Emperor Thành Thái in court costume

M. Rousseau, Governor-General of Indo-China, is on his way to France.

We know that he was recently elected as a senator of Finistère. And since, on the eve of his departure from Tonkin, he went to visit the king of Annam in Hue, the rumour has circulated that this was a farewell visit, and that Rousseau would not return to his post. However, this news has now been overturned. It is now asserted that M. Rousseau has not been dismissed of his functions as governor-general of Indo-China.

His visit to the king of Annam was therefore a simple visit of politeness, on the eve of an absence of several months.

There is much talk at this moment of the sovereigns of our various colonial possessions.

The queen of Madagascar has naturally for several months deserved the honours of our chronicles. Now, the sons of King Toffa, one of the most powerful chiefs of Dahomey, are our guests in Paris. Before any attention was paid to them, there had been much discussion about another king of Dahomey, our opponent Behanzin, who is at present imprisoned at Fort-de-France. There is even a story going round that the prisoner of Fort-de-France is actually a fake Behanzin, but the most authoritative testimony has now put paid to this legend – it is without doubt the true Behanzin whom our troops captured after the taking of Abomey.

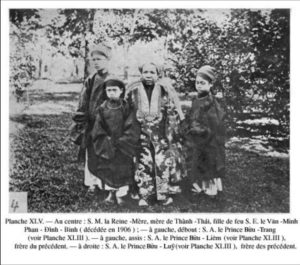

Emperor Thành Thái and his three brothers, with his interpreter and French personal attache (Le Monde Illustre, 12 November 1898)

After all these African monarchs, why should an Asian monarch not be the order of the day? Thanh-Thai, king of Annam, also deserves to be spoken of. The visit which M. Rousseau has just paid to him gives us an opportunity to do so. He is scarcely 16 years old, this little king of Annam, and has reigned since 1889. His existence has hitherto been very tranquil, and there is no proof that it will not continue to be so. The same could not be said about his direct predecessors, for in less than a few months, several of these sovereigns disappeared in a tragic way, in the prime of life.

One of them, Duc-Duc, who was very devoted to us, reigned for only four days; he was killed at the instigation of his regents on 21 July 1883. His successor was Hiep-Hoa, who was forced to take a poisoned beverage after six months. Kien-Phuc had been on the throne for only a short time before he, too, became a victim of assassination.

There was also another king of Annam, whose reign was equally ephemeral. This one was called Ham-Nghi. He was supported by regents who were hostile to French influence. When these fierce mandarins were taken prisoner by our soldiers, Ham-Nghi, who had fled with them, remained a cause of division in Annam. He still had partisans who believed in his return to power; it was therefore decided to exile him far from Annam, so he was conducted to Algeria, where he remains still, and where, faithfully enlightened as to the lamentable fate of the rebellious Annamite sovereign, he has accepted his lot and now lives peacefully, without any monarchical ambition.

Yet Thanh-Thai is perhaps less fortunate than he. It is true that, now that French influence is completely established, he no longer fears poison or the dagger. But while Ham-Nghi is now free in his movements, even to the extent that he was recently able to visit France, Thanh-Thai passes cruelly monotonous days behind the ramparts of the palace of Hue, where he is confined.

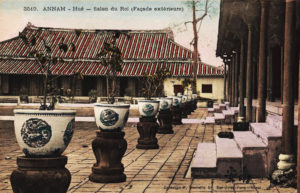

Inside the Purple Forbidden City

In his Tour d’Asie, M. Marcel Monnier, who passed through the Annamite capital in May of last year, describes this palace. “The light,” says he, “penetrates from above, as if into a prison courtyard, reverberating on the flagstones, a blinding and crude light which accentuates the despairing sadness of that royal residence where silence reigns. Here, the calm has a je ne sais quoi of menace. We can only guess how many intrigues, how many cruel dramas were slowly prepared in recent years under the cover of this deceitful peace. Nevertheless, it must not be supposed that the palace of Thanh-Thai is a residence without grandeur; it occupies a considerable area and consists of constructions of many kinds, palaces and pavilions.

On certain days, solemn ceremonies take place. So it seems that Asiatic life is resuming its rights in the vast enclosure. Mandarins of all ranks, in tight formation, bow down before their master, who, diminished but not fallen, remains for them the living symbol of nationality.

There are several large halls, that of the throne and that of audiences, with heavy pillars covered with red and gold lacquer, and that of the ministers’ council, where, at dawn, between 5am and 6am, the regents come to await the moment to make their daily appearance before the king. The royal palace itself is closed to all, guarded day and night. Further on, no less well guarded, are the harem and the apartments of the three queen-mothers.

There are currently no less than three queen-mothers in Hue. “They live a life of seclusion,” says M. Marcel Monnier, “turned into idols and fetishes, and the king himself may only appear before them barefooted, he may only speak to them on his knees.” One is the mother of Tu-Duc, the king of Annam at the time of the French conquest, who is 87 years old and blind. The second is Tu-Duc’s widow, now 70 years old. The third, the mother of the current king, has just reached her 40th year, and the few people who have seen her taking promenades, when the wind spreads the curtains of her golden palanquin, say that she is very graceful, almost beautiful.

The Queen Mother Empress Từ Minh, mother of Thành Thái (BAVH 39, 4)

However, it seems that they are not always tender towards the little king, these three queen-mothers.

Hidden behind a veil of silk, in the midst of their courtiers, they allow him to approach them only after long reverences, during which he pronounces several times the single word “con,” which means “child.” It is only after he has prostrated himself nine times with his forehead against the ground that the curtain is pulled back. And then, still on his knees, he must listen to their orders and remonstrances.

This posture is a bit humiliating for a king. It is true that the power of this one is very precarious. But if the young sovereign deserves a reprimand, that’s not the only humiliation he must endure – one of the serving women comes to him, carrying on a tray a cane made of rattan, a symbol of punishment. It is almost like the European martinet, reserved for mutinous children. M. Marcel Monnier informs us that one day, Thanh-Thai tried to revolt against the use of the cane, seizing and breaking it. But the correction which followed was such that, since then, the little king no longer has the slightest inclination to rebellion.

The apartment of Thanh-Thai is separated from the harem by a series of pools large enough for women to bathe in. The latter go to their lord and master only when he asks for them. Their names are inscribed on plates of jade, and the king indicates which one he chooses by turning over the plate. His servants then hurry to seek the chosen one.

At 5am each day, Thanh-Thai is already up. He is dressed by ladies of the royal wardrobe. After a light breakfast, he goes to his study room, where his teachers await him. After a few hours of study, cut off from others, followed by an interview with his ministers, he has another meal. From 10am to 12 noon he retires to his apartments. At noon, lessons resume. The king learns French and speaks it well enough. At about 4pm, he takes physical exercise in the gardens. Then to dinner, where a European dish is served. By 8pm his majesty is in bed.

Such is the daily existence of this 16-year-old sovereign.

Emperor Thành Thái

At times he does not hide his annoyance. He also anxiously awaits the four or five annual ceremonies over which he must preside – the Feast of the Spring, the Feast of the Harvest, the visit to the Tombs of the Kings, etc – during which he gets the chance to leave the palace. Along the avenues he processes, past incense burners and through rows of altars loaded with flowers and fruit, followed by mandarins in superb silk tunics and escorted by guards dressed in red and wearing lacquered hats. On the route he sees not a single inhabitant, for to go outside during the passage of the king and stare at him would be tantamount to an insult. The procession proceeds to the river, where a richly decorated junk awaits the king. Forty oars row him for about an hour. And all the time the boat is followed by skilful swimmers who swim alongside in relays, ready to catch the little monarch in the event that the boat capsizes.

M. Marcel Monnier, who met Thanh-Thai during a visit to the French Resident in Hue, describes him in a long robe of golden cloth studded with precious stones. He speaks little, and when he does speak, it is above all to ask questions.

On that day, he enjoyed the snack which was served, and even drank several glasses of champagne, while his two brothers, standing behind him and all dressed in green like small parakeets, ate cakes and sweets.

France has, to some measure, instituted in Indo-China the system of the British in India. While assuming the direction of the government and ensuring our full influence, we have not infringed on national traditions.

In India, the rajahs who submitted to the British crown still guard their thrones and their ancient prestige, which are like a facade concealing foreign domination. Likewise, the king of Annam, considered by his people less as a leader than as the representative of traditions and rites, preserves in the eyes of his subjects all the authority of his ancestors.

We must not think of suppressing at one stroke such centuries-old customs, of destroying the traditions of a country which we wish to pacify.

Mandarins in front of the Thái Hòa Palace

We have applied this same system to Cambodia, and many would like it to be so in Madagascar, where Queen Ranavalo will be kept on the throne. Others are in favour of annexation, pure and simple.

But whatever type of regime is ultimately decided upon, protectorate or annexation, we may trust that we will not lose the benefit of our efforts, and that so many sacrifices of men and money will not be in vain.

Jean Frollo

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.