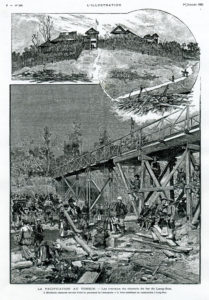

The inauguration of the completed 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line in December 1894

Opened in 1894, the first railway line in northern Việt Nam was a military line connecting Phủ Lạng Thương (Bắc Giang) with the border post of Lạng Sơn. A costly failure, the line was upgraded in 1899-1902 and transformed into today’s 1m gauge Hà Nội-Đồng Đăng line – but not before French aristocrat Henri-Philippe Marie d’Orléans had laid into the authorities for the gross incompetence surrounding its construction and the unsuitability of its rolling stock.

The main street through Đáp Cầu, a town on the Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn (later Hà Nội-Đồng Đăng) line

I was recently invited to the inauguration of our new national road from Hanoi to Hai-Duong; it starts on the left bank of the Red River, a little above Hanoi. Only just completed, this road is excellent, though it has not yet been subjected to the test of the summer rains. The region it traverses is currently full of barren swamps, but over the next year these will be replaced by fertile rice paddies. Such results have already been achieved between Phu-Lang-Thuong and Kep.

In military terms, new roads like this benefit our troops more than they do the pirates and brigands of the far north, indeed, the latter prefer to see our settlements remain isolated from each other. The old narrow paths, known only to local people, are very difficult to access, and serve those who wage guerilla war against us. On our wide new highways, it’s possible to move easily in more than just single file, and under these new conditions our enemies lose much of their advantage.

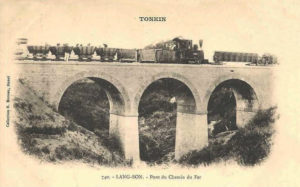

A bridge on the 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line

In the same way, the new Tien-Yen-Lang-Son road, which I believe has also just been completed, crosses the eastern region of the country parallel to the open border with China, and will undoubtedly be of great strategic importance.

This new system of 11m wide highways, also capable in future of accommodating tramways, certainly represents progress, but it’s not perfection. Railways would be preferable, and the example given by the English in their colonies should serve to guide us. Upper Burma was taken by the English in 1885; by 1887, a railway had reached Mandalay. Despite the competition of easy navigation along the Irrawaddy River, that line has since proved more successful than any of the East Indian Railways.

Here in Tonkin, just one proper railway line – the line between Hong Hai [Hòn Gai] and Kebao being simply a mining tramway – has so far been built, linking Phu-Lang-Thuong with Lang-Son near the Chinese border.

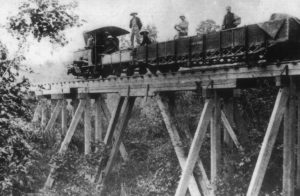

A works train hauled by one of the line’s 5-tonne Decauville 0-4-0T locomotives, pictured during construction of the 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line

We should therefore examine its strategic and commercial importance. Far be it for me to discuss in detail the construction process; I don’t want to name or attribute blame to anyone in particular, yet it is good for the public to know how this enterprise of general interest was entered into and conducted. A few facts will therefore be exposed, for common sense to judge.

The construction of the line was granted to a M. Soupe, who later passed it to sub-contractors.

According to the tendering specifications, the administration reserved the right to purchase the rolling stock, and also paid directly for the construction of bridges. But they preferred to engage an expensive contractor, and, as a result, to pay under the terms of his contract, a commission of 18%, amounting to 300,000 Francs which could otherwise have been saved.

Plenty of warnings were given to the administration, flagging up how detrimental this was to the state, but no one seemed to take any notice.

Kép station on the 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn (later Hà Nội-Đồng Đăng) line, pictured in 1893

Written instructions by the Under Secretary of State were often contradictory and caused the greatest embarrassment to our engineers in Tonkin.

The means of purchase being known, we should also consider the type and quality of rolling stock, and above all the decision to adopt a track gauge of 0.6m. A Dutch engineer, who I met while travelling, expressed surprise that the French had chosen this gauge. “Neither in the English colonies, nor at home,” he told me, “do they use a gauge of less than 1m. Above all, where a line covers distances of more than 100km, as this one does, 0.6m gauge equipment will wear out very quickly and must be constantly renewed. Furthermore, the route of this line travels through mountainous country, and with gradients of up to 30mm/m, Decauville locomotives can hardly haul convoys of more than three wagons. The more practical 1m gauge has already been used in Tonkin by a private company for the coal operations of Hong-Hai, where only a small distance is covered; all the more reason, it seems, to select the larger gauge for longer journeys. ”

Two of the line’s three Decauville 0-4-0T locomotives (No. 62 “Langson” and No. 80 “Haiphong”) were displayed at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris before being shipped to Indochina. This photo depicts a Decauville 0-4-0+0-4-0 Mallet at the Exposition

As for the quality of the rolling stock, they sent to Phu-Lang-Thuong some of the rolling stock which had been displayed at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris; I myself saw one of the locomotives and several carriages. Had the latter even been in perfect condition, which I think is not always the case, we could still reproach them for being entirely unsuitable for use in hot countries.

During the enquiry into the Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang-Son railway line, which took place on 27 November 1890 at the Chambre des députés, the Deputy Secretary of State said that he had been pushed to commence work on the line without consulting the Chambre by a “superior interest,” namely that of supplying troops to, and transporting sick soldiers back from, a remote military outpost.

However, on this last point, an objection may be made. The wagons purchased were entirely unsuitable for hot countries; no modifications were made to the French-built rolling stock in order to counter the dangers of sunstroke. For the countries of the East, one does not build as for Europe, and on this subject I refer the reader once again to the example of our neighbours, the English.

“The wagons purchased were entirely unsuitable for hot countries; no modifications were made to the French-built rolling stock in order to counter the dangers of sunstroke”

So, to justify the preference given to Decauville over other railway manufacturers, it is difficult to invoke strategic and military interests; transportation in Decauville rolling stock will be slow in highlands and, in the hot season, dangerous for troops.

Let us now leave aside the criticism that can be directed to the adoption of the 0.6m track gauge and the choice of rolling stock to focus on the operation of the line.

In November 1890, it was announced that “Part of the line will be in operation by early 1891 and the entire line will be functioning by the end of that year.”

Here we are in 1893; the government forecasts were incorrect.

Was the line mapped properly?

Construction of the 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line

The tender specification states: “Before the works commence, the route will be mapped by state engineers; the contractor will assist in this operation.”

I believe that a preliminary route was mapped, but due to the difficult security situation in that area, the landmarks and marker posts were repeatedly destroyed. In addition, the route was originally mapped for a track gauge of 1m, and was not therefore suitable for a line of 0.6m gauge. As for the entrepreneur, he demanded the implementation of the initial route, purely in order to give him more work.

Besides this, the representative of the contractor M. Soupe did not appear to have the necessary expertise for the establishment and management of railway construction sites, so the state engineer offered his assistance, and work was begun with the help of his staff. But the contractor’s Paris office disapproved of this situation and secured the dismissal from the project of the state engineer, M. Lion. He has recently returned to Tonkin to work as consulting engineer for M. de Lanessan.

Construction of the 0.6m gauge Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line

After the departure of M. Lion, significant concessions were made to the contractor.

He was permitted to rebuild completely, under the pretext of poor mapping at the commencement of the line, 3km of the 18km already in existence. Cost – 30,000-40,000 piastres on top of the existing budget.

On the section of line west of Bac-Le, instead of paying the workers according to working hours (with upward adjustment of wages to reflect the increase received by the company), the contractor was allowed to institute a system of infrequent payments to its workers. Then, beyond Bac-Le, it began to pay workmen per cubic metre of earthwork. This new system, disadvantageous to the state, permitted the contractors to sub-contract the work.

The first mode of payment would have been preferable, had its application had been applied strictly; but the local workers were paid by the company at the rate of 15 cents per head, the latter alleging that it also provided them with clothes and food, and then falsely accounting to the state a wage of 30 cents per head. This was duly reported by whom it may concern; then everyone moved on.

Between 1890 and 1895, eight 9.5-tonne Decauville 0-4-4-0 “Mallet” patent compound jointed locomotives were purchased for the line – No. 83 “Eugène Étienne,” No. 84 “Phu-Lang-Thuong,” No. 85 “Commandant Rivière,” No. 86 “Carnot,” No. 126 “Commandant de Lagrée,” No. 188 “Kinh Luoc,” No. 195 “Francis Garnier” and No 209 “Paul-Bert.”

When they arrived at an insurmountable obstacle, the construction team simply gave up and restarted elsewhere. East of Bac-Le, no fewer than six different track plans were adopted, one after the other; the last earthworks having been washed away, they simply embarked on another.

Besides, how may one believe in the good direction of an enterprise when it passes so often into different hands? Disclosure of reports is very instructive for those of us who have colonial questions at heart, showing how the interests of the state are taken into account by the authorities which have the primary mission of defending them.

It is not only in the work of mapping this line that we encounter culpable negligence. The operation of train services from Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang-Son was initially granted for a period of two years to an entrepreneur with a guarantee of 3.60 Francs per tonne per kilometre, but after two years it was seen that the concessionnaire had won greatly, so the line was placed out to tender again and someone else acquired the franchise for just 1.20 Francs per tonne per kilometre. Difference: about 345,000 Francs that the state should have been able to save.

The 1m-gauge Port-Courbet (Hòn Gai)–Hà Tu mining tramway in Tonkin, built after 1888 by the Société de charbonnages de Hon-gay

I am now told that, thanks to the intervention of the Governor-General, work to upgrade the 0.6m gauge line to 1m gauge is finally underway. I hope so, better late than never.

When M. de Lanessan visited the mines of Hong-Hai, he marvelled at how cheaply the laying of 1m track could be achieved by a private company for its own operations, with an eye to economy. Between Phu-Lang-Thuong and Lang-Son, the interest of the state was at stake, yet the line was seen as a cash cow to be milked at pleasure, forgetting that the milk was that of France, and there will come a time when it will no longer be provided.

In summary, the construction of the Phu-Lang-Thuong-Lang-Son railway line, estimated initially to cost 4 million Francs, has already cost us more than 8 million, and if, on completion, it costs less than 12 million, we will consider ourselves lucky. In the space of two years, on flat terrain and without great physical difficulty, barely half of the line has been built – that’s not even 40 kilometres in a straight line! Meanwhile, during the same period, in rugged and difficult country, the English have laid nearly 200 kilometres of 1m gauge track.

These are results which are painful to see, yet I feel it is my duty to speak out. Let us take stock of the situation and we will find, if we want, that the situation is easily remedied.

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.