japan, Java or the Philippines, are not the work of individuals alone. In these countries they have organised tourism rationally, somehow even scientifically; they knew how to transform this sector into a powerful state industry.

They have not only equipped their countries to receive an influx of foreign visitors, but also spent time studying how to attract them and get them to visit.

They have prepared beautifully produced publicity brochures, regularly updated and always in plentiful supply wherever they may be read by the prospective visitor.

Obviously some spending was required to put all this into action, but that spending was infinitely inferior in amount to the sum we might assume.

One searches in vain, on our side, for an equivalent initiative.

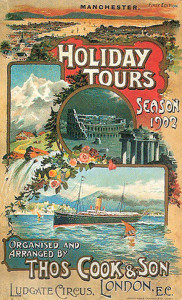

A Thomas Cook & Son poster from 1902

And if Indochina can only boast 150 visitors per annum beside the approximately 50,000 who trek through neighbouring countries, it is simply because, neither in France nor in the colony, have we ever taken the trouble to inform that potentially enormous market about the beauties our Asian domain can offer, nor to equip our colonies to receive the tourism movement thus set in motion.

A typical fact which I have personally observed demonstrates the validity of this assertion: one would search in vain for the smallest mention of Indochina on the itineraries of any of the multiple and important travel agencies which have houses around the world, such as Thomas Cook, or the large American firm Raymond and Whitcomb.

In the hall of the Banque de l’Indochine in Saigon, a stack of brochures is made available to the public. I once flipped through them, in idleness as much as curiosity, pending the completion of the banking transaction for which I came. They contained publicity, well understood elsewhere, in favour of destinations such as Chicago, Santa Fe, California. A publication of the Pacific Mail entreated globetrotters to visit Manila, Honolulu, Russia, Japan, China, Java and India. Not a word about our incomparable Indochina, even though all travellers to this region must pass near it in order to make these trips! It is completely ignored. Neither is there any further trace of the beautiful Indochina album, distributed free by the Touring-Club, which a few years back spent a large sum on this promotional item with support from the colony.

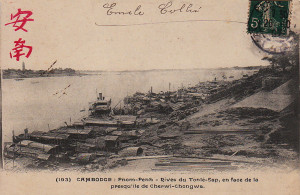

The banks of the Tonle-Sap river in Phnom Penh

I commented on this situation to a gentleman of the administration, who seemed so surprised that I considered it pointless continuing.

As long as Indochina remains outside the countries classified as centres of international tourism, tourists will not come. And while we fail to provide tourism publicity materials, our colonial domain will remain excluded from this movement.

An extremely vicious circle

It will serve us well, however, if we finally take full advantage of the wealth which our colonial action has assigned to us.

Moreover, one should not hide how far the general mentality in French colonial circles is alien to the most basic understanding of tourism as an economic factor. It’s as if the idea of an individual travelling for pleasure, without being forced to do so professionally, has not yet developed in the eyes of many colons. I can’t think without amusement of the number of times I have heard, from smart people, this Baroque thinking: “What? You travel for pleasure? Nothing obliges you to do so?” And my interlocutor looks at me with wide eyes, bewildered, as if to make sure I don’t have two heads, like the well known calf.

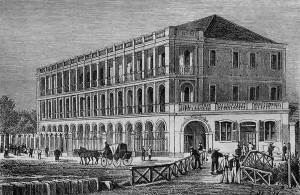

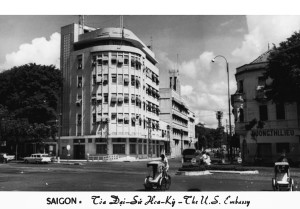

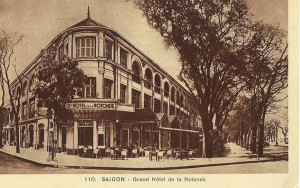

The Grand-Hôtel de la Rotonde, Saigon

In the Baron de Montesquieu’s great novel, it was commented: “Monsieur is Persian! How can one be Persian?” It seems that since that time not so much water has passed under the bridge as many people might claim.

On the day we decide to address practically and on a widespread scale the issue of exploiting tourism in Indochina, the first problem to deal with (except in a few places) will be that of the hotel industry.

Indeed, not only is the hotel industry the foundation for the tourist exploitation of a country, but its role is so important that it can, in certain cases – and examples of these are not lacking in other countries – have a material impact on tourist numbers.

In any plan to develop tourism for an entire country, the various hotel operations form a whole in which the diverse elements are interdependent. If one element is inadequately equipped, this inferiority affects the reputation of other elements in other parts of the country.

“This room is dirty,” said a tourist of my acquaintance to an Indochina hotel manager (an exception, I hasten to add). “So?…” replied the innkeeper without blinking. “Others slept well there, and they didn’t die!”

The outdoor restaurant of the Hôtel des Nations, Saigon

You will not accuse me of exaggeration if I assure you that this tourist had only one desire: to scuttle away without seeing any more of this place where the respect due to the visitor was conceived in so singular a way. After that experience, it is doubtful that he will become a hot propagandist for our Indochina!

Perhaps the best example is set by Corsica, a beautiful country just a stone’s throw from that part of Europe where, every year for several months, the great continental tourism movement is focused. Up to now, despite providing a few things properly from the point of view of the hotelier, we have been unable to profit from the great tourist movement which has become the fortune of the “Scented Isle.”

The beauty of Indochina

Indochina, as I have said, is a country which contains some of the world’s most wonderful and incomparable sights.

These, thanks to the efforts made in the last few years by the Touring-Club, are only now beginning to be recognised. It is not inappropriate to recall here their character and value:

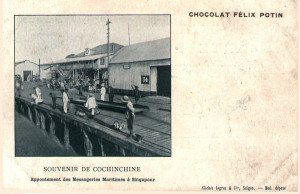

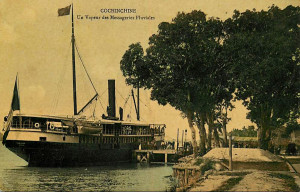

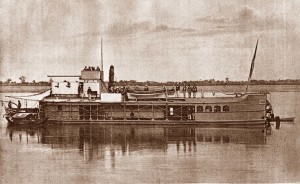

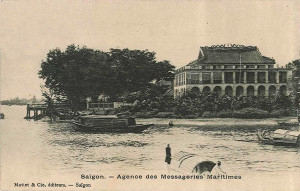

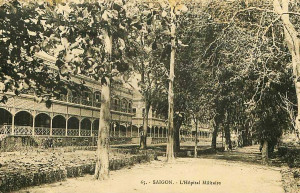

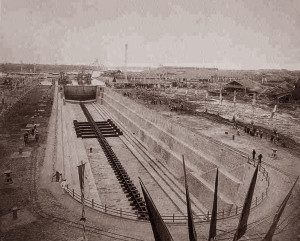

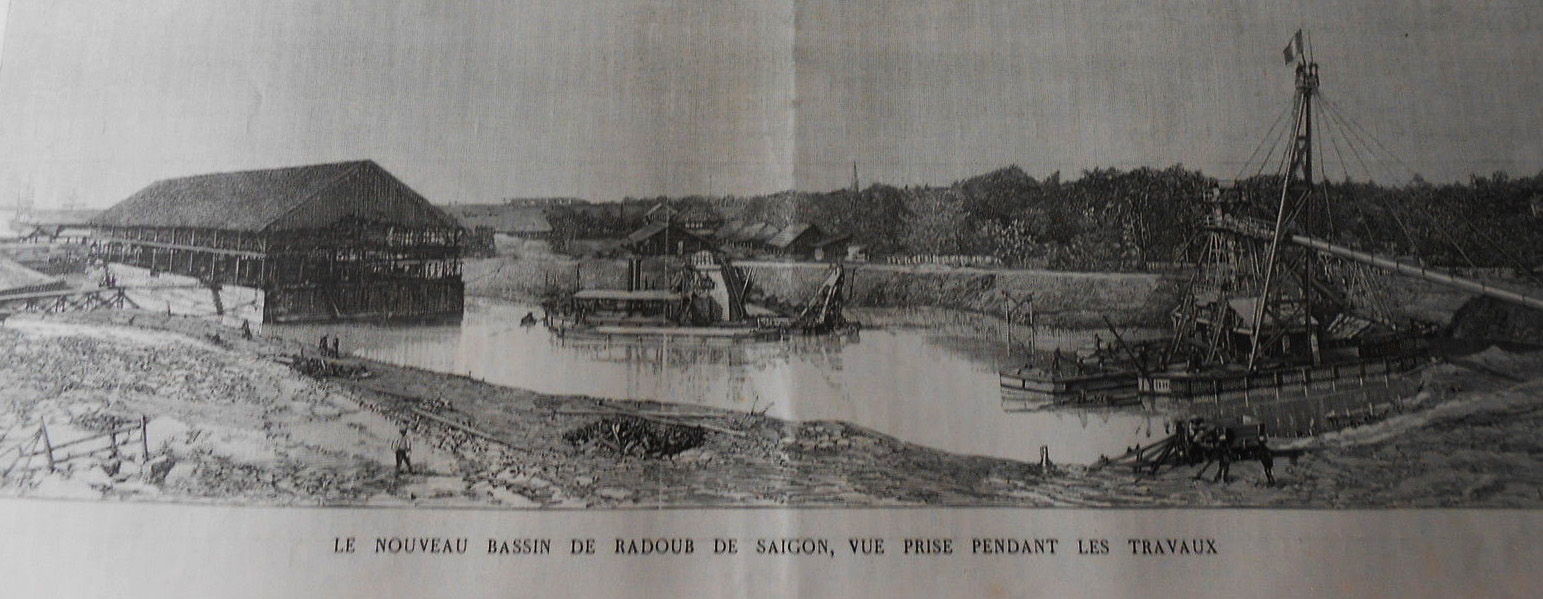

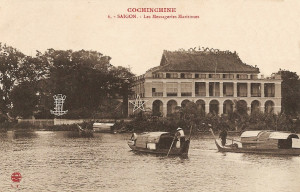

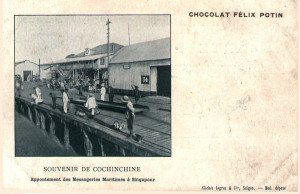

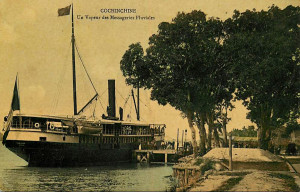

The Messageries-maritimes, Saigon

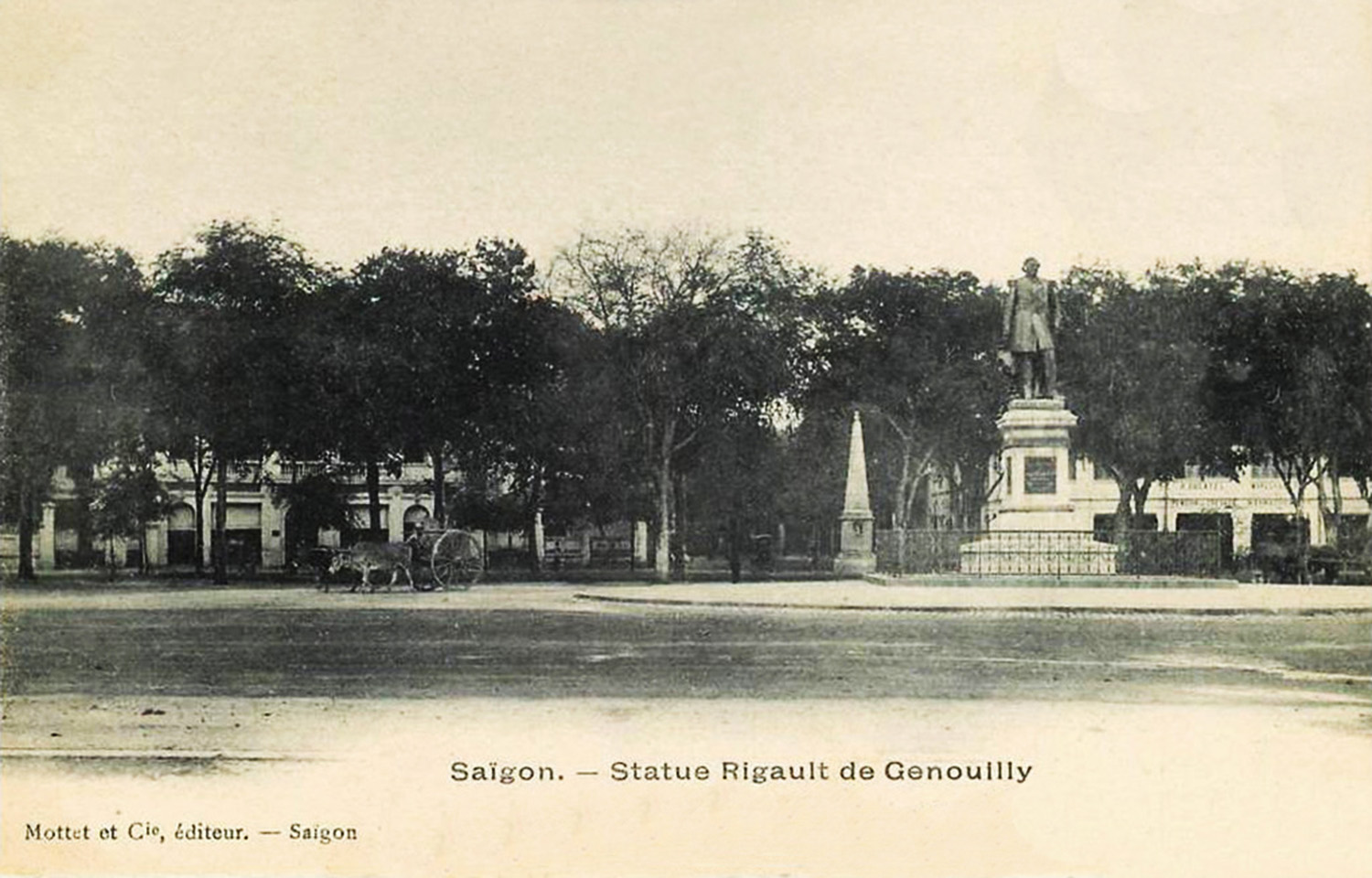

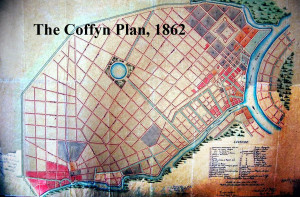

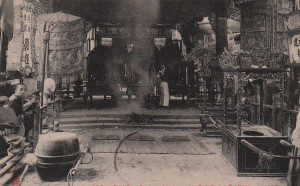

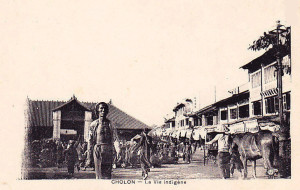

– Saigon, the beautiful city, centre of our influence in the Far East.

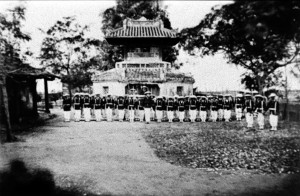

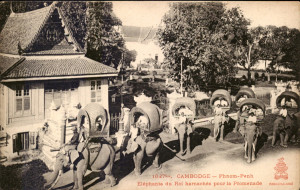

– Phnom Penh, with its palaces, its temples and its character.

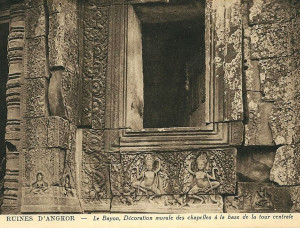

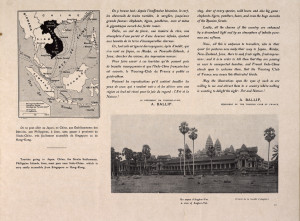

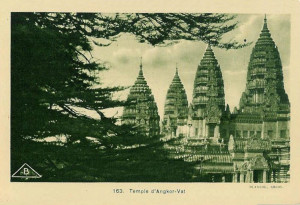

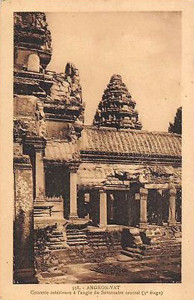

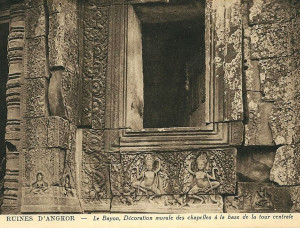

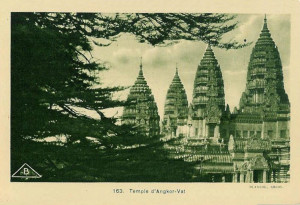

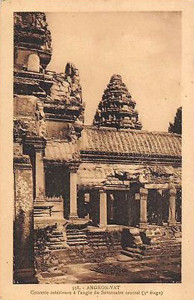

– The vast region of Angkor, whose magnificent monuments constitute, in a full ensemble of art and majesty, a splendour the equivalent of which we would seek in vain elsewhere, even in India.

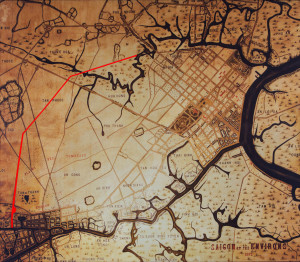

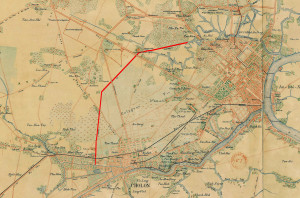

When I last went there, access to Angkor had been greatly facilitated by the extension of the Angkor-Siem Reap road as far as the Great Lake.

The current public automobile service may therefore, from this time, run directly between Angkor and the Great Lake.

A motorboat connects the destination of the automobile service with the anchorage for larger tourist vessels which ply the Great Lake.

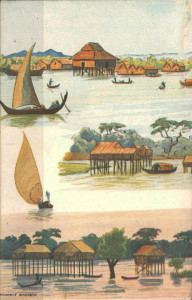

Fishermen’s huts on the Tonle Sap river

We have thus already come a very long way from the difficult conditions of the trip to the ruins described by Pierre Loti in his 1908 work Un pèlerin d’Angkor.

Then, for those whose time is not limited, there is Laos, which also includes many beautiful monuments, ranging from the grandeur of the rain forest to the splendid waterfalls of Khone. Laos, alone, would be worthy of attracting the elite of globetrotters worldwide.

There’s also Annam and its mountains, which unfold in front of the eyes of the visitors like unforgettable tableaux, whose character is accentuated by the presence of a diverse fauna found in few other countries.

The royal capital of Hue, with its tombs, serene majesty in a framework of high wooded hills, leaves an indelible memory for all those who have seen it; its curious Confucius Temple, the Pass of the Clouds, and the Marble Mountains complete in this part of our colony a rare set of tourism destinations.

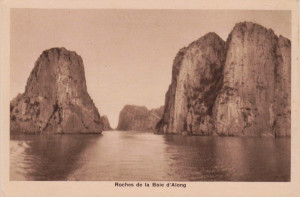

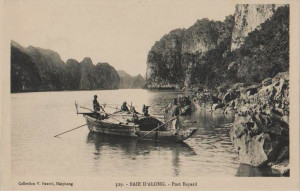

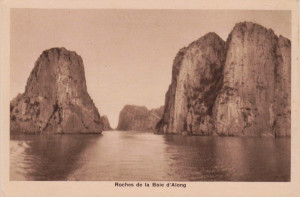

Finally there is Halong Bay, a wonder of nature, unique in the world, and whose spectacle is overwhelming in its grandiose severity.

Haïphong, a fine maritime city which has emerged from the Delta marshes.

Hanoï, our northern capital, so interesting to visit, with its large indigenous agglomeration juxtaposed with a new and beautiful French city.

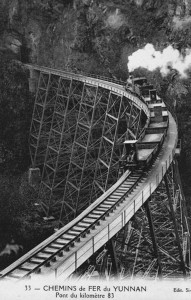

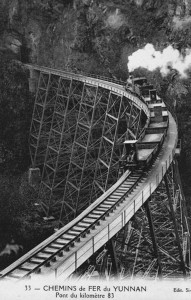

The pont en dentelles (“steel lace bridge”) at km 82 on the Lào Cai–Yunnan-fu line

The Yunnan Railway, finally, an extraordinary work, born of the imperial policy of a great nation such as ours, a masterpiece of the art of the engineer overcoming all difficulties. This also represents a tourist value of the highest order, as much by the impressive series of sites offered to the traveller all along this incredible railway line, as by the variety of countryside through which it passes, arriving after three days in the old Chinese city of Yunnan-Sen [Kunming], still mysterious, so full of character and curiosity.

Tourism organisation in Indochina

The current situation in the Far East, considered from the point of view which concerns us here, may be summed up thus: Indochina, however superior in its tourist attractions, finds itself excluded from the tourist movement in the presence of neighbouring countries which are inferior to her.

Hanoï could succeed quickly, at the price of a slight effort.

Angkor, already developed, may provide a model for the type of tourism organisation which should be established in places where the hospitality industry is not yet ready to meet needs.

As for means of transport, we certainly cannot yet claim perfection. However, tourist transportation exists here in such conditions that we can, with those in place at this hour and subject to some development of riverboat timetables, envisage the organisation of a comprehensive and quite satisfactory service.

Rocks in Hạ Long Bay

In short, the primordial elements have been created; one only has to develop them, to extend them and especially to co-ordinate them, in order to arrive at the receiving capacity of a given coefficient of tourists.

This brings me to consider what limit one can foresee to the development of the tourist sector.

It is a mistake, in fact, to suppose that, when it comes to developing a country from the point of view of tourism, the same type of programme will be of interest throughout the entire country.

Such an error is twofold; First, because most of the time the costs exceed the advantage presented. Then in most cases, the time limit does not allow visitors to devote the necessary time to visit all of a country’s different regions.

Most often, the modern tourist does not stay long: at each stage of his trip, he sees the sights quickly; he rarely assigns more than one day to the same attraction; and on the following day he goes to see something else.

The specialists who remain for a long time at some particular location are the exception and therefore have no place in the general question under discussion here.

Angkor Wat

From the above, the conclusion emerges by itself: It’s a question of determining the areas of Indochina for conversion to tourism.

They are distributed as follows:

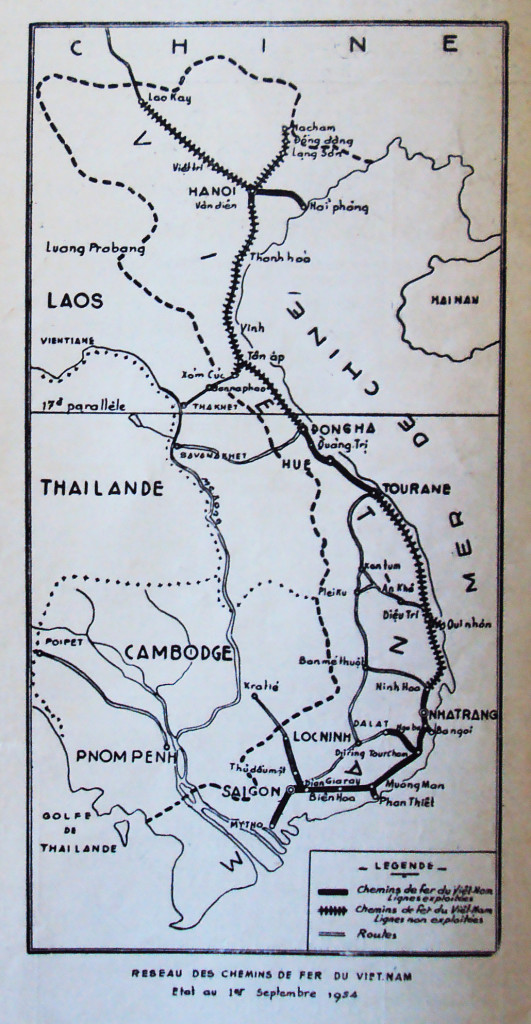

1. The Southern Region – 12 to 15 days

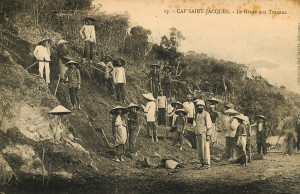

– A. Saigon and its environs; Cap Saint-Jacques, Trian Falls.

– B. Phnom Penh.

– C. Angkor and its surroundings.

2. The Central Region – 6 to 8 days

– A. Hue.

– B. The Tombs.

– C. Marble Mountains.

3. The Northern Region – 12 to 15 days

– A. Haïphong.

– B. Halong Bay.

– C. Hanoi.

– D. Yunnan Railway.

The Messageries-maritimes wharf in Singapore (Chocolat Félix-Potin)

So the complete journey through Indochina, made from one end to the other with planned connections so that there are no unnecessary stops, can be achieved in a period of 35 or 40 days. But this represents for most tourists a maximum availability of time.

To this period of time, we must also add the time required for crossings from Singapore to Saigon and from Haïphong to Hong Kong, an average of three to five days for each respectively.

Indochina, divided into three parts, does not offer equal interest from an intrinsically touristic perspective.

Indeed, one must admit that Saigon, located on the main Far East route, enjoying a renown as a pleasant stay and favoured by the fact of being the access point for Phnom Penh and Angkor, will be to a much greater extent the centre of attraction which a majority of tourists are content to visit, being unwilling or unable to venture further to the Centre and North of the colony.

Fort Bayard, Hạ Long Bay

The Northern region gets its power of attraction from two spectacular sights: Halong Bay and the scenery alongside the Yunnan railway. One will soon be able to reach it from Hong Kong more easily, as maritime services will shortly be reorganised to meet the requirements of special traffic in accordance with the overall aim of tourism development.

As for the Central region, only those tourists who wish to “do” Indochina are likely to visit.

This means that the effort involved will not be the same in each of the above three regions. Therefore I will examine these areas successively, from the point of view of both accommodation and communications.

Southern Indochina

Saigon, thanks largely to the enlightened action of the Comité d’Initiative Sud-indochinois (South Indochina Tourism Committee), is already, we can affirm, in a state to respond to an influx of tourists, especially since this influx will be gradual and at the outset will not exceed the current possibilities.

The Throne Room of the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh

In Phnom Penh, a considerable effort has already been made; however, the future of tourism in that city, contrary to what has quite inadvertently been done so far, will lie in developing the capital of Cambodia as a place where visitors stay en route from Saigon to the Angkor region, rather than as a destination in its own right.

In Angkor, finally, the bungalow established by the administration can satisfy every need, because it is designed according to the “pavilion system” which is applied without exception throughout Java.

This pavilion system consists of a central building which offers a range of common services – dining room, lounge, smoking room, etc – surrounded by chalets, all leaning against each other and each comprising one bedroom equipped with modern amenities and an adjoining shower room, plus a small covered terrace. This system has the overwhelming superiority of permitting the hospitality industry to extend its facilities economically, as and when the need arises, in contrast to building costly multi-storey hotel buildings as is generally done back home.

Detail from the wall of the central sanctuary of the Bayon temple

It is therefore fair to say, without pretending that we can achieve tomorrow what has been done in Java or even the Philippines, that in future South Indochina will be able to take a share of the already large number of visitors who arrive every year in the Far East; and that it is reasonable to work initially towards a figure of 1,000 visitors per season.

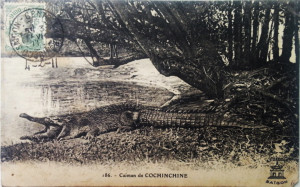

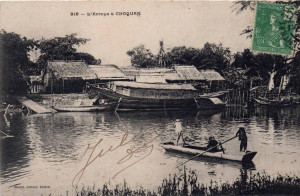

The means of communications in southern Indochina are very varied. Cochinchina and Cambodia are criss-crossed by a network of superb roads; the automobile is already represented there by more than 300 cars and by several public automobile services. River shipping services and railways may also, after a certain and easy development, respond easily to all the requirements of future tourist traffic.

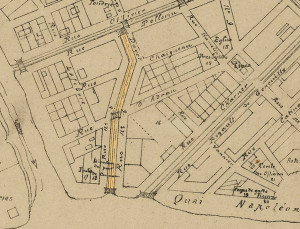

Saigon is already connected by rail to My-Tho, and as such is the starting point for all river services to Phnom Penh and Angkor.

With some minor modifications to the current mode of operation, the flourishing Messageries-fluviales de Cochinchine riverboat company will possess all the means to ensure a satisfactory service, in accordance with the operating conditions of international tourism.

A riverboat of the Messageries-fluviales company

The tourist clientele in Indochina has so far been insignificant. One might even ask the Messageries-fluviales to create its own special department for tourism.

At the moment, riverboat tourism is enjoyed only by a few individuals and isolated groups – interesting visitors, certainly, but not yet the large numbers which in future could bring substantial economic benefits.

Only when the tourist influx becomes large enough to become a “case apart,” thereby guaranteeing a sufficient and regular number of tourists each season, will the company consider the establishment of a special service adapted to this new clientele, as has been done in many other places, including in Egypt, where the prosperity of the river tourism business is well known.

At that point, the needs of the clientele go beyond the requirements of ordinary traffic, necessitating the intervention of the government, since this is a private industry exploiting a particular market. On the other hand, the government should not impose any pricing hardship on the company which is providing the services. It should be for the firm concerned to examine, like any other trader or industrialist, the tariffs it must apply to customers of whatever category who use its services.

The Messageries-fluviales wharf in Cần Thơ

The same goes for the operation of hotels and bungalows, which can be built either by private initiative, or by the administration for rental to the hotel industry.

To quote an example, the operation of the Angkor bungalow is entrusted to the Messageries-fluviales company, but this does not prevent administrative intervention to ensure the provision of special staff, equipment and draft or pack animals, all elements that are charged to the administration. Indeed, instead of the bungalow being granted free to the operator to exploit, the latter is limited in its exploitation by a tight list of charges.

Another example may be taken from the Tourism Organisation of Java, an absolutely perfect organisation which I will describe in detail later. The official agency of Batavia-Veltevreden gives all foreign visitors to the large Dutch colony a free set of documents which are so well prepared, so complete, and so carefully planned, that a trip throughout the whole island is the thing easiest in the world, even for the traveller less familiar with great excursions.

It’s by a set of processes which are perfectly within our reach in Indochina, that Java has given birth to and developed the huge tourist industry it enjoys today.

Takeo temple

It is important to clarify a key point here:

We are in the presence of an international clientele which is accustomed to pay throughout the Far East fixed prices, very much higher than those charged in Indochina for tourist trips, like Angkor for example. It is therefore important that, in order to create a sense of value in the eyes of the foreign customers, these same higher prices are applied to Indochina.

This would of course be to the benefit of the colony and in the interest of the operators of the tourism industry. It would be absolutely illogical and damaging to our reputation if the commercial exploitation of tourism in Indochina did not represent the same coefficient of expenses for the traveller and legitimate benefits for the country than in any other tourist regions of Asia.

The foregoing reveals a new issue which has not thus far been considered.

The Marble Mountains in Tourane (Đà Nẵng)

The season in which visitors can make an excursion to Angkor, the main attraction of South Indochina, is relatively short: it varies, depending on the year, but generally lasts from October to March.

The Compagnie des Messageries-fluviales has recently mapped the navigation conditions of the Great Lake. The review, we are assured, has shown that some minor works could, without overspending significantly, increase the duration of the season beyond the current length of six months. This observation, of considerable interest, deserves to be considered further.

Central Indochina

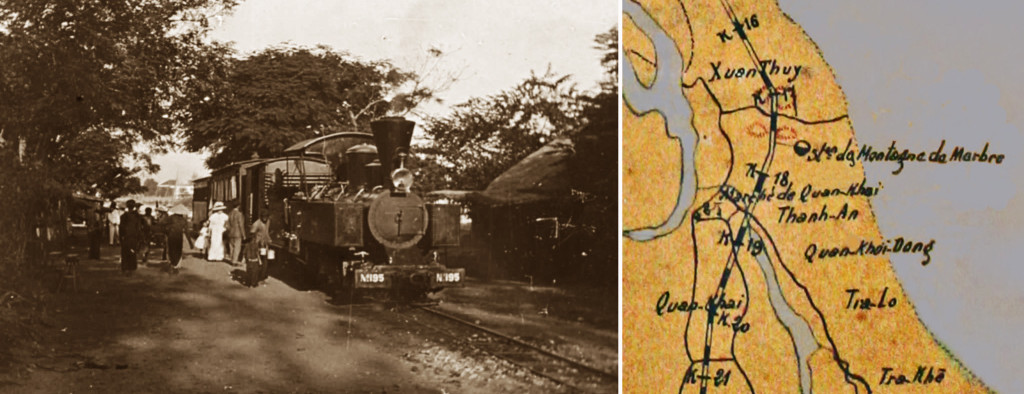

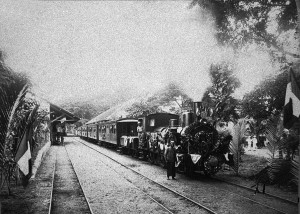

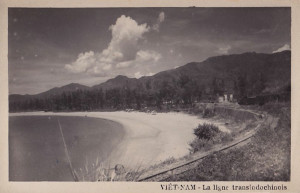

Tourane and Hue are linked by a railway line whose route is very picturesque.

On the other hand, there exists between Tourane and the Marble Mountains a small tramway which operates one train per day in each direction. This tramway can easily be used to access the Marble Mountains, which are located just a few hundred metres from one of its stations. The construction of an access road over a short distance currently obstructed by sand will be enough to make this wonderful excursion easier for visitors.

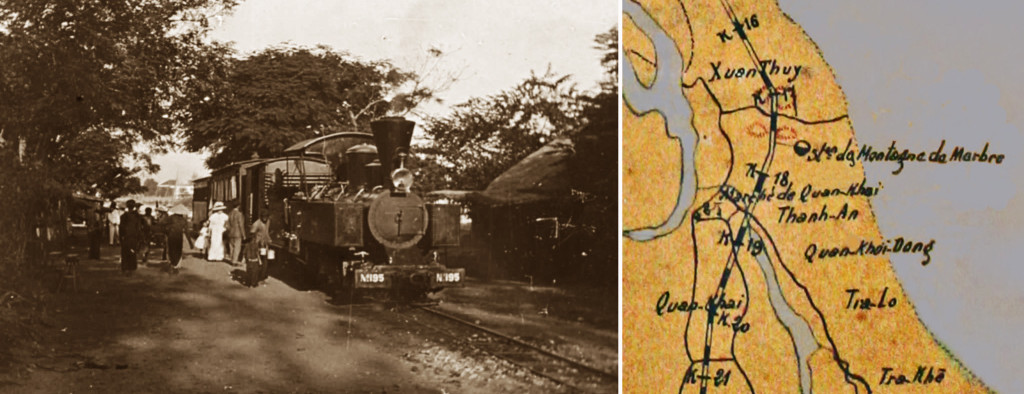

A steam tramway service waiting to depart from Tourane for Faifo/Hội An in 1906 (Fonds de l’Association des Amis du Vieux Hué), and a 1910 map showing the Marble Mountains tramway station between Tourane and Faifo

The Royal Tombs in Hue are accessible either by boat or by car. Good roads, passable by automobiles, connect many of them.

As for the hotel industry, this is perhaps sufficient, in Hue at least, for the current still very limited tourist numbers, but will need to be upgraded once tourism begins to develop.

It seems natural to consider, in this case, the possibility of administrative intervention, as previously mentioned.

Northern Indochina

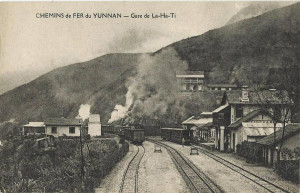

La-Ha-Ti station at km 70 on the Yunnan line

In the North, both Haïphong and Hanoï are already equipped with a hospitality industry which in future will be able to meet fully all the requirements of a large and “well paying” clientele.

Secondary but adequate hotels representing commendable private initiatives exist along the Yunnan railway at Lao-Kaï, Ami-Tcheou and Yunnan-Sen. Mobile buffets already operate on the trains.

Perhaps later, if tourist traffic justifies this addition, the Compagnie des chemins de fer de Yunnan may have to consider the introduction of sleeper carriages, like those used in India and America; the management told me that they were enthusiastic about this idea, which would make the five-day round trip from Haïphong to Yunnan-Sen and back much easier.

Regarding the visit to Halong Bay, the problem has been solved: the Frères Roque armaments firm now operates along the North Tonkin coast a world-class fleet of five steamships – the Emeraude, Perle, Saphir, Rubis and Onyx – all beautifully equipped and able to compete with any foreign ship of their class. Monsieur Roque is personally convinced of the value of the exploitation of Halong Bay. One finds in him a most absolute and most effective champion of tourism development.

Two of the five ships built by the Frères Roque to transport pasengers and cargo between Hải Phòng and Hạ Long Bay

Northern Indochina also has a Syndicat d’Initiative (Tourist Office). This organisation has not yet begun to operate fully, but it seems to have the necessary elements to play an important role in the tourism sector.

I spoke earlier of the prices that could be applied to international tourists: I will complete this observation by another which relates just as well to the hospitality industry as to transport. The established price must correspond with the provision of adequate facilities and comfort.

In other words, it is essential to build on what exists in neighbouring countries, in order to be neither superior nor inferior to what one encounters there, to provide customer satisfaction and to help give Indochina tourism an economic value of primary importance.

Maritime services

Maritime navigation services, as they normally function to or from Indochina, are represented by:

On board a Messageries-maritimes ship

A. – Compagnie des Messageries-maritimes

1. The “grand courrier” Far East line service from Marseille which stops at Saigon. This service, which operates every 14 days and continues on to China and Japan, should also stop at Tourane. The administration has already agreed that a Tourane stop would be useful and will impose this obligation on the company after the completion of the Vinh-Quan-Tri railway line. The plan is an excellent one, and we cannot but applaud.

The current stops are, from Marseille: Port-Saïd, Djibouti, Colombo, Singapore, Saïgon, Hong-Kong, Shanghaï, Kobe, Yokohama. Same stopovers on return.

2. The freighter which leaves Marseille on the 30th of every month and links Saigon with Haïphong and Tourane. Ports of call from Marseille: Port-Saïd, Suez, Colombo, Saigon, Tourane, Haïphong, Saïgon, Colombo, Djibouti, Suez, Port-Saïd, Marseille.

3. The coastal service which makes a series of intermediate stops between Saigon and Haïphong.

The Messageries-maritimes vessel André-Lebon arriving in Saigon

4. The Singapore-Saïgon service. This service operates every 14 days, alternating between a Messageries-maritimes “petit courrier” vessel and a British luxury cruise ship.

B. – Compagnie des Messageries-fluviales de Cochinchine

This company operates a twice-monthly Saigon-Bangkok service, in correspondence with the Messageries-maritimes “grand courrier” coming from France and continuing on to Japan.

C. – Compagnie des Chargeurs Réunis

This company operates a monthly service from Dunkerque, Le Havre, Pauillac, Marseille and Toulon (optional) to Saigon and Haïphong. Stopovers: Port-Saïd, Djibouti (optional), Colombo, Singapore, Saïgon, Tourane, Haïphong and back, except Djibouti. The Company is in talks with the state to make 13 journeys each year instead of 12.

The Chargeurs Réunis cargo vessel Ango

The services of the Messageries-maritimes are well known and many will be aware of the significant improvements made recently by the company, notably the arrival of its new and beautiful ships the André-Lebon, the Paul-Lécat and the Sphinx, whose dimensions and luxurious interiors have caused a sensation throughout the Far East.

It’s also worth mentioning the excellent “Euphrates” class cargo ships of the Messageries-maritimes, as well as the “Admiral” class vessels of the Chargeurs Réunis, which have recently supplemented with the arrival of the Ango, the Bougainville, the Champlain and the Dupleix, all built with the latest equipment and representing the last word in luxury.

Even the Messageries-maritimes vessels which operate the coastal services are worthy of note. I personally have travelled on several of these vessels, so I can speak knowingly and say, without claiming perfection, which is not very common here, that these ships in general may be compared very favourably with their foreign counterparts which serve ports like Singapore and Java – I have mentioned the activity of their traffic from the standpoint of tourism – and operate along the Malay coast.

The first class smoking lounge of the Messageries-maritimes vessel André-Lebon

As for the Haïphong-Hong-Kong, Saïgon-Singapore and Saïgon-Bangkok lines, an improvement is without doubt desirable if they are to participate fully in the development of a strong tourism industry.

To conclude this survey of the Indochinese maritime services, I believe that the planned restoration of the discontinued Singapore-Batavia line as part of a new service from Hong-Kong to Haïphong, Saïgon, Singapore and Batavia will make a significant contribution, not only to the development of tourism, but also to growth of the economy in general.

The commercial organisation of tourism

The vast tourist movement enjoyed by several countries in the Far East was not only created by each country alone. It was sparked, channelled and organised by a number of powerful companies which excel in this type of industry.

The best known of these foreign firms are Thomas Cook and Sons, Raymond and Whitcomb, H W Dunning and EMS Hall Tours Company of San Francisco, to name but a few.

A Raymond & Whitcomb tours poster

In France, some very honourable houses also specialise in long deluxe excursions, though unfortunately the extent of their operations so far cannot be compared to those of their competitors in other countries.

It is these companies which control the world tourism sector, a colossal movement, whose importance only those who have observed it at first hand in different parts of the world can appreciate. It is on these companies that we will in future depend to direct to Indochina each year an as yet undetermined, but certainly considerable, number of tourists.

Contrary to what may be supposed by people who are poorly informed about these matters, we should not be focusing on France as a potential tourist market for Indochina. French tourists who decide to visit our Asian possessions will always remain a small minority, and a factor of almost zero in any economic report, the only real issue here. Instead, we must look to the wider milieux from which thousands of visitors to India, the Far East and the East Indies are drawn every year.

The companies which control the movement of tourists and could channel more visitors in our direction have not so far considered our colony seriously for two reasons:

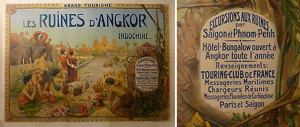

The Touring-Club de France Indo-Chine guidebook-album of 1913

The first is that they are unaware of its incomparable tourist beauty spots, simply because no serious publicity campaign has been launched overseas, apart from the efforts of the Touring-Club which were interrupted by the Great War.

The Touring-Club published a beautiful illustrated guidebook-album on Indochina. This 52-page publication, exquisitely designed, illustrated with numerous excellent photographs and incorporating both French and English text, was a work of which our great association should be very proud.

However, that publication represented more than just a guidebook: It was almost a luxury item, certainly far superior to anything published elsewhere in its genre.

Ultimately, that very superiority proved to be a drawback: the Touring-Club Indochina album-guide was large, luxurious and expensive, when a less elaborate publication would have done the job just as well.

A page from the Touring-Club de France Indo-Chine guidebook-album of 1913

There is a very good way to persuade these firms to channel tourists to Indochina, and that is to invite them to send their agents on study tours which we will arrange for them in each of our three tourist regions.

After such study tours, we can be certain that the agents will return to their countries with the conviction that Indochina is an unrivalled destination ideally suited to those of their clients who have already travelled widely and are looking for something special, something different.

Moreover, these agents will be better qualified than anyone to establish points of comparison with other tourist countries of the East, the Far East and the East Indies; it is they who will formulate a general tourism management programme, placing Indochina at the level of other countries regularly frequented by their clientele.

It is also they who will control, subject to the implementation of such a programme, the number of tourists who can be sent each year to Indochina.

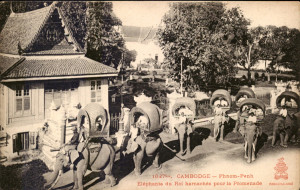

The King’s elephants on parade in Phnom Penh

In effect, the clientele of these powerful companies is, if I may use the expression, a true “market” of which the potential returns are known.

It’s thus by adopting a set of measures in agreement with the tourism providers that we can prepare the three regions of our colony, exploitable in the vein that we are studying here, to receive an expected number of new visitors.

These firms are also the commercial enterprises which, based on the current conditions of transport and hospitality, or by requesting certain changes that would improve the existing elements, will identify the tour packages which must be developed as new items for the tourist market. The firms will then sell these tour packages just as they currently sell tours to Japan, the Far East, or the Archipelago of East Indies. They have not done this so far with Indochina for the reasons that I have sought to determine above with the most precision and clarity as possible.

It would be desirable for the French tourism industry also to be involved in the study tours, which may be easily organised on site by an easy path to be deducted by the data above.

Another view of Angkor Wat

I have, understandably, some reluctance to speculate in advance what number of visitors we can hope for at the outset.

However, we already have a figure for the total number of tourists who currently travel near to Indochina and pass before its ports, without setting foot in it.

In the Far East, India, the East Indies, Java and the Philippines, we may find, as I said at the beginning of this work, a total of approximately 57,000 visitors each year. This clientele, formidable as it is, does not need to be enticed to the Far East: it’s already here. It is therefore a potential market in the region, waiting to be tapped. And if these visitors have not so far been brought to our East Asian Empire, it is, I repeat, due to the fact that no attempt has yet been made to publicise it, despite the fact that we are well aware of the considerable potential income they represent.

Would it be an exaggeration to predict that, out of so many thousands of free travellers, all eager to experience new artistic or natural wonders, we might from the outset attract a figure of 1,000 tourists per season?

The courtyard in front of King Tự Đức’s Tomb in Huế

I do not think that this is a utopian idea. And such a result would be considerable, when one considers the rapid growth of tourist which, by simple and inexpensive means, has been achieved in Java, a place relatively close to our Indochina yet significantly less endowed in major attractions.

And what opportunities will tourism offer to our indigenous arts and industries, which we so commendably seek to develop through other means? The arrival of foreign tourists could bring substantial profits to local businesses which currently serve only the needs of the sedentary population!

Here again, tourism must be seen as an economic element of primary importance, and one can only be surprised that it has not attracted more attention from us before now.

The coming of “grand tourisme” in Indochina will also have another consequence which should not be overlooked: it will encourage the conservation of sites like Halong Bay, that natural wonder which imprudent concessions have blighted with mines and quarries.

Khone Waterfalls in Laos

Furthermore, by involving the Sites and Monuments Committee of the Touring-Club in the development of heritage tourism, we may nurture respect for, and guarantee the preservation and restoration of, the architectural splendour contained in our Asian territories, thus giving to our subjects evidence of our concern and our respect for their history and religious traditions, to which they themselves attach so much importance.

In this form, no one could deny how tourism could benefit Indochina.

Publicity

I conclude this study on a rather mundane, but highly important subject: publicity.

This is indeed a crucial point. All of the countries which have made the exploitation of tourism a major economic objective have adopted a uniform mode of publicity which may be broken down into three parts:

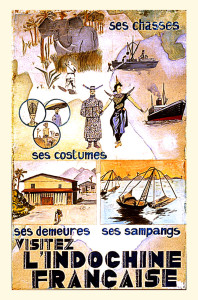

A poster promoting excursions to the temples of Angkor

1. Posters

2. Brochures

I will speak only of the latter, since the role of the first defines itself.

These must be of the model adopted by foreign tourist organisations worldwide: cheap booklets; easy to put in your pocket; reduced text; some photographs and precise information on hotels, transportation and prices, as I mentioned earlier.

This type of publication is common in Japan, America, Java, the Philippines, India and Malaysia.

It must be constantly offered to the public, and distributed in all crowded public places, including halls of travel agencies, hotels, banks and shipping companies.

A later “Visit Indochina” poster

The permanence of this publicity is assured by a correspondent on the spot in each of the centres of interest, that is to say, in the great capitals of Europe and America: Colombo, Singapore, Batavia, Hong-Kong, Shanghai, Yokohama, Tokyo, San Francisco, Seattle-Tacoma and Vancouver.

3. Local publicity

This will be provided on site by the tourist offices:

a) Permanent tourist information offices must be set up in all of the main centres; at the present time they exist only in Saigon and Hanoi.

b) Local publicity will be provided in brochures, each focusing on different regions, as happily has already been done for some Indochina destinations.

Conclusion

Equipping Indochina to receive its share of the tourism which has hitherto by-passed it will, of course, incur a few expenses.

But if tourism is of general economic interest, it also represents a whole array of special interests.

So it is therefore the public authorities on one hand, and the interested parties on the other, which must bear the expense of developing it.

Colonial Batavia (Jakarta)

We can learn much from the way in which tourism programmes have been designed in Java, where one can find a very active tourism promotion agency.

The Dutch administration has established a Central Office for Tourism, with official government status.

For Indochina, it would be preferable, given the results it has already obtained, and the invaluable services it has already rendered, for the functions of a tourism promotion agency to be delegated to the Touring-Club. It could then set up a Tourism Office which, in constant communication with metropolitan agencies, as well as foreign tourism agencies, would take charge of both internal organisation and external programmes.

The cost of running such an office is likely to be no more than 50,000-60,000 francs per annum, based on the figures kindly provided to me in Batavia by the very distinguished director of the Netherlands Office. There, half of the running costs are provided by the shipping companies and railways, the hotel industry and other trade groups which benefit from tourism. The government then matches the funds gathered by these private initiatives.

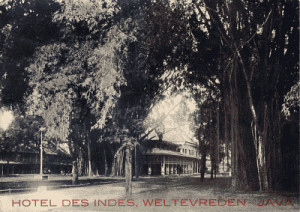

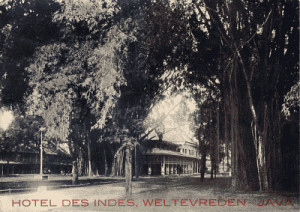

The Hotel des Indes, Batavia (Jakarta)

It is thanks to this system, and to the perfection of its organisation, that Java succeeded in increasing its number of tourist arrivals from 500 in the year before the war to the current figure of 8,000 per annum.

I will synthesise the results obtained from the Dutch colony by mentioning just these two examples which were selected from over one hundred:

Dutch ships serving Java are crowded to the point that seats are very hard to get, so when I came back from Batavia to Singapore, I had to rent an officer’s cabin, which is also a practice allowed on these boats.

And at the Hôtel des Indes at Batavia-Veltevreden, which five years ago was an establishment of secondary order, certainly much inferior to the main hotels in the two major cities of Indochina, has recently executed a two million dollar expansion programme …

One may take all this case as a moral tale and learn from it.

I will finish by pointing out that the Indochina administration regards the development of tourism as a great issue on which depends the prosperity and future of our great Asian colony.

Another view of Angkor Wat

Several years ago, the Governor of Cochinchina and the Residents-superior of Annam, Cambodia, Laos and Tonkin made known to the president of the Touring-Club Committee, the late M Guillain, former Minister of Colonies, their approval of the terms of a report which had been presented to them on the organisation of tourism in Indochina. Similar communication was made to the Ministry of Colonies.

As for the positive feelings of the Governor General, M Albert Sarraut himself took the time to express in happy terms his support for tourism development in an address delivered to the meeting of the government council in Hue in 1913.

The acquiescence and the unanimous support of public authorities are now established and will remain for the future: it is a fact whose significance cannot be diminished.

Well combined and wisely co-ordinated, it is hoped that this bundle of efforts and goodwill will have the effect of finally endowing our East Asian Empire with the prosperity which can result from the organisation of large-scale international tourism.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.